Introduction

The protests in Iran that began in the final days of 2025 and have continued to grow are on the verge of becoming the next nationwide movement following the 2022 “Woman, Life, Freedom!” uprising. The unrest started with strikes by merchants in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar and the Aladdin Bazaar in protest against the rising exchange rate of the US dollar, and within a few days it both spread across the country and sparked international debate. In the first week of the uprising, the scope of the protests covered 21 of Iran’s 31 provinces. It has been reported that students in 10 major cities across Iran—including those studying at Tehran and Tabriz universities—have joined the movement (Yildiz 2026).

The protests have been accompanied by mass detentions. According to statements by various human rights organizations, it has so far been possible to identify the identities of 90 detainees in total, and it is reported that 15 individuals have been transferred to Evin Prison (Iran Intl. 2026). Although it is reported that six people have been killed, it is impossible to verify these deaths or to determine the true scale of fatalities (BBC 2026). Moreover, the widespread practice of extrajudicial punishment in Iran following the confrontation with Israel—now established as a precedent—has raised serious concerns regarding the fate of those detained.

At the same time, when examining the news feeds of Iran’s pro-regime agencies such as Tasnim, Mehr, and IRNA (Islamic Republic News Agency), it becomes clear that information about the unrest in the country is extremely limited. In its report published on January 2, IRNA stated that the protests were “civil” and “economic” in nature and that they had already ended (IRNA 2026a). In another report, the official news agency claimed that 14 “trained and organized terrorists” had been arrested in Alborz Province while preparing Molotov cocktails and other explosives (IRNA 2026b).

Instead of extensive reporting on the protests, attention has largely shifted to a statement made by US President Donald Trump via his social media platform Truth Social, in which he warned that the United States would intervene if the Iranian government were to “open fire on protesters” and “kill them” (Trump 2026). In the event of US intervention, Iran’s potential military responses—including the targeting of US bases in the region—have also been brought into focus (Tasnim 2026).

The 2026 uprisings are unfolding in a context shaped by the tandem of deepening authoritarian consolidation and economic crisis following the 12-day war with Israel. Therefore, to understand the driving forces behind the uprising, it is necessary to examine these two factors together.

In this analysis, the Khar Center examines the possible determinants behind the current protests. It explores both what has changed in Iran following the confrontation with Israel and the impact of the “snapback” mechanism—motivated in part by this confrontation—and renewed sanctions on Iran’s economy.

Research question: What are the political and economic factors triggering discontent in Iran? Given these political and economic parameters, what are the possible continuity scenarios for Iran?

The Link Between the Protests and the Economic Situation

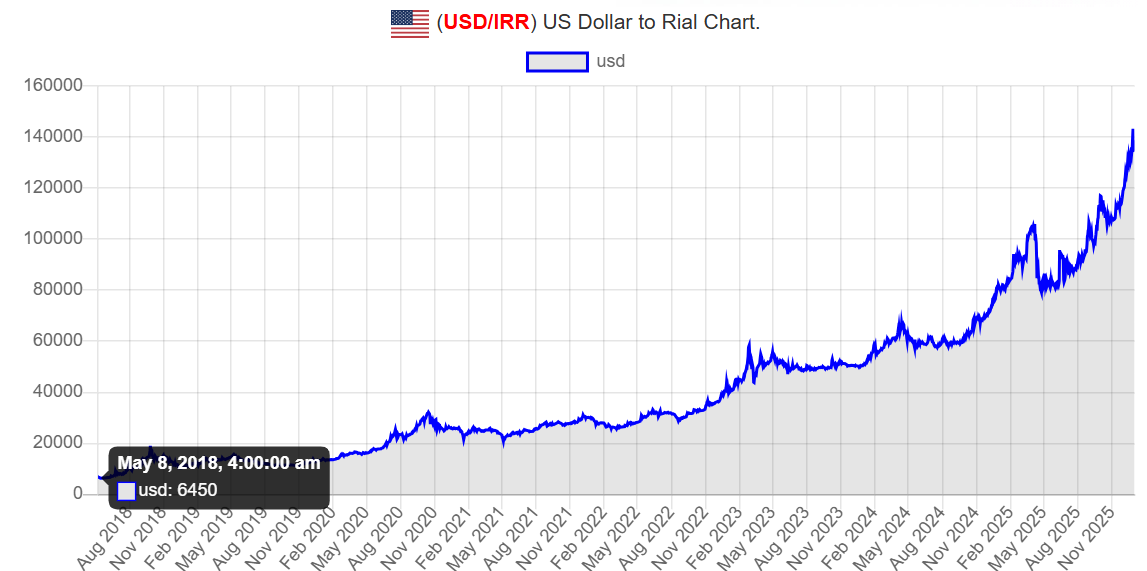

Alongside the classic slogan “Marg bar diktator” (Persian: مرگ بر دیکتاتور – “Death to the dictator”), which gained popularity during opposition to the Pahlavi regime, an examination of the slogans used in the current protests reveals that they are clearly rooted in economic demands. When we look at the real exchange value of the Iranian rial against the US dollar over the past eight years, we can observe that it has lost more than 21 times its value (Chart 1).

If we examine the Bonbast portal, which reflects the real market value of the Iranian rial inside Iran, we see that while on May 18, 2018, 1 US dollar was equal to 64,500 rials, this figure has now reached 1,350,500 rials (Bonbast 2026).

The choice of May 8, 2018, as a reference point is not coincidental. It was on that date that the United States announced its unilateral withdrawal from the diplomatic framework addressing Iran’s nuclear program—the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—and launched a “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran (Aksüt 2020). On August 7, 2018, the first phase of the sanctions package was implemented, targeting Iran’s trade in precious metals and gold, the automotive sector, and transactions conducted in Iranian rials. The second phase entered into force on November 5, 2018, dealing a blow to the energy and oil sector, maritime shipping, and the banking sector (Hannah 2021).

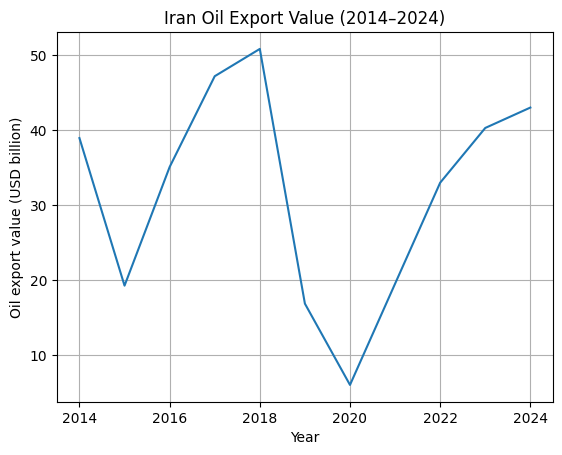

Sanctions imposed on the oil sector had an immediate effect. Iran’s oil export value, which stood at approximately USD 50.82 billion at the beginning of 2018, fell dramatically to around USD 16.85 billion within one year, and to USD 6.01 billion within two years (TradeIMEX 2025) (Chart 2).

Chart 1. Domestic market value of the Iranian rial relative to the US dollar (by years). (© Bonbast.com)

In subsequent years, although the indicator showed a positive upward trend due to increased exports to China (Chart 2), the “maximum pressure” campaign—combined in a complex manner with other ongoing domestic and external factors—became one of the key drivers behind the loss of confidence in Iran’s exchange rate. Another external factor contributing to the erosion of trust in the Iranian rial is the historical trajectory of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) mentioned above. Expectations generated at various periods by the course of diplomatic negotiations had a dramatic impact on the Iranian rial.

Negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program, which were resumed in 2013, reached a conclusion on July 14, 2014, with the participation of the European Union, the permanent members of the UN Security Council, and Iran, and through the mediation of the E3 group (the United Kingdom, Germany, and France), which acted as moderators of the diplomatic talks on Iran’s nuclear program: the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed (Council of the European Union 2025a). The Action Plan aimed at lifting sanctions imposed on Iran in parallel with the parties’ compliance with the commitments they undertook.

Following the confrontation with Israel in 2025 and the United States’ targeting of Iran’s nuclear facilities, Iran’s suspension of cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency resulted in the E3 countries activating the “snapback” mechanism (UK Government 2025). Thus, from September 2025 onward, all UN sanctions imposed during 2006–2010 once again became fully effective. The collapse of the JCPOA and the subsequent activation of the “snapback” (“sudden reinstatement”) mechanism—leading to the restoration of all UN sanctions—have extinguished hopes that the Iranian rial might recover.

Subsequently, in a press release issued on September 29, the Council of the European Union announced that additional restrictive measures would be imposed on Iran (Council of the European Union 2025b). These restrictive measures include:

- Travel bans on individuals, the freezing of assets of individuals and entities, as well as the prohibition of making funds or economic resources available to listed persons and entities.

- Economic and financial sanctions, including restrictions covering the trade, financial, and transport sectors.

- A ban on the import, purchase, and transport of crude oil, natural gas, petrochemicals, and petroleum products, as well as on the provision of services related to these activities.

- The suspension of the sale or supply of key equipment used in the energy sector.

- The suspension of the sale or supply of gold, other precious metals, and diamonds.

- A ban on the sale of certain naval (military) equipment.

- A ban on the sale or supply of certain software.

- The renewed freezing of assets of the Central Bank of Iran and major Iranian commercial banks.

- The prevention of Iranian cargo flights from accessing EU airports.

- The prohibition of providing technical maintenance and servicing to Iranian cargo aircraft or vessels carrying prohibited materials or goods.

Despite the fact that revenues from oil production—petrodollars—have shown a positive trend, the Iranian rial continues to weaken. This is because a large share of exported oil is sold below market prices, at discounts, while payments are often delayed, conducted through barter arrangements, or frozen in controlled accounts abroad. Moreover, these revenues do not freely enter Iran’s banking system and therefore do not generate a supply of hard currency liquidity within the country.

Even when Iran earns revenue from oil sales, it is unable to exercise full financial control over these funds. A significant portion of the money is held in escrow or restricted-use accounts in China, Iraq, and other countries. These funds can only be used for pre-approved import operations and are not directed to the open currency market. The Central Bank of Iran is thus deprived of the ability to use these reserves to defend the rial, intervene in the market, or stabilize currency expectations. As a result, the rial effectively remains in a “floating” state under conditions of persistent foreign currency scarcity.

Chart 2. Value of Iran’s oil exports (by years) (in US dollars) (Data: TradeIMEX)

The financing of government expenditures is increasingly carried out primarily through money issuance, domestic borrowing, and various quasi-fiscal institutions, which in turn deepens inflation and weakens the rial’s purchasing power. Rising inflation increases demand for foreign currency in the open market, thereby putting additional pressure on the national currency.

The multi-tier exchange rate system implemented in Iran also seriously undermines financial confidence. The official, semi-official, and free-market exchange rates that exist in parallel expand arbitrage opportunities, grant informal advantages to certain groups, and discourage the population from saving in the national currency. Both households and business entities prefer to channel their savings into dollars, gold, or real estate. In this context, the rial is perceived not as a store of value, but as a risky asset that rapidly loses value.

The state of exchange rates is also shaped by expectations about the future. Financial markets “assume” that sanctions will remain in place for the long term, that political uncertainty will persist, that there are risks of regional escalation, and that there is no credible path of economic reform. For this reason, even positive news about oil production and exports does not change expectations and does not remove pressure on the rial.

In the 2000s, oil revenues were one of the main factors preserving the stability of Iran’s national currency. During that period, the country had access to the international banking system, could mobilize its foreign currency reserves, and could draw on fiscal buffers. Today, however, the situation is fundamentally different. Iran has oil, but it does not have monetary sovereignty over the revenues derived from that oil. As long as sanctions block currency circulation, oil production may appear stable on charts, but the rial’s depreciation will continue to have a structural character.

Political determinant: the effects of the 12-day war and growing consolidation

The replacement of the decades-long “shadow war” between Iran and Israel with a 12-day direct military confrontation that took place on June 13–24 produced profound changes in Iran’s domestic governance structure, ideological foundations, and regional strategic plans. These changes were so colossal that the Iranian state rebuilt its security paradigm and transitioned to a “Proactive Security Doctrine” (Toğa 2025).

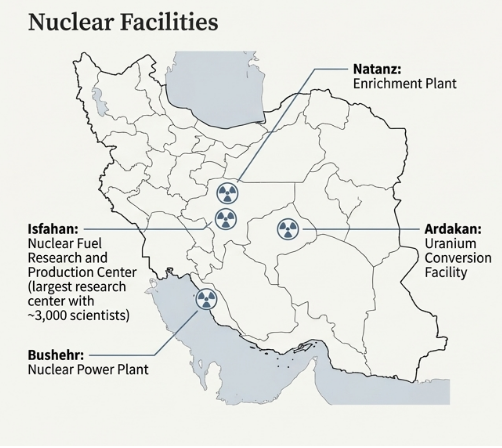

Israel’s “Mitva Am ke-Lavi” (“The Rule of a People Like a Lion”) operation delivered heavy blows to Iran’s most sensitive points—its nuclear infrastructure, command-and-control centers, and elite military personnel. US air strikes, carried out with the participation of an Israel openly aligned as an ally in the confrontation, disabled the underground facilities at Natanz and Fordow as well as missile depots (Golkar 2025) (Map 1). Iranian officials later acknowledged that some air defense systems had been destroyed and replaced with domestic systems (Toğa 2025) (Map 2).

Map 1. Some nuclear facilities in Iran.

Alongside the disabled technical infrastructure, Iran’s military leadership also lost key figures. More than 30 high-ranking commanders—including IRGC Commander-in-Chief General Hossein Salami and senior leadership of the intelligence organization—along with dozens of nuclear scientists and hundreds of personnel from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), were lost (Golkar 2025). Losses of this magnitude created serious difficulties in the regime’s command-and-control chain and forced the state apparatus into a period of “capability restoration” (Toğa 2025).

Iran’s largest attack campaign to date, carried out with nearly 900 ballistic missiles and more than 1,000 drones, exposed significant gaps in the face of Israel’s technological superiority and pushed Tehran to restructure its missile/UAV production and distribution cycle (Golkar 2025; Toğa 2025). The reverberations of the confrontation on the “domestic front” manifested themselves in harsher governance, increased institutional centralization, and the imposition of total control over society (Toğa 2025).

During the 12-day war alone, Iranian authorities detained nearly 21,000 people as “suspects,” accusing many of them of transmitting intelligence to Israel (Al Jazeera 2025, 3). Seven individuals were executed after the war on charges of espionage (Al Jazeera 2025).

The war exposed fragmentation in decision-making mechanisms, forcing Tehran to pursue greater centralization in governance. With the approval of Supreme Leader Khamenei, a “Defense Council” was established under the leadership of the president with the aim of synchronizing military, political, and economic capacities (Toğa 2025). At the same time, in the event of force majeure that could arise from the collapse of central command, executive powers were delegated to provincial governors and local units of the IRGC (Golkar 2025).

Map 2. Iran’s known defense infrastructure.

The post-war period has also been marked by a mass campaign against Afghan migrants. Nearly half a million Afghans were rapidly deported (Al Jazeera 2025). Although it has been claimed that intelligence-related materials were discovered on migrants’ phones during police checks (Al Jazeera 2025), it is impossible to verify these allegations. This campaign may also be linked to efforts to ease the burden of the economic crisis and to the collapse of Iran’s plans in Syria.

Although President Masoud Pezeshkian’s government proposed certain social relaxations in order to calm society after the war, the IRGC and hardline factions have shown strong resistance to these measures (Motamedi 2025). As a result, a deep confrontation persists within the state between advocates of “renewal” and proponents of “conservatism” (Motamedi 2025).

After the war, Iran has sought not only to remain on the defensive but also to shift toward a strategy of confronting threats beyond its borders (Toğa 2025). The heavy blows suffered by Hezbollah and Hamas exposed the fragility of Iran’s proxy strategy, prompting coordination meetings in Baghdad in July 2025 with the participation of representatives of Hezbollah, Hamas, the Houthis, and Hashd al-Shaabi (Toğa 2025). The aim was to restore critical logistical arteries as much as possible (Toğa 2025).

Having witnessed during the war the risks associated with dependence on Western technologies, Iran has accelerated its relations with China and Russia. In particular, the transition process to China’s BeiDou navigation system as an alternative to the US-controlled GPS system has been expedited (Toğa 2025). At the same time, the procurement of new air defense systems (including claims related to the HQ-9B) and military exercises have come onto the agenda (Toğa 2025).

In order to compensate for the erosion of its revolutionary legitimacy, the regime has begun to combine religious rhetoric with Iranian nationalism. Linking ancient myths such as Arash Kamangir to the missile program is intended to construct a nationalist narrative aimed at uniting society against an external enemy (Golkar 2025). This narrative construction may also be understood as a counter-strategy against the growing influence among Persian nationalists of the successors of a military-usurper regime bearing the “Pahlavi” surname—an influence that, despite being exposed in international media, is not uniformly accepted in domestic public opinion.

What comes next?

It can be expected that the factors triggering the Iranian protests—which have been ongoing for several days and accompanied by deaths and arrests—will persist regardless of whether the protests themselves continue. Iran is experiencing a deep financial crisis, as well as a water crisis and an energy crisis stemming from water scarcity. Iran’s financial crisis is closely linked both to domestic political credibility and to its international political position. Practice suggests that political determinants have a colossal impact on Iran’s economy. Even an increase in oil revenues cannot save the Iranian rial, as the regime is deprived of the tools necessary to regulate the exchange rate. In addition, Iran–Israel and Iran–US relations remain sharply confrontational, and a new conflict cannot be ruled out. In this context, it is possible to consider what lies ahead through several scenarios. Before doing so, however, it should be noted that any scenario entails high risks for the Iranian regime:

1. If a new confrontation occurs:

A new confrontation could push Iran into an even deeper crisis. Although there have been attempts to enhance Iran’s military capabilities through cooperation with China after the 12-day war, it is difficult to assess the extent to which the missile/UAV system has been restored. Moreover, the 12-day war clearly demonstrated that Iran’s air defense system is significantly outdated. Regardless of the fate of its adversaries, this scenario could trigger irreversible processes for Iran at the current stage.

However, it is difficult to predict how the deepening economic crisis under such a confrontation would translate sociologically. In this scenario, the regime could quite easily reinforce its image as a victim by relying on Shiite narratives, thereby increasing public support.

2. If no new confrontation occurs:

Despite Trump’s statements about “supporting protesters,” it is debatable whether Israel, the US ally, is prepared for a new conflict. Although Iran’s attacks during the 12-day war had minimal impact on Israel, they were nevertheless able to create an atmosphere of fear within Israeli society. Under such circumstances, it can be argued that the Iranian regime would be unable to reinforce its victim image; on the contrary, support for its proxies has increasingly become a target of criticism by protesters. Nevertheless, the growing authoritarian consolidation and control, combined with the weak organizational structure of the protests, may negatively affect the prospects of a revolutionary scenario.

3. Restoration of diplomacy with the West:

This is the most desirable scenario for Iran. Based on current data, only such a scenario would make it possible to reduce both Iran’s security concerns and its economic crisis. However, this scenario is currently the least realistic, given both domestic and external factors. Under conditions of deepening authoritarian consolidation and the growing influence of a conservative military elite in governance, Iran’s opening toward diplomacy appears unlikely. It should also be added that Israel has adopted a much tougher stance toward Iran.

4. Regional cooperation:

In the post-war period, Iran has made efforts to improve relations with neighboring states. This may be aimed both at achieving economic resilience and at limiting the maneuvering space of adversaries in the event of a new confrontation. Although this scenario is already partially unfolding, it will not provide Iran with quick solutions for exiting the crisis.

Conclusion

This analysis addressed the questions: “What are the political and economic factors that trigger discontent in Iran? Given these political and economic parameters, what are Iran’s continuity scenarios?” Several conclusions were reached. The article demonstrated that the depreciation of the official exchange rate—which directly motivates protests—is linked to external political factors. Even in situations where oil revenues increase, Iran’s ability to regulate its domestic economy remains limited. Years of accumulated public distrust, alongside structural factors, further deepen Iran’s crisis.

The impact of the ongoing consequences of the confrontation with Israel on the crisis is undeniable. In addition, the effects of the “snapback” mechanism activated by the E3 group can be expected to be unprecedented. Against the backdrop of the structural constraints outlined above, the likelihood that Iran will be able to mitigate the effects of the crisis is extremely low. In short, ceteris paribus, everything is moving in a much worse direction. Climate change, water scarcity, and the energy crisis add further strain to the economic crisis.

The humanitarian consequences of the deepening crisis are likely to be severe, with the potential to generate political outcomes, including a collapse scenario. Understanding the humanitarian, political, and regional impacts of this deepening crisis will require sustained temporal observation.

References:

Aksüt, Fahri. 2020. “Timeline: US-Iran Tension Since Collapse of Nuke Deal.” Anadolu Agency, January 8, 2020. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/timeline-us-iran-tension-since-collapse-of-nuke-deal/1697001.

Al Jazeera. 2025. “Iran Says It Arrested 21,000 ‘Suspects’ During 12-Day War With Israel-US.” Al Jazeera, August 12, 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/8/12/iran-says-it-arrested-21000-suspects-during-12-day-war-with-israel-us.

BBC. 2019. “Six Charts That Show How Hard US Sanctions Have Hit Iran.” BBC News, December 9, 2019.https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-48119109.

BBC. 2026. “Deadly clashes between protesters and security forces as Iran unrest grows

” BBC News, January 2026. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c36810pkz96o.

Bonbast. 2026. “(USD/IRR) US Dollar to Rial Rate – Graph/Chart.” Bonbast.com. Accessed January 2026. https://bonbast.com/graph. Bonbast provides live and historical free-market exchange rates for the Iranian rial (in tomans) and charts showing sell, buy, average, maximum, and minimum values.

Council of the European Union. 2025a. Timeline of Measures Targeting Nuclear Proliferation Activities — Sanctions Against Iran. Accessed December 2025. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions-against-iran/timeline-measures-targeting-nuclear-proliferation-activities/#:~:text=Council%20Regulation%20(EU)%202015/,Plan%20of%20Action%20(JCPOA).

Council of the European Union. 2025b. “Iran Sanctions Snapback: Council Reimposes Restrictive Measures.” Press release, September 29, 2025. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/09/29/iran-sanctions-snapback-council-reimposes-restrictive-measures/.

Golkar, Saeid. 2025. “Humiliation and Transformation: The Islamic Republic After the 12-Day War.” Foreign Policy Research Institute, October 30, 2025. https://www.fpri.org/article/2025/10/humiliation-and-transformation-the-islamic-republic-after-the-12-day-war/.

Hanna, Andrew. 2021. “Sanctions 5: Trump’s ‘Maximum Pressure’ Targets.” The Iran Primer (United States Institute of Peace), March 3, 2021. https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2021/mar/03/sanctions-5-trumps-maximum-pressure-targets.

Motamedi, Maziar. 2025. “Iran Grapples Over Social Freedoms After War With Israel.” Al Jazeera, November 1, 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/11/1/iran-grapples-over-social-freedoms-after-war-with-israel.

Tasnim News Agency. 2026. قالیباف: مراکز و نیروهای آمریکا در منطقه هدف مشروع ما هستند [Qalibaf: U.S. Centers and Forces in the Region Are a Legitimate Target]. Tasnim News, January 2, 2026. https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/10/12/3486369/%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%84%DB%8C%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%81-%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%A7%DA%A9%D8%B2-%D9%88-%D9%86%DB%8C%D8%B1%D9%88%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D8%A2%D9%85%D8%B1%DB%8C%DA%A9%D8%A7-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D9%85%D9%86%D8%B7%D9%82%D9%87-%D9%87%D8%AF%D9%81-%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B9-%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA.

Toğa, Oral. 2025. 12 Günlük Çatışma Sonrası İran: Proaktif Güvenlik Doktrinine Geçiş. İRAM Center, September 12, 2025. https://www.iramcenter.org/uploads/files/12_Gu%CC%88nlu%CC%88k_C%CC%A7atis%CC%A7ma_Sonrasi_I%CC%87ran_Proaktif_Gu%CC%88venlik_Doktrinine_Gec%CC%A7is%CC%A7.pdf.

TradeIMEX. 2025. Iran Oil Export Data by Country and Production Stats. TradeIMEX blog. Accessed January 2026. https://www.tradeimex.in/blogs/iran-oil-export-data-by-country-and-production-stats.

Trump, Donald J. 2026. Truth Social, January 2, 2026. In this post, Trump warned that if Iranian authorities “shoot and violently kill peaceful protesters, which is their custom,” the “United States of America will come to their rescue” and asserted the U.S. was “locked and loaded and ready to go. https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump/115824439366264186.

Iran Intl. 2026. “ادامه بازداشتها در ایران؛ ههنگاو: هویت بیش از ۹۰ نفر را شناسایی کردهایم [Continued Arrests in Iran; Hengaw: Identities of More Than 90 People Identified].” Iran Intl, January 2, 2026. https://www.iranintl.com/202601020751.

Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA). 2026a. “سخنگوی پلیس: اعتراضات اخیر ماهیت اقتصادی و مدنی داشت/ اجازه سوءاستفاده و ناامنی داده نشد [Police Spokesperson: Recent Protests Were Economic and Civil in Nature; No Permission for Exploitation and Insecurity].” IRNA, January 2, 2026. https://www.irna.ir/news/86043034/%D8%B3%D8%AE%D9%86%DA%AF%D9%88%DB%8C-%D9%BE%D9%84%DB%8C%D8%B3-%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B6%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D8%AE%DB%8C%D8%B1-%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%87%DB%8C%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%AA%D8%B5%D8%A7%D8%AF%DB%8C-%D9%88-%D9%85%D8%AF%D9%86%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B4%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D8%AC%D8%A7%D8%B2%D9%87-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%A1%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%87.

Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA). 2026b. “Iran Arrests 14 Members of an Organized Explosives Production Network in Alborz Province.” IRNA English, January 2, 2026. https://en.irna.ir/news/86042590/Iran-arrests-14-members-of-an-organized-explosives-production.

UK Government. 2025. E3 Joint Statement on Iran: Activation of the Snapback. GOV.UK, September 29, 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/e3-joint-statement-on-iran-activation-of-the-snapback.

Yildiz, Guney. 2026. “Iran Rial Crashes to 1.44 Million; First Death Confirmed in Kuhdasht as Bazaar Breaks with the Regime.” Forbes, January 1, 2026. https://www.forbes.com/sites/guneyyildiz/2026/01/01/iran-rial-crashes-to-144-million-first-death-confirmed-in-kuhdasht-as-bazaar-breaks-with-the-regime/.