This analysis is part of the KHAR Center's project “Authoritarian Regimes and Transregional Influence Mechanisms”

Part II

Click here to read the first part of the article.

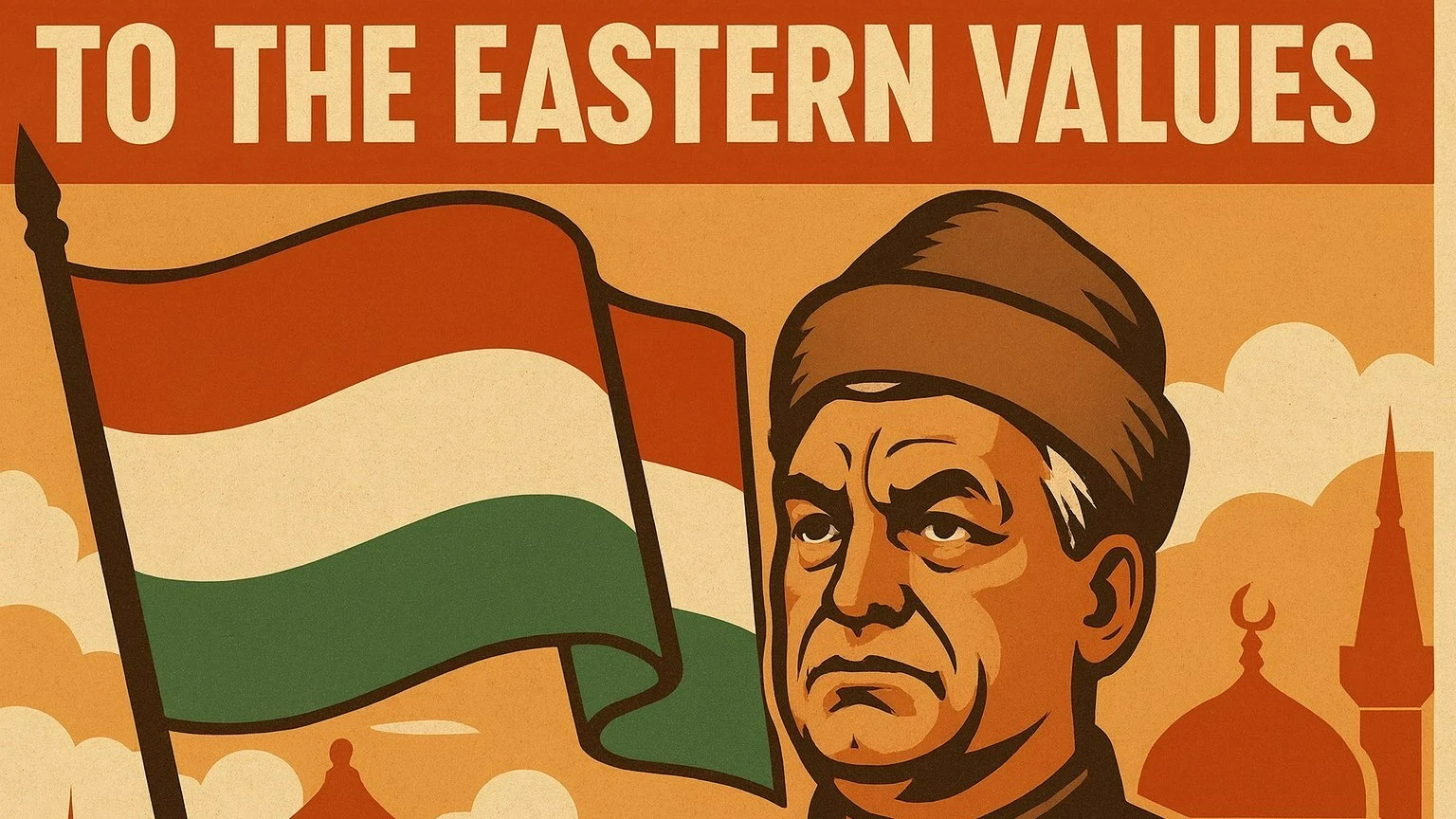

Orbanization: An Eastern Model in the West

The Hungarian model under Viktor Orbán has gone far beyond being a domestic political matter. It has become the name for a systematic sabotage strategy built within the European Union—an integration plan of authoritarian regimes under the guise of illiberalism.

"Orbanization" is now a political phenomenon—a trend of establishing islands of authoritarianism within post-communist European states under the economic and military umbrella of the EU and NATO. It is a political pattern that legitimizes the dismantling of institutions in the name of the people, pursues Eastern politics with Western resources, sabotages Western liberal integration models, and exploits veto power and crises for political gain.

This section of KHAR Center’s research explores the structural transformation of Hungary into an authoritarian state under Orbán’s rule, the fractures it has created within the EU, the alliances forged with authoritarian regimes in the East, and the nuances behind Hungary’s deliberate dependency on Russia and China.

What Is “Orbanization”?

The term "Orbanization" is used particularly in the works of scholars like Jan-Werner Müller and Bálint Magyar to describe the diffusion capacity of the Hungarian example. The model is built on three main pillars:

- Institutional Takeover – Bringing the judiciary, media, and education system under political control;

- Populist Discourse Engineering – Framing narratives through dichotomies like “people vs. elites” and “foreign forces vs. national will”;

- Illiberal Internationalism – Forming tactical alliances with other sovereigntist leaders.

Unlike its neighbors, Hungary did not adopt a new constitution during its transition from communism to democracy. Instead, it chose to amend the 1949 constitution. Few foresaw that provisions such as the “two-thirds majority in parliament” would ever become relevant—until 2010, when Orbán’s party won 263 of the 386 parliamentary seats.

Orbán used this opportunity to strengthen and prolong his regime with great determination. He rewrote nearly all laws—from the electoral code to the Constitutional Court, from media to civil society institutions, from foreign policy to the economy—effectively designing a new system and seizing all state institutions (KHAR Center, 2025).

This transformation allowed him to evolve from a spoiled partner into a saboteur within the European Union.

Opening to the East

Cracks in Orbán's relationship with the West emerged after the 2008 global financial crisis. From 2009 onwards, Orbán increasingly claimed that the Western system was collapsing and began to call for an eastward orientation (Lendvai, 2017a).

At the Hungarian Permanent Conference on September 5, 2010, he declared his intent to shift the country’s economic direction: “The wind blows from the East in the world economy, yet we stand under the Western flag watching it.” In a 2011 speech in Paris, he named this approach “Opening to the East.” He stated, “We will continue the Eastern Opening we launched a year ago in our economic relations. China, South Korea, and Japan will increasingly become valuable economic and trade partners for Hungary” (HGV, 2011).

Under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, a formal “Eastern Opening” initiative was launched, establishing Hungarian Trade Houses in Moscow, Beijing, Astana, and Abu Dhabi. Though warm signals were sent toward Russia and China, the policy did not yield tangible economic results between 2010 and 2015. In fact, trade with Eastern countries declined. Starting in 2014, Orbán gradually dropped the term “Eastern Opening” from his vocabulary (The Orange Files, 2018), though this did not mean he abandoned his anti-Western orientation.

Illiberalism

Emboldened by the system he had built and by society’s silence, Orbán publicly declared on July 26, 2014, in Baile Tușnad, Romania, that Hungary would depart from liberal democracy. He argued that the liberal democratic system existing between 1990 and 2010 had hindered the government’s ability to act in the national interest, had alienated ethnic Hungarians abroad from the state, failed to protect public resources, and couldn’t rescue the country from debt.

Emphasizing that the world’s most successful countries were not liberal democracies, Orbán cited China, Singapore, India, Russia, and Turkey as models. According to him, Hungary must distance itself from Western Europe's dogmas and ideologies and find its own path (OSW, 2014).

Tensions with the European Union

Although Hungary is a member of the European Union, its relations with the bloc have sharply deteriorated under Orbán’s leadership. The friction has primarily concerned rule of law, judicial independence, media pluralism, and treatment of civil society. The European Commission has initiated multiple legal proceedings against Hungary, including Article 7 procedures—the EU’s most severe institutional mechanism against a member state (AA, May 2025).

Orbán’s argument is simple: Brussels violates national sovereignty and seeks to impose liberal ideological hegemony. The Hungarian government treats the EU merely as an economic platform and rejects value-based integration. In foreign policy, Orbán increasingly aligns himself not with the European club, but with the authoritarian East—Russia, China, Turkey, and Pakistan.

This stance is especially evident in Hungary’s migration policy, which remains uncompromising despite EU sanctions. In 2024, the European Court of Justice ruled that Hungary had violated international law by obstructing asylum procedures, imposing a €200 million fine and an additional €1 million daily penalty. Yet in 2024 alone, Hungary deported 5,713 migrants (AIDA, 2025).

The Ukraine War and Strategic Sabotage

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine, Orbán has emerged as the leading EU voice opposing sanctions against Russia. His sabotage attempts have been mitigated by the EU either meeting his demands or threatening financial penalties.

In June 2022, the European Council granted candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova—a move Orbán opposed, citing the alleged violation of rights of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine. During the December 2023 summit, he temporarily left the room during the Ukraine and Moldova discussions, allowing the vote to proceed. In June 2023, he accepted opening talks before Hungary assumed the EU presidency on July 1.

In late 2022, Orbán threatened to veto an €18 billion aid package for Ukraine, withdrawing only after the EU agreed to approve Hungary’s €5.8 billion recovery plan and reduced a planned €7.5 billion freeze to €6.3 billion (Reuters, 2022). Similarly, in December 2023, Orbán blocked a €50 billion Ukraine support package, again citing minority rights. Yet in February 2024, under threat of losing €20 billion in EU funding and having Hungary's voting rights suspended, he did not veto the package (BBC Türkçe, 2024).

Hungary’s EU Presidency and Further Obstruction

When Hungary assumed the rotating EU presidency in spring 2024, it announced that it would not open any of the 35 negotiation chapters with Ukraine. On July 1, Hungary officially took over the EU Council presidency. Just four days later, Orbán met with Vladimir Putin in Moscow. He again signaled vetoes on future sanctions, claiming that while the EU is pro-war, Hungary seeks peace (AP, 2024).

Orbán’s veto threats have been emboldened by Donald Trump’s return to power in the U.S. During discussions on the EU’s 16th sanctions package against Russia in January 2025, Orbán openly stated he was pulling the handbrake so EU leaders would realize that continued sanctions were unsustainable (Euronews, January 2025). After three failed summits, the EU persuaded him to relent by removing three individuals from the sanctions list and promising greater cooperation on energy infrastructure.

In March 2025, shortly after the U.S. announced it would stop military aid to Ukraine, EU leaders held an emergency meeting and pledged increased support for Ukraine—one of the strongest demonstrations of military solidarity within the bloc. Orbán refused to participate, saying Hungary would not join a "pro-war" European army. The decision was adopted in his absence with 26 votes. Orbán retorted: “We are not the ones isolated. The EU has isolated itself—from the U.S. due to trade wars, from China due to trade tensions, and from Russia due to sanctions” (Euronews, March 2025).

In June, Hungary vetoed the opening of EU membership negotiations with Ukraine. He justified the move with a dubious referendum held on March 30—conducted via electronic and postal voting—which claimed that 95% of Hungarians opposed Ukraine's EU accession talks. Observers believe this veto, along with his December 2023 passive stance, can be linked to Hungary’s 2026 elections. As a result, Ukraine's EU accession process will likely remain under threat for at least 10 months (The New Union, June 2025).

In the same month, Hungary—alongside Slovakia—blocked the EU’s 18th sanctions package targeting Russian energy. Their justification was that the sanctions would harm Hungary’s economy, delaying the package’s approval by a month.

Manipulating Dependency on Russia

Orbán not only maintains Hungary’s dependency on Russian oil and gas but skillfully uses this dependency as a tactical advantage against the EU. Through these energy ties, he claims to be preserving Hungary’s “strategic autonomy” (Varga, 2021). At first glance, this argument appears valid. Based on current figures, Hungary imports 86% of its crude oil from Russia. In 2022, the year Russia invaded Ukraine, that figure stood at 61% (Politico, May 2025).

In 2023, Hungary obtained 85% of its gas from Russia (Radio Svoboda, 2023). Although this figure slightly declined after 2023, it is estimated to still hover around 85% in 2025. A large portion of this gas is delivered via the “TurkStream” pipeline through Turkey.

Hungary’s nuclear energy is also entirely supplied by Russia. The fuel for the Paks-1 Nuclear Power Plant—which generates 48% of the country's electricity—is provided wholly by Rosatom.

Hungary is currently constructing the Paks-2 Nuclear Power Plant in cooperation with Russia. A contract between Hungary and Russia was signed in 2014, stipulating that 80% of the plant’s financing would come through a Rosatom loan (Nucnet, May 2025). In 2022, the construction of the two planned reactors received official approval. Work began in 2024 but was halted due to a wall collapse, only to resume again in June this year. Like Paks-1, all aspects of the project—from technology to fuel—are provided by Russia. It’s worth noting that the construction of Paks-2 was entrusted to the company of Orbán’s childhood friend and Hungary’s richest oligarch, Lőrinc Mészáros (Politico, 2024).

In this context, Hungary’s dependency on Russian energy is a fact, and Orbán masterfully exploits it to blackmail the West, extract concessions from the EU, and manipulate his domestic electorate.

Yet the deeper truth lies in the details—there is a wealth of credible and well-substantiated research showing that Hungary’s dependency on Russian energy is not a necessity. According to a joint report by the Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD) and the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), the EU’s 2022 decision to grant Hungary (as well as Slovakia and the Czech Republic) time and immunity from sanctions to reduce their reliance on Russian energy had the opposite effect. Instead, Hungary (and Slovakia) increased their dependency on Russian energy (CSD, May 2025a).

The report asserts that there are no technical or structural barriers to these countries breaking free from Russian crude oil dependence; the only barrier is political will.

This argument is supported by the example of the Czech Republic. By effectively using the EU’s grace period, the Czech Republic fully eliminated its 60-year dependency on Moscow by 2025. It did not renew its gas contracts in 2022, and imports dropped to nearly zero by 2023. In 2024, more than 40% of the country’s oil still came through the Druzhba pipeline, but to align with the EU’s joint stance, the Czech Republic accelerated diversification and stopped all oil imports from Russia by March 2025. The country now imports oil via the Transalpine Pipeline (TAL), connecting Italy to Germany, investing €60 million in infrastructure. It plans to import nearly 8 million tons of oil annually—enough to meet national needs (Energynews, April 2025).

Hungary (and Slovakia), on the other hand, have shown little interest in using the Adria pipeline via Croatia as an alternative for gas imports. They are similarly reluctant to explore LNG terminals such as Krk (Croatia) and Klaipeda (Lithuania), or alternative routes provided under the EU’s REPowerEU strategy, including renewables (CSD, May 2025b).

According to the CSD report, although Hungary’s national oil and gas company MOL is capable of refining imported crude oil and there is ample gas supply from countries like the U.S. and Qatar in Central Europe, Budapest seems uninterested. On the contrary, thanks to lobbying to maintain Russian energy dependency and exploiting loopholes in EU law, Hungary earns hundreds of millions of dollars. According to CREA energy expert Luke Wikken, the Orbán government earned over $500 million in tax revenue from transferring Russian oil to cover budget deficits (Politico, May 2025).

Attila Holoda, a former executive at MOL, noted that all of Hungary’s storage facilities are full and that the country has purchased 2.5 times more gas than its annual need—pointing to how the Orbán government has commodified the “gas dependency” card (Balkan Insight, 2024). By acting as a regional gas hub thanks to Russian imports, Hungary profits both materially and politically through sales to neighboring countries.

China: The Assembly Plant

China initially engaged with Hungary through the 16+1 cooperation framework for Central and Eastern Europe. These ties deepened through Orbán’s “Eastern Opening” strategy. Unlike other European countries, Hungary does not approach Chinese investment with suspicion. On the contrary, bilateral ties have grown to the extent that Hungary is now seen as China’s key foothold within the EU. Some reports even refer to Hungary as “China’s assembly plant” (Gizinska and Uznanska, 2024a).

According to official statements, Hungary is China’s third-largest trade partner in Central and Eastern Europe, and China is Hungary’s largest trade partner outside the EU. In 2023, bilateral trade volume increased by 73% compared to 2013, reaching $14.52 billion. In 2023, Chinese direct investment in Hungary exceeded the combined investment of France and Germany. Chinese FDI into Hungary that year amounted to $8.12 billion—58% of all foreign investment into the country (China Briefing, 2024).

During President Xi Jinping’s 2024 state visit to Hungary, the two countries signed a “cooperation under all conditions” agreement to mark a new era in their relations. This strategic partnership aims to expand cooperation in multiple fields, including the nuclear industry (GOV CN, 2024).

Since 2015, Hungary has been an active participant in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and was the first EU member to join the project among its 150 partners. The Belgrade–Budapest railway, a key part of the BRI corridor from Piraeus (Greece) to Duisburg (Germany), is being built with a $2 billion Chinese loan. The Hungarian portion is being constructed by a company owned by Orbán’s childhood friend, Lőrinc Mészáros (Intellinews, 2019). Despite safety concerns—like the 16 deaths caused by a station collapse in Novi Sad on the Serbian side—the Orbán government remains firmly committed to the project (GIS Reports, June 2025a).

However, delays on the Hungarian side—despite the Serbian section being completed three years ago—suggest that relations with China are not entirely smooth. Some sources claim that Xi Jinping pressured Orbán last year to resolve technical issues and delays that are hindering the project’s progress within the EU (Vsquare, 2023).

Previously, China also planned to fund the east–west V0 railway line and the airport–city high-speed rail in Budapest, originally intended to be built with a $2 billion Russian loan. But both projects were shelved due to public protests.

Thanks to the preferential treatment it receives in energy sanctions, Hungary has become a low-cost and stable market in the heart of Europe. Battery factories from Japan, South Korea, and China are relocating to Budapest.

Chinese company CATL’s $7.3 billion investment in a battery plant in Debrecen for BMW’s electric vehicle production is the largest investment in Hungarian history (Belt and Road Portal, 2024). BYD relocated its European headquarters from the Netherlands to Hungary. Industrial giants like EVE Energy and XINWANDA opened plants in Hungary. Huawei established its European Supply Center in Pécs, and after Hungary refused to join Trump’s “Clean Network” initiative, the company opened a Research and Development Center in Budapest.

Despite U.S. protests and warnings about ties to Chinese intelligence, Hungarian telecom company 4iG signed a strategic contract with Huawei for cloud and AI services—another example of how deep Hungary’s ties with China have become.

Thanks to these relations, Hungary is now the world’s fourth-largest producer of lithium-ion batteries and is expected to rise to second place by 2031 (Gizinska and Uznanska, 2024b).

Hungary has shown interest in Huawei’s AI-based facial recognition system used in Belgrade since 2019. In 2023, an agreement between the interior ministries of both countries granted Chinese police joint patrol rights in Budapest’s Chinatown and tourist areas (GIS Report, June 2025b).

Despite EU objections and assessments that such patrols pose a serious security threat and represent a backdoor for foreign interference (Reuters, 2024), the Orbán government ignored these warnings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Hungary was the first European buyer of Chinese vaccines and has also replaced pro-Western NGOs and educational institutions with Chinese alternatives (Telex, 2024).

Confucius Institutes affiliated with China’s Ministry of Education operate at universities in Budapest, Szeged, Miskolc, and Debrecen. Pécs offers Chinese medicine courses. Since 2017, Budapest has hosted the only European office of China’s Academy of Social Sciences through the China-CEE Institute.

In 2021, Hungary signed a contract with China’s Fudan University to build a campus in Budapest. But the project sparked fierce protests due to its lack of transparency and the plan to build it on a site previously earmarked for student housing. Opposition from the Budapest municipality forced the project off the agenda (RFE/RL, 2021).

Orbán doesn’t merely deepen ties with China—he acts as its most loyal defender in Europe. Between 2016 and 2022, Hungary used its veto powers six times to block EU Council resolutions condemning China. In December 2023, Hungary also refused to sign an EU document aimed at protecting the wind energy industry from unfair competition by Chinese manufacturers (Gizinska and Uznanska, 2024c).

Ideological Brotherhood with Turkey and Central Asia

The Orbán government also pursues an active policy of cooperation with Turkic states, justifying these relationships within the framework of “cultural-historical brotherhood.” However, as with other authoritarian and opaque partnerships, Hungary’s relationship with Turkey is not based on principles, but rather on pragmatic authoritarian conservatism, nationalist slogans, and political opportunism aimed at consolidating power.

Like his rapprochement with Russia, Orbán's closer ties with Turkey began in the early 2010s. Both Orbán and Erdoğan criticize the “double standards and hegemonic behavior” of leading Western states within the EU and NATO, and present integration into a multipolar world as an alternative path (Gábor Scheiring, 2024). They both emphasize sovereignty, adopt a selective approach to Western institutions, and rule through authoritarian governance based on a strong leader model.

One key area connecting Turkey and Hungary is migration policy. During the 2015 migration crisis, Orbán openly supported Turkey’s role as Europe’s “border guard” and presented Erdoğan as a “designated strategic partner” for European security (Hungary Today, 2021).

While Orbán says he supports Turkey’s accession to the EU, he adds that this would only be possible within “a new European order that recognizes cultural differences” (Lendvai, 2017b). Hungary’s 2018 accession to the Organization of Turkic States (as an observer) can also be more realistically interpreted within the context of mutual interests with Erdoğan (TDT, 2022).

Central Asian countries, particularly Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, are also key partners in Hungary’s Eurasian strategy. Within the EU, this strategy is interpreted as Orbán’s “diplomacy of ideological alternatives.”

The Visegrád Group and “Illiberal Internationalism”

One of the pillars of Orbán’s regional foreign policy is the Visegrád Group (V4 – Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary). Especially during the migration crisis, this platform became a shared space for opposing Western Europe’s liberal policies. Orbán built what might be called “illiberal internationalism” here—forming tactical alliances with similar authoritarian or sovereigntist leaders and using these alliances as leverage within the EU.

But cracks have emerged within the group. Governments in Slovakia and the Czech Republic have distanced themselves from Orbán's line and adopted migration policies more in line with EU standards. As a result, Hungary has focused more on bilateral coordination with Poland.

The group is also divided on relations with Russia and military aid to Ukraine. While Orbán and Slovakia’s Fico oppose sanctions on Russia and military support for Ukraine, Poland and the Czech Republic align with the EU’s joint stance.

In terms of democracy and the rule of law, Slovakia under Fico has moved closer to Orbán’s model, while Poland has also faced criticism recently. However, both Slovakia and Poland are not as obstinate in EU negotiations as Orbán. Despite this, after political shifts in Slovakia and Poland, the V4 remains a symbolic platform for Orbán to internationalize and legitimize his model.

The Common Value Uniting Authoritarians: The Desire for Unchecked Power

At the root of Orbán’s “love for the East” and anti-Western stance lies, undoubtedly, an insatiable desire for unlimited power. His opposition to liberalism, disdain for intellectualism stemming from personal inferiority complexes, reliance on a “strong leader” cult, intolerance for dissent, and legitimization of authoritarianism under the banners of “patriotism” and nationalism are the core elements linking him to the club of authoritarians.

In a typical European democracy, a chameleon-like ideologue and unprincipled authoritarian like Orbán could never rise to power. Thus, to fulfill his ambitions for leadership and grandeur, he seeks affinity with authoritarian regimes like Russia, China, and Turkey, and with leaders who resemble him.

These regimes provide sustenance for Orbán’s own authoritarian system. Through the control mechanisms he has constructed, he manipulates the public with promises of “cheap gas,” “electric vehicles and parts,” “Turkic heritage and shared history,” and “family and moral values”—yet the public seldom questions why these “values” only enrich Orbán and his inner circle.

John O’Sullivan, Margaret Thatcher’s former advisor and founder of the Danube Institute, once said Orbán is a misunderstood pirate provocateur:

“He is intellectually adventurous. He gets bored sticking to one political line every day. He wants to discover new ideas. In doing so, he’s willing to take some risks. He loves improvisation and speculates in public.” (VOA, 2016)

Conclusion

This analysis has shown that through the system Orbán has built domestically and his strategy of blackmail and sabotage within the European Union, he has evolved from being a mere problem into a full-blown threat to the Union. Hungary is openly implementing all the elements of authoritarianism: delaying sanctions against Russia, opposing common EU positions on human rights in China, and obstructing financial and military aid to Ukraine.

The legal loopholes in the EU’s decision-making mechanisms have emboldened Orbán further, pushing Brussels toward more concessions. This weakens the EU’s ability to respond in a timely and effective manner and undermines its global credibility and reputation.

The argument of this analysis concludes that Orbán represents an internal threat to the European Union (Estonian Security & Defence Working Group, July 2025).

Orbanization is not just an internal democratic problem for the EU—it is a strategic threat. To contain this trend, the EU must strengthen its institutional resilience, ensure internal solidarity, and uphold normative principles.

The Hungarian experience shows that elections and constitutions alone are not sufficient for post-transition regimes to become stable democracies. Democratic consolidation also requires a normative political culture, a strong and pluralistic civil society, media freedom, and systems of institutional checks and balances. Without these elements, as the Hungarian case demonstrates, transitions may result in a “reverse transition.”

Despite all these tendencies, resistance among Hungary’s liberal and democratic forces has not entirely faded. Discontent is rising among urban, young, and educated voters. While the united opposition in the 2022 elections failed to achieve the desired outcome, such attempts still reveal the existence of potential alternatives to illiberal hegemony.

Two main scenarios are considered for the post-Orbán era:

- Natural leadership change and stable succession within FIDESZ:

This would ensure institutional continuity and regime stability. The authoritarian structure would adapt through superficial reforms, while the fundamental power balance remains intact. - Political crisis and a wave of social unrest:

Rising economic hardship and institutional collapse could trigger large-scale democratic reform—not just leadership change, but structural regime dismantling.

Both scenarios highlight Hungary’s political trajectory as both a warning and an empirical case for democracy theory—especially in illustrating how democratic backsliding becomes normalized and which socio-political mechanisms provoke resistance.

References:

Khar Center. İyun 2025. Macarıstanın siyasi sistemi. https://kharcenter.com/nesrler/macaristanin-siyasi-sistemi

Lendvai, Paul. 2017. Orbán: Hungary's Strongman. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190874865.

Index.hu. 2010. Orbán: Keleti szél fúj. https://index.hu/belfold/2010/11/05/orban_keleti_szel_fuj/?token=0117ce975ed215bb8efb57de4e13d2b3.

HVG. 2011. “Orbán: ‘Még nagyon sok gonddal is szembe kell néznünk.’” https://hvg.hu/itthon/20110525_orban_keleti_nyitas_oecd.

The Orange Files. 2018. “Eastern Opening.” https://theorangefiles.hu/eastern-opening/?utm.

OSW (Centre for Eastern Studies). 2014. “Orbán’s Anti-Liberal Manifesto.” https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2014-08-06/orbans-anti-liberal-manifesto?utm.

Anadolu Agency. May 2025. EU to maintain Article 7 procedure over Hungary’s rule of law breaches. 'https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/eu-to-maintain-article-7-procedure-over-hungarys-rule-of-law-breaches/3581462?utm

AİDA, may 2025. https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/AIDA-HU_2024-Update.pdf

BBC Türkçe. 2024. Avrupa Birliği, Ukrayna ve Moldova ile tam üyelik müzakerelerine resmen başladı: Süreç nasıl işleyecek?

https://www.bbc.com/turkce/articles/cv22g6yx7vpo

Reuters. 2022. Hungary vetoes EU aid for Ukraine, bloc delays decision on funds for Budapest

BBC Türkçe. 2024. Macaristan, AB zirvesinde Ukrayna’ya 50 milyar euroluk yardım paketini onayladı: Başbakan Orban vetoyu neden kaldırdı?

https://www.bbc.com/turkce/articles/cd17n24qz0no

AP. 2024. Hungary”s Orban meets Putin for talks in Moscow in a rare visit by a European leader

Euronews. Yanvar 2025. Playing with fire': Orbán's sanctions veto threat puts Brussels on edge

Euronews. Mart 2025. EU leaders' summit ends with Orbán vetoing conclusions on Ukraine

The News Union. İyun 2025. Orbán’s Hungary continues to veto Ukraine’s EU accession talks, now via a—legally non-binding—referendum

https://newunionpost.eu/2025/06/27/hungary-referendum-ukraine-accession/?utm_

Politico. May 2025. “Hungary and Slovakia Can Quit Russian Energy, Report Finds.https://www.politico.eu/article/hungary-slovakia-quit-russia-energy-crea-report/?utm.

Radio Svoboda. 2023. Венгрия продлила соглашение с Россией о дополнительных поставках газа

a/vengriya-prodlila-soglashenie-s-rossiey-o-dopolniteljnyh-postavkah-gaza/32359210.html.

NucNet. May 2025. “US Has Lifted Sanctions on Hungary’s Paks II Nuclear Project, Says Foreign Minister.” https://www.nucnet.org/news/us-has-lifted-sanctions-on-hungary-s-paks-ii-nuclear-project-says-foreign-minister-6-1-2025?utm.

Politico. 2024. “The Kremlin’s Growing Influence in Orbán’s Hungary.” https://www.politico.eu/article/kremlin-russia-hungary-viktor-orban-oil-gazprom-media-gabor-kubatov-fidesz-party/?utm.

Centre for the Study of Democracy (CSD). May 2025 a. “The Last Mile.” https://csd.eu/publications/publication/the-last-mile/.

Energynews. Aprel 2025. The Czech Republic ends 60 years of dependency on Russian oil

https://energynews.pro/en/the-czech-republic-ends-60-years-of-dependency-on-russian-oil/?utm

Centre for the Study of Democracy (CSD). May 2025 b. “The Last Mile.” https://csd.eu/publications/publication/the-last-mile/.

Politico. May 2025. “Hungary and Slovakia Can Quit Russian Energy, Report Finds.” https://www.politico.eu/article/hungary-slovakia-quit-russia-energy-crea-report/?utm.

Balkan Insight. 2024. “Hungary Turns Itself into Hub for Russian Gas.” https://balkaninsight.com/2024/12/11/hungary-turns-itself-into-hub-for-russian-gas/?utm.

China Breifing. 2024. China-Hungary Bilateral Relations: Trade and Investment Outlook https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-hungary-bilateral-relations-trade-and-investment-outlook/?utm

GOV.CN, 2024. Full text: China-Hungary Joint Statement on the Establishment of an All-Weather Comprehensive Strategic Partnership for the New Era https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202405/10/content_WS663d3b83c6d0868f4e8e6eb0.html?utm

İntellinews, 2019. Hungarian PM Viktor Orban’s friend seals €2.3bn railway contract with Chinese firms

GİS Report. İyun 2025 a.. China’s European bridgehead https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-hungary/?utm

Vsquare, 2023. Orbán travels to Beijing, commits to Chinese rail tech

https://vsquare.org/no-7-spying-in-brussels-orban-in-china-human-trafficking-in-cee/

Belt and Road Portal. 2024. Hungarian experts expect deepening friendship with China via BRI https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/0LDOJEV5.html?utm

Reuters. 2024. EU Commission chief: Hungary's Russia, China policies pose security risk

Telex, 2024. How the Chinese Communist Party's United Front extends its influence to Hungarian Associations

RFE/Rl. 2021. New Chinese University In Hungary Puts Orban's Beijing Ties In The Spotlight

https://www.rferl.org/a/fudan-university-hungary-orban-china-ties/31236149.html

Gizinska İlona, Uznanska Paulina. 2024. China’s European bridgehead. Hungary’s dangerous relationship with Beijing

GİS Report. İyun 2025 b.. China’s European bridgehead https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-hungary/?utm

Greilinger, Georg. 2023. Hungary’s Eastern Opening Policy as a Long-TermPolitical-Economic Strategy. https://www.aies.at/download/2023/AIES-Fokus-2023-04.pdf

Gábor Scheiring, 2024. I Watched Orbán Destroy Hungary’s Democracy. Here’s My Advice for the Trump Era. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2024/11/23/trump-autocrat-elections-00191281

Hungary Today. 2021. Orbán in Turkey: Europe in Need of Allies Who Can Expand Lines of Defence

https://hungarytoday.hu/orban-turkey-migration-borders-eu-support-erdogan/?utm_

Lendvai, Paul. 2017 b. Orbán: Hungary's Strongman. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190874865.

TDT. 2022. https://www.turkicstates.org/areas-of-cooperation-detail/1-political-cooperation

Voice of America (VOA). 2016. “Hungary’s Orbán: Autocrat or Misunderstood Provocateur?”

https://www.voanews.com/a/is-hungary-orban-autocrat-or-misunderstood-provocateur/3164978.html.

Estonian Security and Defence Working Group. İyul 2025. “Strategic Saboteur: Hungary’s Entrenched Illiberalism and the Fracturing of EU Cohesion.” https://esthinktank.com/2025/07/10/strategic-saboteur-hungarys-entrenched-illiberalism-and-the-fracturing-of-eu-cohesion/?utm

.

Direkt36. 2021. “Orbán’s Eastern Opening Brings Spy Games to Budapest.” https://www.direkt36.hu/en/kemjatszmakat-hozott-budapestre-orban-kinai-nyitasa/.

Bozsó, Ágnes, and Zoltán Kovács. 2021. “Hungary to Build Budapest Campus of Chinese University with Chinese Loan.” *Euractiv*.