(This article was prepared within the framework of KHAR Center’s research on Azerbaijani authoritarianism)

✍️ Elman Fattah – Head of the KHAR Center

Author of “New Authoritarianism and Azerbaijan” and numerous articles on post-Soviet authoritarianism and international relations.

Introduction

There is a mistaken belief in Azerbaijani public opinion that the Aliyev regime has somehow built an individualized repressive system and, compared to similar regimes, is more resilient—hence its long endurance. In reality, Azerbaijan’s current repressive regime is neither as unique nor as “exceptional” as it is often portrayed. It represents a local manifestation of a universal authoritarian trend that has repeatedly emerged over the past century—from Latin America to the Middle East, from Eastern Europe to post-Soviet regions.

Such rigid regimes typically crystallize around the resolution of a long-standing and painful national issue. The leader who resolves that issue assumes the role of a savior and accumulates substantial political capital through the legitimacy derived from that achievement. In the subsequent phase, this tendency gradually intensifies: political competition is curtailed at the outset, and eventually the political system closes altogether.

The victory achieved in the 2020 war likewise served as a psychological and ideological turning point that reshaped the political dynamics of Ilham Aliyev’s rule. Contrary to naïve expectations, the atmosphere of national unity that emerged during the war did not steer the authorities toward reforms after the victory; instead, it elevated the regime to a status of “untouchability.” Victory made the regime even less tolerant of criticism and political alternatives.

Thus, the post-war period did not open opportunities for democratic development; on the contrary, it further accelerated hard authoritarianization. In this way, Azerbaijan’s political system slid onto a well-trodden global path of “post-national-success dictatorship.”

This analysis seeks to answer the following core question:

How did the success achieved in the 2020 war accelerate Azerbaijan’s transition from authoritarian governance to dictatorship, and through which institutional, psychological, and ideological mechanisms is this transformation taking place?

The aim of the article is to analytically examine how narratives such as the post-victory “savior” image, “security,” and a “debt-bound society” are steering Azerbaijan’s political system in a particular direction.

The Reactivation of the Savior Myth

The “savior” image in Azerbaijani political thought is an archetype with deep historical and psychological roots. Its modern version began to take shape around Heydar Aliyev from 1993 onward. At that time, the narrative was clear and purpose-driven: a transition from crisis to stability, from chaos to state order, from separatism to centralization. In other words, the savior myth primarily carried an institutional character (Arif Guliyev, 2024). The state was, in effect, newly forming; governance was being restored; and the legitimacy of centralized authority was presented as a response to the risk of separatism. Put differently, this myth overlapped with a concrete historical situation and was able to organically connect with the existential fears felt by society.

However, from 2020 onward, this archetype re-emerged with new content. This time, there was no fear of state collapse or chaos. That is precisely the difference: whereas in the earlier period the savior myth served the creation of the state, it now aims to emphasize the sanctity of the savior himself. The state is no longer being built; instead, the head of state is declared untouchable and sacred, while “security” is transformed into a taboo that forbids all political and public debate. As a result, the savior myth transitions from an institutional phase to an ideological one, and the leader becomes identified with the state itself.

From Victory Legitimacy to Dictatorship

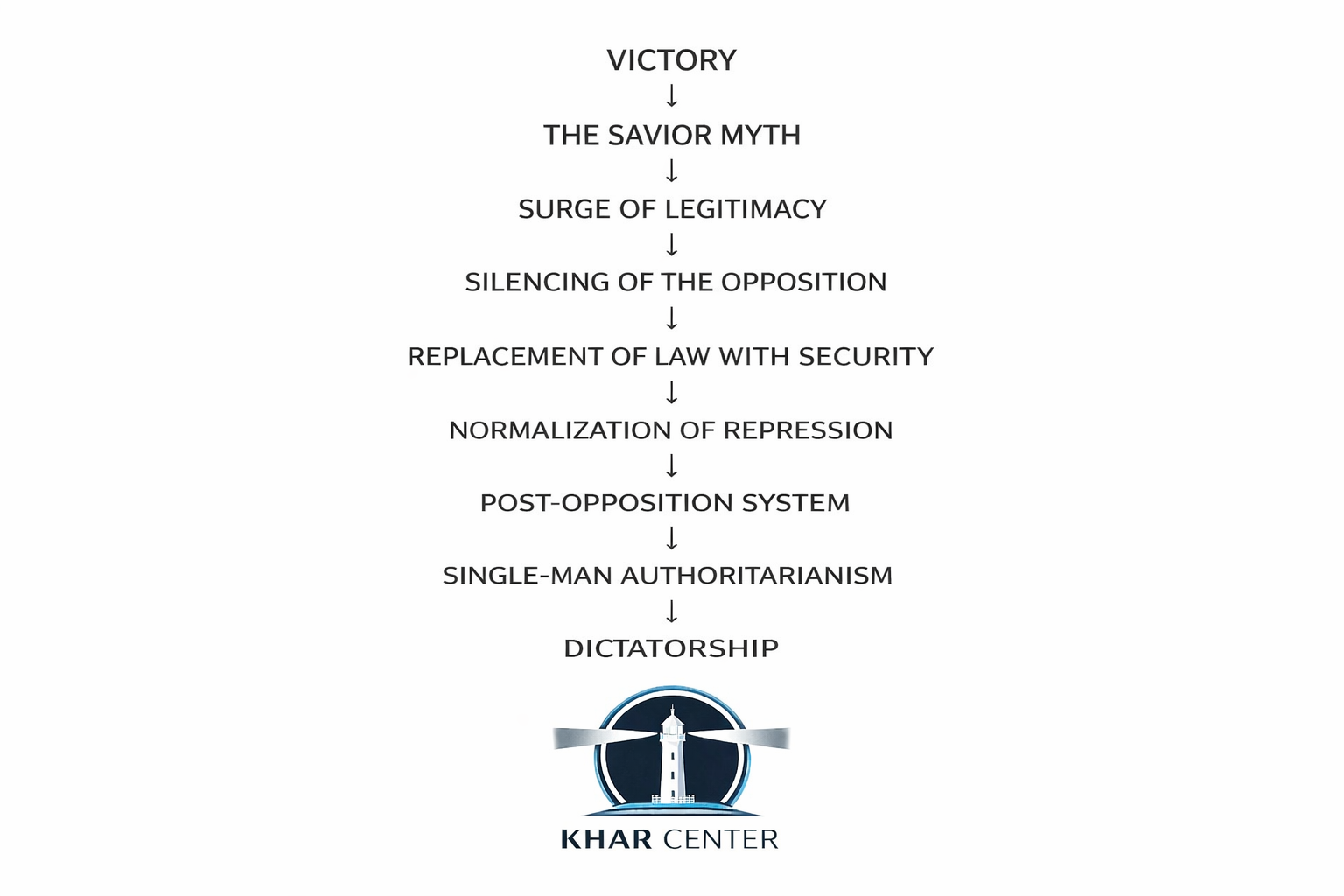

Military victories most often result in the erosion of political freedoms. The “savior” narrative that emerges after victory leads to the silencing of opponents, the replacement of the concept of law with that of security, and the transformation of repression into the principal method of governance. As a result, the system first moves toward personalist authoritarianism and then advances toward dictatorship (Neta C. Crawford, Catherine Lutz, 2025).

This diagram illustrates how authoritarianism in Azerbaijan has gradually consolidated after the victory.

Victory generates emotional euphoria in any society. The Azerbaijani authorities also capitalized on this opportunity, accumulating significant political capital through the image of the “savior.” As a result, thanks to this electoral legitimacy, the regime now presents the opposition as a “threat to national interests,” law is sacrificed to the concept of security, and punishment and fear are transformed into the primary tools of governance.

It was precisely from 2020 onward that the political space in Azerbaijan began to narrow sharply. The wave of repression that started in the autumn of 2023 intensified further in 2024 and 2025 (Giorgi Gogia, 2025). Independent media and civil society activity inside the country have been effectively banned. The very existence of the opposition has become questionable. This represents a typical example of the transition from classical authoritarian governance to a post-war system of total control.

“First it gives, then it makes you pay dearly”

This mechanism is one of the most effective methods of legitimization in authoritarian governance. In essence, it is simple, yet psychologically extremely powerful: the authorities remove a historical and emotional burden that society has carried for years, and in return reclaim political freedoms. In Azerbaijan, this burden was the trauma of occupation, and by eliminating this trauma through the 2020 war, the regime abolished all political rights in exchange.

At the initial stage, the process is presented as an exchange: the people gain something real and, for the time being, do not feel any concrete loss. In the next stage, however, the constructed savior-leader status gradually turns into a debt mechanism (Mieczysław P. Boduszyński, Vjeran Pavlaković, 2019). What was once a nationwide achievement—the victory—is now presented as a “gift” bestowed by the authorities. From this point on, the relationship ceases to be one of equal political citizenship and transforms into a relationship of dependency. Although the message is not stated explicitly, the core logic shaping political behavior is clear: “we gave you land, you owe us silence.”

At this point, the meaning of victory fundamentally changes. Instead of the expectation that “victory will expand the rights of the victorious people,” it turns into a tool that legitimizes obedience. This is precisely where the mechanism is completed: first, society is freed from a historical pain, and then the price of that liberation is extracted through enforced political silence—“made to come out of one’s nose.”

Post-war psychology and a silenced society

War is not limited to military actions on the battlefield; it also functions as a broad socio-psychological phenomenon that significantly reshapes society’s psychology. After the war, the desire for security and unity that emerges within society eliminates the space for healthy debate. In this context, war activates four dangerous reflexes that together form the psychological foundation for the transition from authoritarianism to dictatorship.

First, the mobilization rhetoric formed during wartime is carried over into peacetime. Any criticism directed at the authorities is presented as a “blow to the spirit of unity.” Criticism is thus framed as a threat to collective security, giving rise to fear and self-censorship.

Second, political opposition and alternative views are demonized through the concept of a “second front.” The authorities equate internal political competition with the struggle against an external enemy. This approach characterizes the very existence of opposition as activity against the state.

Third, war leads to the normalization of state violence. The harshness applied during wartime continues into peacetime. Legal restrictions, police violence, and repressive mechanisms are presented as matters of “state security.” Violence ceases to be an exception and becomes the primary method of governance (Elman Fattah, 2025).

Fourth, the idea generated by war—that “now is not the time to speak”—turns into a permanent political norm. Any criticism is countered with arguments such as “when the time comes” or “after the danger has passed,” yet that time never arrives.

As a result of these four reflexes, people remain silent even without overt repression, because they have already internalized the risks of speaking out. At this stage, authoritarian control shifts into a more complex and sustainable form: fear is no longer produced solely by the state but is also reproduced within society itself (Nigar Shahverdiyeva, 2025).

The transition of authoritarianism into a new phase

In classical forms of authoritarian systems, repression is usually employed as one political instrument among others. That is, repression serves to achieve specific political objectives or to minimize certain risks: neutralizing opposition before elections, suppressing protest waves, or punishing particular elites. This type of repression recognizes certain limits and is often kept “measured” in order not to completely lose international legitimacy. Azerbaijani authoritarianism likewise preferred this form before the victory. Periodic short waves of repression were followed by amnesty decrees. The preventive nature and short duration of the 2003, 2005, and 2013–2014 repression campaigns are clear examples of this pattern (Freedom House, 2015).

At the current stage, however, the political logic of Azerbaijani authoritarianism has fundamentally changed. Repression has ceased to be a means to an end and has become the system’s primary method of governance. The authorities’ main priority is not only to eliminate concrete political rivals but also to create a permanent climate of fear that categorizes everyone as a potential risk. Under these conditions, legal relations lose their regulatory function; the law is no longer a framework guiding behavior but a formal curtain used retroactively to justify violence. The real mechanism of governance is no longer law but the unpredictability of fear (Kharcenter, 2015a).

In this phase, the state itself operates as a threat mechanism. For citizens, the central question is no longer “what is illegal?” but “what is dangerous?” The uncertainty of rules becomes the main factor shaping behavior. Thus, repression turns into a structural element of everyday life and the key mechanism ensuring regime durability.

For Azerbaijani authoritarianism, the primary political threat is no longer only opposition actors but the very existence of society as a political subject. Repression is now applied systematically to reduce this possibility to zero. This signifies the transition of authoritarianism into a deeper and far more difficult-to-reverse phase—dictatorship (Kharcenter, 2015b).

Peoples who rush to rejoice

Political history reveals a paradoxical pattern: the onset of authoritarian catastrophes is often nourished by moments of collective joy. Societies suffer their gravest political losses precisely when the belief that “the danger is over” becomes dominant.

The political history of the twentieth century is highly instructive in this regard. In Germany, Russia, Italy, as well as in many countries of Latin America, despite differing historical, cultural, and ideological contexts, the same psychological chain was activated. Each of these societies collectively embraced the triad of “the danger has passed,” “the state has saved us,” and “now is not the time to protest” after a certain success. At precisely this moment, the extraordinary powers of the state cease to be temporary instruments and become permanent rules. Declaring protest “untimely” leads to the abolition of rights, calls for “unity” eliminate pluralism, and the prioritization of security results in the disappearance of law. Rejoicing and relaxed societies unknowingly lose their political immunity. As a result, after some time, there remains neither space to protest, nor legal justification for it, nor an institutional framework that would allow it (J. Tyson Chatagnier, 2012).

Today, Azerbaijan is passing through exactly this psychological stage. The post-victory sense of relief and the illusion that danger has ended have weakened society’s political reflexes. For societies, this is the most dangerous moment: when they rush to celebrate, without yet realizing what they have lost in return.

Models in Which Triumph Turns into an Authoritarian Disaster

The political experience of the last hundred years clearly proves that legitimacy gained through national victory or revival is the natural fuel of authoritarian consolidation. This process operates regardless of ideological colors, geographic location, or cultural context. Whether right-wing, left-wing, nationalist, socialist, or based on religious ideology, what matters is the psychological advantages brought by victory and how they are converted into political capital. One of the most striking examples of this phenomenon in history is Germany. After World War I, Germany faced a major crisis. The country experienced a difficult defeat both militarily and psychologically. As a result of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was punished and its sovereignty was restricted. Society also underwent a series of traumas. The loss of imperial status, economic stagnation, and hyperinflation are among the main aspects of these traumas. This created favorable conditions for the rapid growth of Nazism (Kenneth Barkin, Jan., 2026).

Hitler, in a very short time, presented society with a “formula for success”:

- Strengthening nationalism and eliminating the sense of humiliation among people;

- Rapid industrialization and economic revival;

- Reducing unemployment, promoting economic growth, and preserving social stability;

- Reviving the concept of an “Unchained Germany” (United States Holocaust Museum.)

These great successes led the German people to view Hitler as a savior, to mythologize him, and ultimately to treat the inviolability of his legitimacy as a given. However, the price of this legitimacy was very high. Along with the strengthening of the savior myth, the system quickly began to isolate itself. The Nazi regime systematically physically eliminated the opposition and completely abolished political competition. It turned the media into an ideological instrument of the state and the army into an ideological machine. By fully mobilizing society, it restricted individual freedoms.

As a result, a system that initially gained legitimacy by restoring lost honor turned, in a short period of time, into a regime of totalitarian control. German society felt strong for a while, but this “victory” became the beginning of a path that would end with the loss of thousands of people and the catastrophe of the country (theIASHub, 2025). This example clearly demonstrates the extent to which legitimacy based on the myth of salvation can lead to failures.

In the twentieth century, one of the notable examples of authoritarian regimes emerging in Latin America around the concepts of “salvation” and “security” is Chile. The military coup carried out in 1973 under the leadership of Augusto Pinochet was explained to society as the “end of chaos,” the “salvation of the state,” and the “elimination of the communist threat.” The Pinochet regime presented itself as a project fighting chaos. The portrayal of the socio-economic problems experienced during Salvador Allende’s period as the reason for military intervention was also easily “digested” by society. Pinochet likewise stated that these events had placed the country in a difficult situation and that harsh measures were necessary for Chile to be saved from bankruptcy. Under these conditions, he saw political opposition as a threat to national security. At the same time, through economic liberalization and market reforms, he increased his credibility both domestically and internationally. In particular, the economic reforms implemented by the “Chicago Boys” gave the regime a modern and technocratic appearance. This made it possible to justify a dictatorship that ensured security on the principle of economic efficiency. However, the regime’s true nature soon revealed itself. During the Pinochet period, tens of thousands of people were subjected to torture. People disappeared for a long time or were executed without any legal procedure. Political parties and civil society were completely destroyed (AP, 2023).

As a result, an impact even heavier than physical repression emerged. Society could not escape the climate of fear for a long time. People were forced to adapt to a psychological condition in which speaking, protesting, and even reviving memories were considered dangerous activities. Even after democracy was established, this fear negatively affected political participation for a long time (Meghan L. Rogers, 2025).

The same is happening in Azerbaijan: security → silence → dictatorship. The Chilean experience proves that “security systems” presented as “salvation” create long-term traumas in society. Several generations have to pay the price for regaining freedom.

Structural Comparison of the Azerbaijani Variant with Historical Models

Based on the historical examples noted above, the Azerbaijani model should also be understood not as a “nationally specific” event, but as a regional expression of the same authoritarian mechanism. The differences appear in style, rhetoric, and international context. Yet the internal logic of this mechanism remains almost constant. It is precisely the structural parallels that make this reading analytically more meaningful.

1st parallel: Victory

The initial stage of authoritarian consolidation almost everywhere begins with victory eliminating pluralism. In Germany, the Treaty of Versailles was assessed as a “national humiliation,” and this completely eliminated the possibility of rational discussion. In Chile, the “communist threat” blocked the political atmosphere as a whole (Marian Schlotterbeck, 2014). In Azerbaijan, the victory in Karabakh played a similar role: after the war, political discussions became impossible, and differing views are harshly punished. This stage establishes the same norm in all systems: “we are no longer obliged to tolerate protest and criticism.” This sentence reflects the psychological beginning of the transition from authoritarianism to dictatorship.

2nd parallel: The savior’s identification with the state

In the next stage, the leader begins to be perceived as the state itself. Hitler was identified with Germany, Stalin turned into the ontological center of the state, and Pinochet was presented as the living embodiment of security and “order” (Malcolm Coad, 2006).

A similar process is observed in Azerbaijan as well: Ilham Aliyev is gradually coded as a symbol of the state. At this stage, a consistent semantic slide occurs: criticizing the leader is presented not as targeting the government, but as targeting the state.

3rd parallel: Replacing law with security

In all examples, the third stage is the dismantling of law. The process usually unfolds in the same sequence: first law is weakened and made flexible, then security is declared the supreme priority, and finally security completely squeezes out law (NATHALIE A. SMUHA, 2024). This mechanism is familiar to all of us in Azerbaijan. The constitution has ceased to be a normative framework and has turned into a “collection of Ilham Aliyev’s powers,” the courts play the role of an executive mechanism, and legal categories are replaced by the concept of “threat.” At this stage, repression begins to function as the primary form of governance.

4th parallel: Indebting the people

In all of these historical models, an invisible mechanism also operates: indebting the people. First, society is “rewarded” with a savior; victory, stability, and order are delivered. Then this “blessing” is transformed into a political debt called loyalty. In Germany, this debt was national pride; in Chile, it was security. In Azerbaijan, both formulas are expressed: “We bestowed on you land and national pride. You gave us your voice.” After this stage, society functions like a hostage; people lose their citizenship rights and become a stratum paying the price for the “blessing” that was given.

Thus, comparison of analogous examples shows that Azerbaijan’s experience is neither historically exceptional nor new in terms of mechanism. The difference lies only in the spirit of the times.

Conclusion

This analysis revealed that the political hardening observed in Azerbaijan after 2020 is a modern regional form of a universal authoritarian tendency. Victory criminalized pluralism, the “savior” archetype returned to the agenda, law was sacrificed to security, and repression became the main form of governance. As a result, the society “indebted” through a “great success” completely lost its political subjectivity.

As in historical examples, this mechanism operates in Azerbaijan according to the same principle: the regime enters a deeper stage of one-man authoritarianism and total control in which the opposition is rendered ineffective. However, the “special risk zone” of the Azerbaijani model at this stage is the synthesis of oil revenues, information control, and digital repression. This synthesis gives the regime an appearance of greater resilience and longevity. Yet this stability is a construct supported by resources and protected by psychological control; it relies not on institutional mechanisms capable of renewal, but on the emotional and material sources of legitimacy.

It is clear that this model will not be able to withstand the structural test of the post-oil period. As oil revenues decline, the financial foundations of the “social silence contract” will weaken. This will lead to the reduction of paternalist welfare instruments and to the loss of the effect of purchased loyalty against political risks. In the post-oil period, the difficulties the regime will face (unemployment, social injustice, low-quality services, pressure on the budget, and the shrinking of the middle class) will surface as various forms of legitimacy crisis. Although the inviolability formed by the myth of victory may function for some time as a “psychological wall,” it will gradually collapse in the face of the increasingly difficult realities of everyday life. Therefore, even if the Azerbaijani model appears at first glance to be resilient and long-lasting, its weak sides will emerge sharply in the post-oil period.

Victory legitimacy does not possess the power of an “endless political mandate”; it is political capital that will rapidly lose its significance when confronted with economic and institutional collapse. Information control and digital repression may only prolong growing discontent during periods of economic hardship, but cannot eliminate it. Finally, although replacing law with security may protect the regime in the short term, in the long term it reduces the state’s flexibility and leaves it defenseless against post-oil shocks.

Thus, the post-war period will test all pillars of Azerbaijani authoritarianism that appear strong today (the myth of victory, the obedience regime built on “security,” the information monopoly, and the digital surveillance system) simultaneously—just as in the historical analogies presented in comparisons. This test will clearly show that Azerbaijani authoritarianism, which today appears stable and long-lasting, is in fact a typical “failed state model.”

References:

Arif Quliyev, 2024. XİLASKAR. https://files.preslib.az/projects/heydaraliyev/articles/he1618.pdf

Neta C. Crawford, Catherine Lutz, 2025. Long War & the Erosion of Democratic Culture. https://direct.mit.edu/daed/article/154/4/161/134167/Long-War-amp-the-Erosion-of-Democratic-Culture

Giorgi Gogia, 2025. Azerbaijan Escalates Crackdown on Exiled Critics. https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/11/26/azerbaijan-escalates-crackdown-on-exiled-critics

Mieczysław P Boduszyński, Vjeran Pavlaković, 2019. Cultures of Victory and the Political Consequences of Foundational Legitimacy in Croatia and Kosovo. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8280552/

Elman Fattah, 2025. The Stability and Legitimacy Mechanism of Azerbaijani Authoritarianism. https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-stability-and-legitimacy-mechanism-of-azerbaijani-authoritarianism

Nigar Şahverdiyeva, 2025. Artıq işgəncə yoxdur, amma itaət var. https://sia.az/az/news/social/1295291.html

Freedom House, 2015. Azerbaijan Consolidated Authoritarian Regime. https://freedomhouse.org/country/azerbaijan/nations-transit/2015

Kharcenter, 2015a. MIRAS: Azerbaijan’s Digital Repression Architecture. https://kharcenter.com/en/researches/miras-azerbaijans-digital-repression-architecture

Kharcenter, 2015b. MIRAS: Azerbaijan’s Digital Repression Architecture. https://kharcenter.com/en/researches/miras-azerbaijans-digital-repression-architecture

J Tyson Chatagnier, 2012. The effect of trust in government on rallies ’round the flag. Pages 631–645. https://academic.oup.com/jpr/article/49/5/631/8365825

Kenneth Barkin, Jan. 2026. Years of crisis, 1920–23. https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/Years-of-crisis-1920-23

United States Holocaust Museum. Building a National Community, 1933–1936. https://www.ushmm.org/learn/holocaust/building-a-national-community-1933-1936

theIASHub, 2025. Nazism: Rise, Causes, and Global Consequences of Hitler’s Totalitarian Ideology. https://theiashub.com/free-resources/world-history-1744631154/nazism-1750414826

AP, 2023. years after coup ushered in brutal military dictatorship. https://apnews.com/article/chile-coup-anniversary-pinochet-allende-boric-c00adad8026a5dc54f2834ef9c31fb8a

Meghan L. Rogers, 2025. The Illusion of Order: Authoritarian Repression and Non-State-Sponsored Homicide in Chile, 1960–2020. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43576-025-00197-x

Marian Schlotterbeck, 2014. Breakdown of Democracy in Chile. https://academic.oup.com/book/56192/chapter/443482519

Malcolm Coad, 2006. Augusto Pinochet. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/dec/11/chile.pinochet4

NATHALIE A. SMUHA, 2024. How algorithmic regulation in the public The sector erodes the rule of law. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/DB549609A55E92DB12157CC965C2CF84/9781009427463AR.pdf/Algorithmic_Rule_By_Law.pdf