(This article was prepared within the framework of the KHAR Center's research on Azerbaijani authoritarianism)

✍️ Elman Fattah – Director of KHAR Center

Introduction

Azerbaijan faces a looming deep crisis between 2027 and 2035. For thirty years, the country has relied on an oil-based governance model that is now turning into a textbook example of the resource curse. The financial stability built during the oil boom is gradually eroding to critical levels. This decline is not confined to the economy—it is manifesting politically and institutionally as well. Even if the regime manages to maintain the current situation for a while longer, it is highly unlikely that it will be able to respond adequately to the upcoming shocks. Widespread repression, the abolition of politics, and the labeling of all dissent as treason indicate that the system is preparing to face the approaching difficult period using its traditional methods.

The country's current situation is increasingly defined by the inevitable reality of the post-oil era: the silent and gradual depletion of resources. The relative stability of the state budget and the appearance of "sufficient" currency reserves are deceptive. In reality, the rent is shrinking, the foundational principles of the social contract are weakening, and the authoritarian governance model’s key mechanism—the “silence in exchange for money” bargain—is rapidly losing its effectiveness. Therefore, the years 2027–2035 must not be seen as a "relatively difficult phase," but rather as a period in which the existing model can no longer sustain itself, fails to adapt to new realities, and approaches a historic crossroads.

Objective

The goal of this analysis is to uncover the nature of the depletion process that will begin in Azerbaijan between 2027 and 2035, and to assess the risks and opportunities presented by the post-oil phase within a political-analytical framework.

The analysis seeks to answer the following questions:

- Is Azerbaijan prepared for the post-oil era?

- Through which mechanisms is the current model entering a trajectory of depletion?

These questions are explored through three interconnected dimensions:

- The economic and fiscal sustainability of the energy-rent model;

- The erosion of the authoritarian social contract;

- Structural weaknesses in governance and the inability to manage crises.

The Paradox of a Wealthy Country’s Impoverished Future

Azerbaijan’s oil story is nearing its end. The observed declines in production are a painful reality. There has also been no progress in discovering new fields. Annual energy reviews by BP and country profiles by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) show that oil production in Azerbaijan peaked in the early 2010s. Since then, there has been a steady decline. Official statistics from SOCAR confirm that the ACG (Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli) bloc is in a declining production phase.

According to an analytical review prepared by the Baku Research Institute, oil production in Azerbaijan is expected to reach only 27.5 million tons in 2025. This is nearly half of the 50.5 million tons produced in 2010. The review forecasts that production will drop below 27 million tons in 2026, citing Azerbaijan’s own official socio-economic development projections up to 2030. Despite natural gas production increasing 2.5 times and exports rising more than fourfold between 2010 and 2024—and despite rising energy prices in the past three years due to the Russia-Ukraine war—Azerbaijan’s resource revenues have still significantly declined. In 2010, the government earned $19 billion through the Oil Fund and state budget, but by 2024, this had dropped by $6.5 billion to $13.5 billion. The total oil and gas revenue forecast in the 2025 consolidated budget is expected to fall below $12 billion (BRI, Nov 2025).

In parallel, reports from the World Bank and the IEA note that no major new commercial fields have been discovered recently. The current strategy focuses primarily on maximizing output from existing fields (BP, 2022; IEA, 2022; World Bank, 2024a; Minenergy, 2024). The trajectory indicates that the engine of Azerbaijan’s economy—and even the diplomatic leverage of the Aliyev regime, built on SOCAR-BP cooperation—is approaching its end. The fundamental question is no longer “How can we generate more income?” but rather “How can we manage the decline?”

For a long time, Azerbaijan’s economic development was made dependent on oil. Projects like ACG and Shah Deniz symbolized prosperity, stability, and hope for the future (president.az, 2024). But those peak periods are now behind us. Moreover, energy companies’ strategies have also shifted. Investors who once took risks are now more cautious. The primary reason is the growing appeal of renewable energy and the declining relevance of oil and gas. Major firms are no longer showing the same interest in long-term oil projects. This also means that Azerbaijan’s foreign policy, once empowered by oil diplomacy, will lose its effectiveness.

Thus, the regime’s problem will not be limited to domestic economic challenges. Its international legitimacy tool—oil diplomacy—will also lose significance.

A major risk for Azerbaijan is that Europe’s transformation of its energy policy has become irreversible. The EU’s 2030 and 2050 green energy targets are not just goals but binding legal obligations that signal declining demand for hydrocarbons (European Commission, 2021). This brings the danger of Azerbaijan losing its most important strategic customer in the export market.

While the oil and gas sector will still generate revenue for a while, its strategic importance is diminishing. Crucially, because the government has been simulating diversification rather than genuinely pursuing it, Azerbaijan lacks new economic sectors capable of meeting the demands of the post-carbon era. Over the next decade, there are no sustainable economic sectors in place to replace even half of the current oil and gas revenues. The absence of high-tech products in the export structure, complete reliance on imports for such goods, the collapse of the education system as a functioning institution, and the loss of capacity to train skilled professionals for the labor market show that the economy is utterly unprepared for the post-oil era.

During the era of large oil revenues, the government built a model of temporary social and political stability through extensive monetary emissions. That model is now nearing its end. For the first time in recent years, the next year’s budget has effectively been approved without any increase—an early sign of what’s to come.

For this reason, Azerbaijan’s economic future is locked into the narrowing opportunities of the European market.

The Illusion of the Oil Fund

Although the State Oil Fund’s financial resources appear sizable on paper, growing social demands, infrastructure expenses, import dependency, and fluctuating security costs reduce the real value of this capital (SOFAZ, 2025a). Moreover, the price of gold—comprising about a quarter of the Fund’s assets—has nearly doubled over the past three years due to global economic risks. This indicates the presence of asset bubbles in both financial and precious metals markets. As global risks ease, the capitalization of the Fund’s assets may shrink, and a portion of its reserves may inevitably be lost.

Instead of supporting a transition to a non-oil economy, the Oil Fund continues to serve as a cushion for financing the current budget. A review of the Fund’s annual budget transfers makes this situation clear (SOFAZ, 2024). This imbalance will only deepen as 2030 approaches. Yet the Fund was originally created to protect the country from future economic shocks, provide financial support to various sectors, and accumulate strategic capital for the post-oil era (SOFAZ, Mission and Objectives). In practice, however, the Fund has become the government’s purse.

It is now being used to fund social welfare packages, maintain administrative bodies, finance inefficient infrastructure projects, support populist government decisions, and cover consumption expenditures tied to imports (SOFAZ, 2025b). As oil revenues decline, budgetary demands on the Fund will increase. Consequently, as 2030 nears, the Fund is ceasing to be a safety cushion and turning into a depleting shock absorber.

The Labyrinth

The political system presents the inevitable approaching crisis as a matter of communication rather than substance. The objective here is not to propose reform plans aimed at resolving the crisis; on the contrary, it is to keep a sense of threat alive in the public consciousness. Pseudo-patriotism and militarization are designed to deceive society with fabricated dangers during the approaching socio-economic crisis. This approach reveals a core feature of Azerbaijan’s current political structures: rather than eliminating emerging problems, the system prioritizes managing how those problems are perceived by the public.

The regime attempts to conceal the fact that the looming crisis stems from structural deficiencies in the economic model, because acknowledging this would amount to admitting that the model itself has become obsolete. For this reason, the government manipulates statistics and frames harsh realities as “temporary difficulties,” thereby preventing public discussion of the inevitable crisis. At best, this tactic merely masks the severity of the crisis. As a result, what currently appears as economic volatility is, due to the exhaustion of governance capacity, setting the stage for a potential downturn to transform into a deep and systemic crisis.

The figures promoted as growth in the non-oil sector are hollow. Diversification exists only at the level of discourse. This exposes the widest gap in Azerbaijan’s economy between “showcase and reality.” Projects that appear innovative and modern on paper in fact function as decorative elements of the existing economic model. No new production facilities are being created, the export portfolio is not changing, and the share of the non-oil sector in employment is not increasing (World Bank, 2024b). Since diversification does not go beyond rhetoric, its outcome is effectively zero.

The reported growth that does occur is driven purely by the tightening of tax policy. The government is not shaping the economy; it is merely taxing existing value more aggressively (World Bank, 2024). This mechanism delays the crisis but does not resolve it. This has become one of the most important trends in Azerbaijan’s economy in recent years. The increase in non-oil revenues is presented in official figures as evidence of economic diversification, but in reality, the source of this growth is intensified fiscal pressure on small and medium-sized enterprises, an increase in fines, and the artificial expansion of the tax base.

What makes this particularly dangerous is that the economy itself is not expanding; the state is simply strengthening tax collection. As a result, economic dynamism is stifled. Two facts illustrate this most clearly: according to independent assessments, between 2019 and 2025 Azerbaijan’s economy grew by only 16 percent in real terms, while budget revenues increased by nearly 65 percent. The pace of economic growth is being crushed under the weight of the much faster expansion of the budget. Through this mechanism, the government merely postpones problems to future years. At the same time, shrinking financial space will eventually exhaust the limits of this approach as well. In a collapsing economy, “growth through collection” will sooner or later become impossible.

Infrastructure Spending or Mega-Corruption

Azerbaijan’s infrastructure policy appears to be designed to finance a future crisis. Roads, bridges, stadiums, and parks require massive financial resources, yet they generate no meaningful returns—neither in terms of economic activity nor the creation of new productive entities. For infrastructure to generate value, it must be accompanied by a business ecosystem, local production, innovative sectors, and a competitive environment (Réka Juhász, Nathan J. Lane, Dani Rodrik, 2023). In the absence of these components, numerous projects merely create cash circulation from one construction site to another and provide temporary employment.

At the same time, infrastructure investments are guided not by economic needs but by political priorities. Such projects serve as financial channels for companies close to the ruling family and the state, ultimately turning into mechanisms for rent distribution (OCCRP, 2017).

As a result, investments worth billions do not function as “value-creating” projects but as “value-consuming” ones. This not only increases the burden on the budget but also causes a loss of wealth in the economy: money is spent, yet the economic system does not move. Everything is consumed by the feeding of mega-corruption.

Why This Model Only Holds Until 2030

As rents decline, the limits of statistical manipulation are also reached. Falling budget revenues combined with a growing social burden force the government toward increasingly harsh tax policies, rendering the status-quo preservation model unworkable (Ross, M. L., 2012).

At this stage, the long-used technique of “governing through numbers” loses its effectiveness, because manipulation functions only in times of resource abundance. As rents shrink, cosmetically polishing budget indicators becomes both more difficult and more expensive: the gap between rising expenditures and declining revenues grows too large to be concealed by statistical illusions. As social expectations rise, the state attempts to compensate for its limited financial capacity through stricter taxation, which in turn weakens economic activity and expands the base of discontent (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012).

The collapse of budgetary makeup thus exposes the political model in its essence. The existing system, having lost the buffer created by rent, lacks any alternative mechanism to preserve its stability. A model that maintains the status quo solely through money turns against itself once financial resources diminish, and for the first time the political architecture confronts reality on reality’s own terms.

The End of the “Stay Quiet, Take Your Welfare” Era

People can no longer swallow the government’s fabricated numbers; they measure welfare in the marketplace. This is one of the most visible yet unacknowledged aspects of Azerbaijan’s socio-economic reality. Society sees far more clearly the reality hidden behind nominal indicators: with the same salary, people can buy less each month, and household budgets are exhausted more quickly.

Because domestic production is weak, most of the market is supplied through imports, and global price fluctuations are transferred directly onto the population. Moreover, higher customs duties further accelerate retail price increases. Faced with this trend, the government responds merely by lying.

People also no longer trust the state’s nominal social support system, because services have lost their function in terms of both quality and accessibility. As a result, private expenses borne by households rise sharply: private clinics, tutors, supplementary education courses, transportation, and utilities consume a large share of family budgets.

By manipulating employment statistics, the government conceals the unemployment problem; official data classify experimental, unstable jobs as employment. In reality, unemployment—especially among young people—destroys hopes related to economic, psychological, and social prospects. One consequence of this is the mass emigration of young people: the search for better income, a fairer environment, and a more predictable future is driving the younger generation out of the country. Moreover, one out of every two workers is employed in the informal sector without pension or health insurance. This means that in the near future hundreds of thousands of people will reach old age without pension rights, dependent on minimal social allowances.

Thus, the sharp contrast between the prosperity depicted in statistics and lived reality generates both social fatigue and a crisis of trust within society. Numbers have lost their power to conceal real conditions. As the political model suppresses any form of change, the rent-based status quo collapses.

In this situation, the government will cut spending, increase borrowing, and face deepening social discontent. Each of these options carries political consequences: reduced public spending further impoverishes the population, borrowing undermines economic sovereignty, and rising discontent calls the regime’s legitimacy into question. In other words, all pillars of the social contract are collapsing. The model that promised people “minimal welfare in exchange for silence” no longer works. This signals the collapse of the main pillar of the authoritarian system—an impending legitimacy crisis (Seymour Martin Lipset, 1959).

Either Money or Fear

For authoritarian regimes heading into the post-oil era, two mutually exclusive paths remain. The first path is that of genuine reform. This would require the political power to relinquish its monopoly, to abolish all privileges that grant economic groups fully subordinated to the political system access to state resources, and, more broadly, to ensure that those represented in political power withdraw either from business or from politics altogether. Legal mechanisms addressing conflicts of interest would have to function fully. The judiciary would need to become independent, real parliamentary oversight would have to be established, and genuine electoral competition ensured. This would mean the voluntary sharing of the dominance that the regime has built over decades and the dismantling of its power architecture. Aliyev has neither the political will nor the institutional foundations to take such a self-weakening step. Therefore, the system instinctively chooses the second path: a transition toward harsher authoritarianism in a post-opposition era. In other words, it seeks to compensate for declining resources through the intensified use of coercive power. To achieve this, repression is further escalated (Henry Hale, 2014).

Thus, the tightening we are currently observing is neither accidental nor spontaneous. It is the activation of the coercive apparatus to preserve eroding economic foundations. The first element of this process is the expansion of threat rhetoric: the system redirects public attention toward “internal and external enemies” in order to obscure economic difficulties and attempts to govern political reality through a constant sense of danger. In parallel, the activity of the police–prosecutorial apparatus and the State Security Service (DTX) intensifies. Law enforcement bodies increasingly function as political actors regulating social behavior. Moreover, the troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs—the Internal Troops—are placed directly under presidential control; their mandate, previously focused primarily on guard and protection duties, is expanded toward law-enforcement functions, including the authority to detain individuals (Meydan TV, December 2025).

Another crucial component of harsher authoritarianism is the invention of enemies. In order to divert public dissatisfaction away from economic and governance failures, the regime portrays NGOs, political émigrés, the media, and even mutually contradictory Western and Russian influences as internal threats. Alongside this narrative, “red lines” are broadened: every criticism, every behavior, every word is deemed dangerous and prohibited (Elman Fattah, Nov 2025).

As a result, the space for citizens’ free political behavior is reduced to zero, and people find themselves colliding with “invisible barriers” in everyday life—only to end up in prisons.

Yet no matter how systematic this hardening becomes, it does not solve the underlying problem. Repression is capable only of postponing the crisis, because the source of the crisis is neither instability nor security risks. The source of the crisis is the exhaustion of governance itself. Banning everything does not halt decline; it merely alters its trajectory: it suppresses social discontent while further aggravating structural weaknesses, pushing the system toward a critical point more quickly and under far less favorable conditions.

Systemic Exhaustion

In authoritarian regimes, information flows are inherently distorted: only “good news” travels upward, while bad news is softened or filtered out through various mechanisms. This distances leadership from reality and leads to decisions being made on the basis of false perceptions. In the absence of alternative expertise or independent diagnostic institutions, the system loses the ability to evaluate itself. As a result, the early signals of crisis continue to deepen without triggering any corrective action (Jared Diamond, 2005).

During the years of the oil boom, the influx of dollars functioned as a soft cushion that concealed incompetence in governance. Mistaken decisions could be corrected with money, inefficient projects compensated through additional financing, and gaps within the state apparatus covered by social packages. In the post-oil era, however, this option no longer exists—there is no money left to correct mistakes.

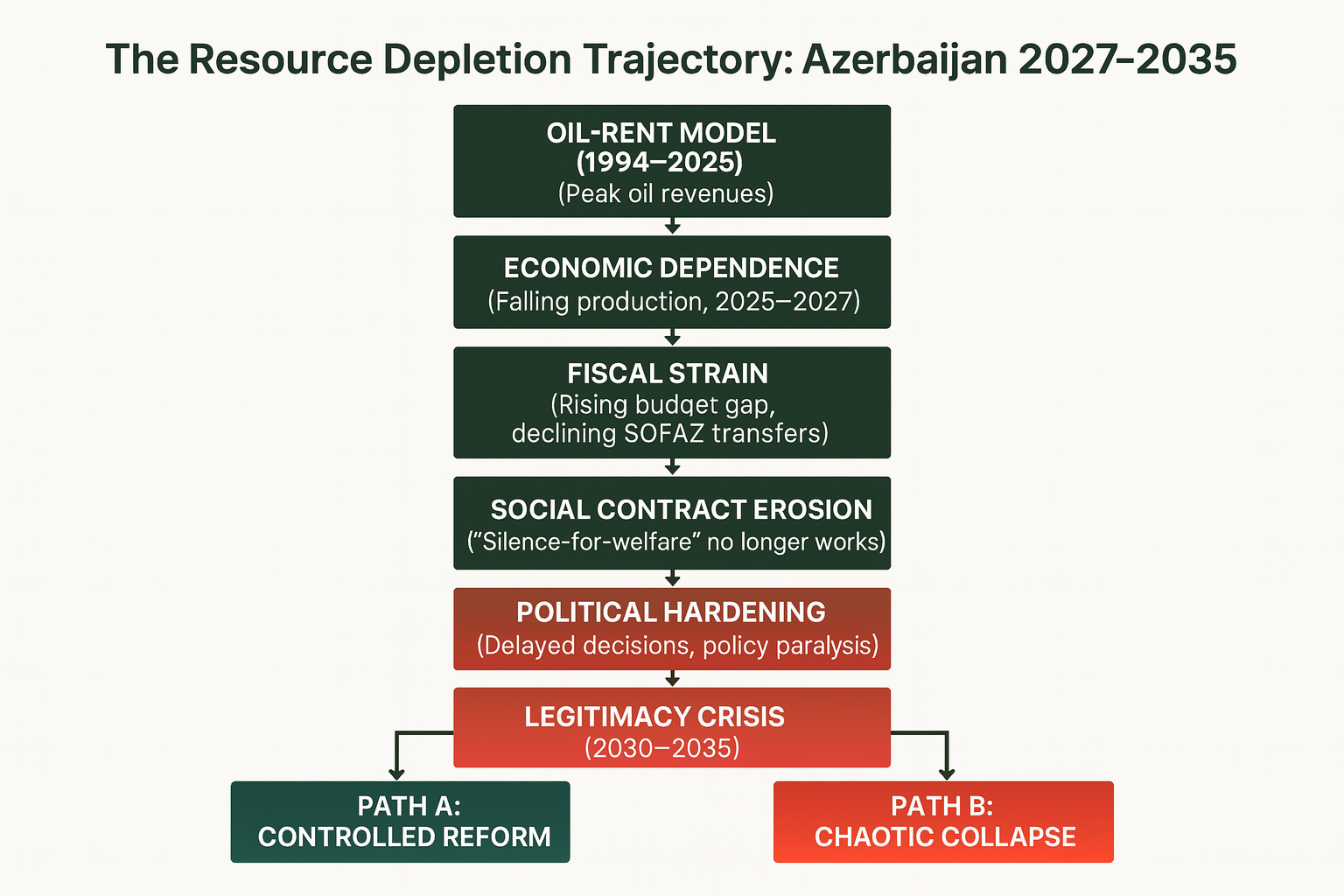

The diagram presented above visualizes, in stages, the approaching crisis of Azerbaijan’s energy-revenue-based governance model. The chart projects that an economic system dependent on the “oil needle” will gradually slide into political hardening and a legitimacy crisis as a result of resource depletion, mounting financial pressures, and the erosion of the social contract. The diagram illustrates the historical direction toward which Azerbaijan’s authoritarian governance model may evolve in the post-oil era. There are only two possible choices: either a gradual transition through controlled reforms (Path A), or an unmanaged and chaotic collapse scenario (Path B).

Crisis Mechanics Toward 2030

As 2030 approaches, the mechanics of the crisis will become increasingly visible. Delayed decision-making not only amplifies the impact of the crisis but also gives it a structural character. Such delays turn any crisis into a larger chain of interlinked tensions. Confusion within the state apparatus will grow, responsible officials will avoid taking risks, and the system will turn into a blocked mechanism. Instead of managing the crisis, the government will once again prioritize decisions aimed at psychologically “distancing” it. This, however, will allow the crisis to penetrate even deeper.

This process will rapidly erode the fabric of trust within society—and even within the bureaucracy itself. As citizens increasingly sense that the governance system has lost contact with reality, the political phase of the crisis—a legitimacy deficit—will be triggered. The bureaucracy, observing that decisions no longer produce tangible results, will completely lose its already minimal capacity for initiative and shift into a passive-reactive mode of behavior. Such erosion of institutional functionality makes the crisis both inevitable and more destructive, because alongside the depletion of resources, the structures capable of managing them are also being exhausted. Under these conditions, even the smallest shock may push the system to the brink of collapse.

From Frozen Stability to Deepening Decline

As the budgetary burden increases, the country falls fully into a fiscal trap. Moreover, a state apparatus formed on the principle of loyalty lacks the strategic thinking, flexibility, and analytical capacity required for crisis management (Venance Riblier, 2023). As a result, governance mechanisms become paralyzed during moments of crisis. Consequently, the effectiveness of the administrative apparatus erodes more severely with each passing year.

In the post-oil era, as the economic system loses its rent-based buffer, fluctuations that were once manageable acquire serious destructive potential. Although the stability of the manat is currently being preserved through foreign exchange reserves, factors such as global volatility in energy prices, rising political risks in the region, and liquidity problems in international markets may turn into severe shocks (BIS, 2023). If the system continues to rely on depleted rent as its primary defense mechanism, then even a minor disturbance will be capable of undermining macroeconomic stability: pressure on the manat will increase, imports will become more expensive, inflation will deepen, and social tension will rise in a cascading manner.

The Gap Between Expectations and Capabilities

Because society has lived for many years under conditions of relative prosperity and broad social packages provided by the state, public expectations significantly exceed real economic capacities. In the post-oil era, the gap between these expectations and the state’s actual capabilities will widen further: rising costs in areas such as food, energy, basic living needs, education, and healthcare will fuel growing public dissatisfaction. The government, in turn, will attempt to contain this dissatisfaction by reverting to old rhetoric—discourses of threat and stability—but these will prove ineffective in the face of economic reality.

As a result, a condition described in social psychology as the “waiting phenomenon” will give way to a “search for an exit,” at which point bureaucratic subordination begins to erode and social passivity gives way to political confrontation (Liene Ozolina, 2016).

Since the existing model fails to meet the demands of the post-oil era, structural reforms have become an unavoidable necessity. However, because political will refuses to accept even the smallest reforms, the system will turn into a mechanism of self-driven decline: capital will leave the country, entrepreneurship will weaken, investments will cease, and the economy will gradually become a collapsing model. In other words, reforms are not merely a tool for economic development—they are the only chance for the system’s survival at all, even in a partially transformed form. The absence of such changes will only accelerate the pace of decline.

Two Possible Paths

The first path envisages consistent and gradual transformation from within the system: decentralization of power, transparent budgetary mechanisms, partial restoration of political pluralism, and the gradual implementation of economic liberalization. Although painful, this path allows for a controlled transition and protects the country from chaotic upheaval. However, such a transformation is possible only with political will, elite consensus, and the establishment of a new social contract with society. Unfortunately, under the current political configuration, such will does not exist.

Under the second path, transformation will be carried out by time itself—more harshly and far more destructively. The scenario of chaotic collapse will be accompanied by deepening economic decline, intensifying social unrest, fragmentation within the state apparatus, and loss of control. In this scenario, the regime will chase the crisis, while the crisis will systematically destroy the system’s weakest points. In the post-opposition era, where alternative political centers have already been eliminated, neither the authorities nor society will be capable of leading such a transition. The process will unfold spontaneously and uncontrollably.

Conclusion

The fundamental problem of Azerbaijani authoritarianism lies in the rhythm of history. Historical processes are stronger than the artificial stability generated by oil revenues, because a political system built on an exhaustible resource cannot possess long-term sustainability. The oil era was able to slow the rhythm of history but not alter it; the post-oil era will accelerate this rhythm and force the system to confront its own reality. Time lies ahead, and no one has ever succeeded in signing an agreement with it. This is the harshest and most inevitable test the regime will face.

At the current stage, the system’s greatest weakness lies precisely in its inability—or unwillingness—to perceive this rhythm. For years, Azerbaijani authoritarianism has learned to conceal crises through communication and to postpone structural problems demanding change through administrative means. Yet the rhythm of time cannot be halted by administrative tools: as economic depletion deepens, the social contract begins to collapse. The dictates of historical processes present Azerbaijan with an unavoidable choice: either the system renews itself and keeps pace with historical rhythms, or those rhythms push it aside. Confronting this reality constitutes the most serious test of Azerbaijan’s political life over the past thirty years, and attempting to overcome it using old methods is as impossible as passing a camel through the eye of a needle.

References

BRİ, Nov 2025. “Crude Oil Production Declines Rapidly In Azerbaijan” https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/xam-neft-hasilat-suretle-azalir/

BP, 2022. Statistical Review of World Energy.https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2022-full-report.pdf

IEA, 2022. Azerbaijan energy profile. https://www.iea.org/reports/azerbaijan-energy-profile/overview

World Bank,2024. Azerbaijan Economic Update. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099734004042433748/pdf/IDU1f54cd5dd17f4514b501b0c11b241db869483.pdf

Minenergy, 2024. Oil and gas figures were announced for 2024. https://minenergy.gov.az/en/xeberler-arxivi/00448

president. az, 2024. AZERBAIJAN Energy projects. https://president.az/en/pages/view/azerbaijan/contract

European Commission, 2021. European Climate Law. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/european-climate-law_en

SOFAZ, 2025a. Information as of September 30, 2025. https://oilfund.az/en/report-and-statistics/recent-figures

SOFAZ, 2024. Dövlət Neft Fondunun 2024-cü il büdcəsinin icrası təsdiq edildi. https://oilfund.az/report-and-statistics/budget-information/52

SOFAZ, Mission and Objectives. https://oilfund.az/en/fund/about/mission

SOFAZ, Information as of September 30, 2025b. https://oilfund.az/en/report-and-statistics/recent-figures

World Bank, 2024b.Azerbaijan. https://www.worldbank.org/ext/en/country/azerbaijan

World Bank, 2024. Macro Poverty Outlook for Azerbaijan. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099734004042433748

Réka Juhász, Nathan J. Lane, Dani Rodrik, 2023. THE NEW ECONOMICS OF INDUSTRIAL POLICY. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31538/w31538.pdf

OCCRP, 2017. Azerbaijan Laundromat & Infrastructure Projects. https://www.occrp.org/en/project/the-azerbaijani-laundromat

Ross, M. L. 2012. Why We Feel Unsafe When We Get Rich? Review on the Empirics of Corruption, Oil Rents and Insecurity in Nigeria. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=100244

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J, 2012. Why Nations Fail. p-34,37. https://ia801506.us.archive.org/27/items/WhyNationsFailTheOriginsODaronAcemoglu/Why-Nations-Fail_-The-Origins-o-Daron-Acemoglu.pdf

Seymour Martin Lipset, 1959. Political. p-31,65 Man.https://dn720501.ca.archive.org/0/items/politicalmansoci00inlips/politicalmansoci00inlips.pdf

Henry Hale, 2014. Patronal Politics. P-33,38 https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/patronal-politics/4C1B4D49A7F17739E75A5AB7B66E2115

Meydan TV, December 2025. Daxili qoşunlara “saxlama” səlahiyyəti verilir: hərbi qurum mülki səlahiyyətlər qazanır. https://www.meydan.tv/az/article/daxili-qosunlara-saxlama-s%c9%99lahiyy%c9%99ti-verilir-h%c9%99rbi-qurum-mulki-s%c9%99lahiyy%c9%99tl%c9%99r-qazanir/

Elman Fattah, Nov 2025. The End of Politics in Azerbaijan: The Beginning of a Post-Opposition Era. https://kharcenter.com/en/expert-commentaries/the-end-of-politics-in-azerbaijan-the-beginning-of-a-post-opposition-era

Jared Diamond, 2005. Collapse. P-419,420 https://travolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Collapse__How_Societies_Choose_to_Fail_or_Succeed-Jared-Diamond.pdf

Venance Riblier, 2023. The Fiscal Cost of Public Debt and Government Spending Shocks. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2309.07371

BIS, 2023. Annual Economic Report. https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2023e.htm

Liene Ozolina, 2016. A state of limbo: the politics of waiting in neo-liberal Latvia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305748001_A_state_of_limbo_the_politics_of_waiting_in_neo-liberal_Latvia