(This article is prepared within the KHAR Center’s research series on Azerbaijani authoritarianism)

Note:

The initial version of the Regulation on the Centralized Information and Digital Analytics System (MIRAS) was briefly published on the official website of the President of Azerbaijan, but the page was later removed from the internet without any formal explanation. Nevertheless, since the document had already entered public circulation and was archived by several sources, we rely on the complete PDF version provided by Cavid Ağa. Our analysis is based precisely on this preserved copy of the official text.

Introduction

In November 2025, with the signing of the corresponding decree by the President, the statute on the Centralized Information and Digital Analytics System — MIRAS — of the State Security Service (SSS/DTX) of the Republic of Azerbaijan entered into force. In official discussions, MIRAS is presented as a modern information platform that “accelerates” state administration, “integrates” the digital ecosystem, and “increases transparency.” In this context, MIRAS is introduced as a technical mechanism aimed at making state services more efficient, coordinating resources, and managing information flows more effectively.

However, when one examines the legal and technical structure of the system, it becomes evident that MIRAS actually functions as a centralized intelligence, surveillance, and behavioral analytics mechanism. The platform consolidates the extensive databases stored in state registries. It synchronizes security agencies with cameras and other video-surveillance systems. The collected data is then used for behavioral prediction and the making of operational decisions.

The model created mirrors the “integrated state surveillance” networks developed in China, Russia, and Kazakhstan.

The main thesis of this analysis is the following: MIRAS brings Azerbaijan’s governance model into an entirely new phase of digital authoritarianism.

A Full Transition to a Security State

The statute defines the role of MIRAS not as a digital service infrastructure but as a platform for security, automation, and the digital coordination of repressive operations. The system operates within the framework of the laws on “Intelligence and Counterintelligence Activities,” “Operational Investigative Activities,” “State Secrets,” and “Combating Terrorism.” This places MIRAS squarely at the forefront of regime security through the State Security Service.

The statute grants the SSS real-time access to various data sources; the data is processed analytically and used in the decision-making of operational activities.

As a result, MIRAS becomes a centralized technological model in the state’s information ecosystem for obtaining, producing, and processing data. Its structural foundations fully support this politico-functional nature. This infrastructure is created not only for the storage of information but also for the application of automated analytical modules, behavioral prediction, and enhancing the efficiency of decision-making processes. Integration with the Electronic Government Information System (EGIS/EHIS) provides MIRAS with real-time access to numerous state registries — financial transactions, real estate, migration, transport, criminal prosecution, banking data, and mobile operator information.

Furthermore, MIRAS does not merely collect information sources — it centralizes them and reinterprets them for the security purposes of the regime. This approach allows the authorities to monitor citizens’ behavior in a more systematic manner.

The fact that the same legal actor — the State Security Service — acts as both owner and operator of the oversight and administrative functions gives the system a monolithic character that maximizes securitization.

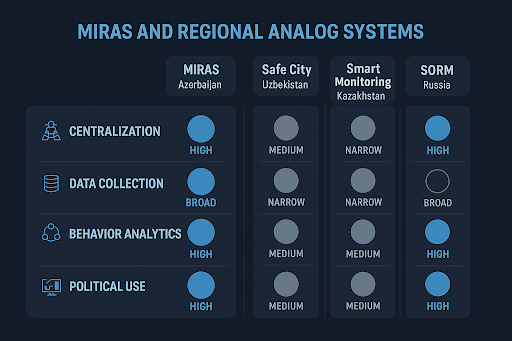

This model is unique even on the international stage. In democratic countries, comparable systems are strictly confined to counterterrorism (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2022). MIRAS, however, becomes a core resource for expanding the control mechanisms of the information regime. This feature makes it comparable to the authoritarian versions of Uzbekistan’s “Safe City” program (Kun Uz, 2019), Kazakhstan’s “Smart Monitoring” platform (Eurasian Research Institute, 2020), and Russia’s SORM system (Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, 2022).

The Scale of Data Consolidation: Total Profiling

The data environment defined in the statute demonstrates that the regime is building a system of complete societal control through MIRAS. The information fed into the system is not limited to basic identification data. It encompasses various aspects of an individual’s life — from physical movements to family ties, from medical histories to religious beliefs, from border crossings to social payments.

Identity documents, passports, personal identification numbers (PIN), and facial recognition systems (3.2.1), residence and registration information (3.2.2), vehicle and driver information (3.2.3–3.2.*) represent only the simplest level of the system.

MIRAS’s integration with security services makes the picture even clearer: arrest and prosecution summaries, data on criminal cases, information on individuals wanted by law enforcement, and investigation materials. This means personal information becomes an element of the intelligence-data stream processed by the analytical modules of the SSS. Such an approach aims to establish a flexible governance system through preventive repression mechanisms.

The system also gathers data on family structure and social status, bringing surveillance into private spheres. The identification of family members (3.2.11) provides ideological resources for assessing regime loyalty and political categorization.

One particularly concerning area is the integration of the healthcare system: alongside general medical information, psychiatric and narcological registration data is included. Granting security agencies access to such sensitive information threatens both the inviolability of private life and the protection of individual rights. The conversion of medical histories into instruments of security resembles the use of personal data as a state resource in totalitarian regimes.

Beyond this, MIRAS creates socio-economic profiles by centralizing traces of economic behavior. This includes employment contracts, social payments, and income tracking (3.2.21–3.2.22), as well as entrepreneurship and tax registration (3.2.28), and even utility service information (3.2.27). Profiling within such a wide range transforms the citizen from a rights-bearing individual into a governed object — a subject of control.

An additional module on public servants — covering career information and disciplinary sanctions (3.2.26) — demonstrates the centralization of elite oversight as well. The main purpose here is to monitor intra-system loyalty.

The inclusion of passenger registries in air transportation (3.2.31) and special registration for trips to Karabakh (3.2.34) indicates that surveillance extends to geographical mobility. This allows real-time tracking of a citizen’s movement trajectory.

All such data, centralized under the pretext of “security,” will undoubtedly be used to increase societal control.

Possessing such a rich data repository allows MIRAS to build a digital profile of any individual. This profile does not merely reflect the person’s identity or legal status but also maps their social connections, circles of communication, economic behaviors, daily activity patterns, medical conditions, psychological and social risk factors. At the same time, the profile makes it possible to assess an individual’s stance toward the regime.

In other words, unlike the classical method of legal prosecution — the “post-factum punishment” model — MIRAS enables a “pre-factum control” principle based on evaluating intention.

In the absence of democratic oversight mechanisms — independent courts, parliamentary inquiries, an autonomous ombudsman, and public accountability — power at this level automates and obscures repressive strategies. A digitalized profile becomes an algorithmic filtration tool for measuring political loyalty and mapping oppositional behavior.

Consequently, MIRAS modernizes the traditional forms of authoritarian governance. Overt repression is replaced by covert, data-driven, preventive, and selective surveillance methods. The role of the physical police post is now assumed by digital monitoring, algorithmic suspicion, and data-oriented behavior engineering. This approach turns individuals into laboratory subjects governed under security principles.

Legal Gaps and the Absence of Oversight Mechanisms

One of the most critical aspects of the statute is that MIRAS is kept outside legal oversight mechanisms. The system does not require a court order to access relevant information. Nor is there any requirement for subsequent judicial or prosecutorial review of operations. Moreover, the citizen — the owner of the data — does not have the right to be notified when their information is accessed or manipulated.

In democratic systems, the legitimacy of large-scale security and surveillance infrastructures is ensured through parliamentary monitoring and annual public reports. The absence of parliamentary oversight and the lack of mandatory annual public reporting on the activities of security agencies turn MIRAS into an exceptionally empowered instrument of the regime. This leaves access to information entirely dependent on internal executive decisions and assigns control to administrative procedures. In other words, control over data is directed entirely toward one purpose: protecting the regime from society.

In cases of incorrect or incomplete data, individuals are not treated as legal subjects. Within the framework of MIRAS, the correction of erroneous data is not handled by an independent arbitration body or court but is resolved based on the decision of the state agency responsible for entering the data. Implementing corrections without court involvement places priority not on verifying information but on keeping data in a form that suits the system.

Thus, MIRAS plays a dominant role not only in data collection but also in decision-making regarding that data.

Sensitive Categories: Medical and Psychological Data

The statute integrates into the MIRAS system not only general medical information but also more sensitive personal data such as psychiatric and narcological records, directly placing them under the regime’s security mandate. Processing such information within a security framework can produce serious political consequences. This is because what is known as “punitive psychiatry” was historically one of the tools authoritarian regimes used to neutralize dissidents. Labeling dissidents as “psychologically unstable” and classifying them as criminals or the mentally ill was widespread in the USSR (HRVV, 1990). In Azerbaijan, where the post-Soviet nomenklatura still maintains dominance, there is little doubt that this old KGB method will now be applied more systematically in a modernized form.

The concentration of such data under the control of the SSS creates serious risks for political activists. In the near future, presenting individuals who oppose the regime as “psychologically unstable,” “emotionally inconsistent,” or possessing “high public danger potential,” and exploiting medical records for media-based reputational attacks, will become more systematized. Unlike criminal charges, this is a subtler but equally effective form of repression built on portraying political opponents as “abnormal.” MIRAS will enable these processes to be executed without any legal procedure. This elevates authoritarian control to a level that is even harder to criticize.

Within MIRAS, fabricated psychiatric and narcological data will pathologize oppositional behavior. The danger of this method lies in linking repression with the fetishization of medical expertise.

Digital Methods of Strengthening Authoritarianism

The official framework presents MIRAS as a security-centered infrastructure that protects state-owned critical information within the country. The document emphasizes that data is not transferred abroad and that the platform has the status of a national security asset. All information resources are considered state property. On paper, these concepts may be presented as “national independence” and “data sovereignty.” However, the real functional direction of this architecture is different: the system enables the regime to establish maximum informational control over citizens. Here, the notion that “the state protects data” effectively reads as “the regime collects, stores, and uses the data.” The citizen is regarded both as a producer of information and as a security subject.

Storing data within the country and designating it as state property does not in fact increase the citizen’s security. On the contrary, these measures further weaken the citizen’s rights over their own data. This is because data protection becomes dependent not on international legal frameworks but on the domestic administrative system. As a result, the control of information depends not on objective legal mechanisms but on political will.

In this model, the state does not establish an equal relationship with citizens; it retains information as a security resource exclusively in its own hands, thereby obtaining a unilateral informational advantage. Although citizens must submit their data to the state, the state is not obliged to explain how this information is used, for what reasons, and under what risks. Thus, the model does not contribute to strengthening the state vis-à-vis international actors; instead, it contributes to keeping the state’s own society under total control.

In other words, in the case of MIRAS, the principle of “the state protects the citizen” transforms into the approach “the state keeps the citizen under surveillance.”

Where Is MIRAS Taking Azerbaijan?

When responding to criticisms of the MIRAS program, the Azerbaijani government will likely point out that large-scale digital surveillance and data integration systems exist not only in authoritarian regimes. It would be possible to claim that the United Kingdom, France, and other democratic European states also have similar systems. This idea may appear accurate when viewed through the lens of technological similarities. However, fundamental differences emerge in the purposes of the systems, their legal regulation, institutional transparency, and political neutrality. Put differently, the similarities lie only in the technology used, not in the principles of governance. The claim that MIRAS resembles Western models creates the need to compare how democratic systems and authoritarian regimes use these technologies.

The United Kingdom possesses an extensive CCTV system and has long been at the center of debates about the “surveillance state.” The integration of CCTV cameras with police databases and facial recognition systems, as well as intelligence exchanges between MI5, MI6, and GCHQ, creates large-scale surveillance capabilities from a technical standpoint. The Investigatory Powers Act grants internet providers the ability to collect metadata on a wide scale (Investigatory Powers Act 2016). This is the only detail that could “justify” the Azerbaijani government’s possible claims regarding technical parallels.

The main feature that differentiates the British model from authoritarian surveillance systems is that this infrastructure is placed within a clearly defined legal framework. Every data request is reviewed under judicial oversight and must be approved by a designated Investigatory Powers Commissioner. If state institutions use collected information for political purposes, they bear serious accountability. In addition, citizens’ right to access their own data is guaranteed by law (Parliament UK, 2016).

In conclusion, although large-scale surveillance exists in the UK, it is balanced by democratic principles — transparency, independent oversight, court orders, and political neutrality.

After 2015, France enhanced its security measures against terrorist attacks by implementing real-time metadata tracking systems and behavioral analysis based on risk profiles. Within the “Vigipirate” and “Sentinelle” programs, different databases are brought together. Thus, France indeed has robust surveillance capabilities from a technical point of view. However, two key limitations differentiate it significantly from MIRAS.

First, it is prohibited to create a full behavioral profile of a citizen without concrete suspicion of a crime.

Second, all surveillance-related activities are regulated by another institution — the CNIL, the national data protection authority (Pandectes, 2023). Likewise, data integration is not permitted without parliamentary oversight and a judicial decision. The retention period of collected data is strictly defined by legal requirements, and the creation of permanent profiles is forbidden.

Although the French model provides extensive technical surveillance capabilities, it is heavily constrained by transparency requirements, independent regulatory authorities, and principles of political neutrality to preserve democratic balance.

Nevertheless, human rights organizations criticize both the UK and France on these issues. In both countries, the intensive collection of metadata and the rapid expansion of facial recognition technologies are viewed as trends contrary to democratic principles (Big Brother Watch, 2023).

However, these criticisms do not claim that the UK or France are moving toward authoritarianism; rather, they underscore the importance of ensuring the right balance between security and freedom (Amnesty International, 2014).

These two examples demonstrate that who conducts the surveillance, for what purpose, under what legal basis, and with what institutional checks determines whether the system has an authoritarian nature.

In Azerbaijan, MIRAS serves as a digital model of authoritarian governance precisely because these four elements are absent. A comparative perspective shows that MIRAS does not resemble Western-type systems. On the contrary, the architecture of MIRAS fully corresponds to post-Soviet and Asian authoritarian governance models.

In Russia, the joint monitoring and data-integration systems coordinated by the FSB designate state security as the core of the digital infrastructure (Juho Niskanen, 2023).

In this system, the intelligence service acts as the main hub that collects information and manages integrated data flows. In the Azerbaijani model, the fact that MIRAS is both owned and operated by the security agency — the State Security Service (SSS/DTX) — reveals the same concentration of power. This indicates that the primary function of the institution is an internal control mechanism.

In Kazakhstan, the merger of the “Smart City” project with the National Security Committee (KNB) was initially carried out under the banner of digitalization aimed at improving services. However, it later took the form of monitoring independent journalists and activists, and creating profiles of critics (HRVV, 2023). The real-time integration of Azerbaijan’s digital state systems with MIRAS — from utility services to education and healthcare registries — is a repetition of the Kazakh scenario.

The Chinese model stands out with an important distinction: surveillance there does not end with data collection but expands into a proactive governance approach through algorithmic evaluation of behavior and mechanisms of social ranking. “Skynet” is a platform where hundreds of millions of cameras are integrated with facial-recognition and analytical modules. This system makes it possible to generate behavioral profiles even from the physical movements of citizens (Cambridge University, 2025).

The combination within MIRAS of video-surveillance capabilities with analytical modules, its inclusion of psychiatric, social, and medical data, and its collection of information on border crossings and mobility patterns clearly show that the system will advance toward a similar stage of behavioral tracking.

For this reason, MIRAS possesses a hybrid architecture composed of selected elements from all three models:

- from China: video analytics, the collection of behavioral traces, and predictive algorithms;

- from Russia: the transfer of complete control over data integration to the security agencies;

- from Kazakhstan: the integration of the e-government infrastructure for security purposes.

Thus, the MIRAS service represents not the model of a rule-of-law state, but the digital model of a police state. Its institutional principles are formed on the basis of unified governance and profile-based preventive surveillance. If the system is fully implemented, it will create the first state-level centralized digital intelligence platform in the South Caucasus and will lead to the formation of new authoritarian governance standards in the region. This may also be interpreted as an attempt by the authorities to eliminate their unresolved legitimacy crisis through information control.

The Production of Obedience Through Information: The Core Political Function of MIRAS

The implementation of MIRAS not only poses an abstract threat to the freedoms of citizens but also creates a structural effect that changes behavior. Undoubtedly, the risk of surveillance will further increase the level of self-censorship in society. Before expressing a critical opinion, joining public demonstrations, or forming political affiliations, individuals will begin to consider concerns about potential monitoring. Here, the influence of surveillance stems not from its actual application but from the likelihood of being observed. This smooths the path toward a fully depoliticized society — one of the main objectives of Azerbaijani authoritarianism.

Digital surveillance also creates the risk of restricting access to social opportunities. Applying for employment in state institutions, participating in tenders, obtaining accreditations, acquiring visas, traveling abroad, and even accessing the banking system may lead to a “risk profile” being generated by MIRAS. In this model, political loyalty is not considered proven through explicit declarations. The regime will compare proof of loyalty with data analysis automatically extracted from patterns of behavior.

Surveillance also becomes an integral part of everyday bureaucratic activity. Whereas previously monitoring an individual required a special operation or a court order, now, within MIRAS, merely using e-services (such as registration, payments, or data updates) automatically transfers information to the security system. This makes voluntary sharing of data indistinguishable from using state services, depriving citizens of choice: either refrain from using services or appear “naked” in the eyes of MIRAS.

All of this transforms the citizen into a profile that can either receive or be denied opportunities based on their behavior. This represents a new phase of authoritarian governance: achieving obedience through data rather than violence.

Conclusion

In the absence of mechanisms such as restricting data access through a court order, independent parliamentary and public oversight, the obligation of the data user to be accountable to the data owner, and the ability of individuals to correct or delete their data, MIRAS pushes Azerbaijan’s governance model into fully consolidated digital authoritarianism.

MIRAS implements the construction of a security state in Azerbaijan under the guise of digital transformation. The issue is not the existence of the technology itself; the issue is its application without legal oversight, without democratic balancing mechanisms, and entirely under the control of the security agencies. Technology is neutral by nature, but the political structures that possess this technology are not. Since this system will operate without genuine democratic principles, there is no longer any doubt that its purpose is to monitor people, target them, influence them, and ultimately turn them into obedient subjects.

In the system, control is created through the asymmetry of information collected by technology: the regime pre-determines behaviors, creates profiles, and takes preventive measures, while the citizen does not know which data is being tracked, how it is being evaluated, or which risk index they fall under. The state knows everything about the citizen, but the citizen does not know what the state knows about them. Naturally, the main goal of the regime is not to monitor every step of citizens, but to ensure that they believe they are being monitored. This belief normalizes self-censorship and increases political passivity.

In other words, MIRAS is the foundation of a digital obedience regime for Azerbaijan.

REFERENCES

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2022. National intelligence authorities and surveillance in the EU: Fundamental rights safeguards and remedies. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fr-surveillance-report-update-2022_en.pdf

Kun Uz, 2019. Huawei may be attracted to implement the “Safe city” project in Uzbekistan . https://kun.uz/en/86026439?q=%2Fen%2F86026439

Eurasian Research Institute, 2020. Digital Surveillance Solutions in Central Asian States. https://www.eurasian-research.org/publication/digital-surveillance-solutions-in-central-asian-states/

Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, 2022. Russia’s Surveillance State. https://cepa.org/article/russias-surveillance-state/

HRVV, 1990. PSYCHIATRIC ABUSE IN THE USSR. https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/pdfs/u/ussr/ussr.905/ussr905full.pdf

Investigatory Powers Act 2016. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/25/contents

Parliament UK, 2016. LEGISLATIVE CONSENT MEMORANDUM. https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/commons-public-bill-office/2016-17/legislative-consent-resolutions/Investigatory-Powers-Bill-LCM1-251016.pdf

Pandectes, 2023. France’s Data Protection Agency. https://pandectes.io/blog/an-overview-of-the-cnil-frances-data-protection-agency/

Big Brother Watch, 2023. State of Surveillance. https://bigbrotherwatch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/State-of-Surveillance-Report-23.pdf

Amnesty International, 2014. THE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE’S PRIVACY AND SECURITY INQUIRY. https://isc.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/20150312-PS-041-AI.pdf

Juho Niskanen, 2023. Russia’s ICT infrastructure and its development prospects in the near future. https://puolustusvoimat.fi/documents/1951253/2815786/15_Niskanen.pdf/cbaf50be-e7b8-6802-7c57-495c52943a9c/15_Niskanen.pdf?t=1696849366521

HRVV, 2023. World Report. Kazakhstan. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/kazakhstan

Cambridge University, 2025. Algorithmic regulation at the city level in China. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/data-and-policy/article/algorithmic-regulation-at-the-city-level-in-china/57D30B18C3A50C7208B3E6DFF88BBC74