For easier reading and comprehension, this research by the KHAR Center will be presented in multiple parts.

For the second part of the research paper

For the third part of the research paper

Summary

This study prepared by the KHAR Center explains the political processes that occurred in the Republic of Azerbaijan after the collapse of the USSR and how the country’s democratic prospects were replaced by an authoritarian regime. The research also analyzes, step by step, the authoritarianization process observed in Azerbaijan since 1993. It focuses on how the authoritarianism that began with Heydar Aliyev’s return to power transformed into familial authoritarianism during Ilham Aliyev’s rule, and how at different times it was characterized by advisory, soft, and hard authoritarian models. The study emphasizes the transformation of state governance into corruption networks, the regime’s shifting and inconsistent ideological positions, and the persistence of political repression.

The second part of the study will provide an in-depth analysis of the modifications of authoritarianism in the post-Karabakh period.

The third part will explore Ilham Aliyev’s role in international authoritarian coalitions and regional authoritarian integration initiatives, focusing on the West’s tolerant attitude towards him. It concludes that the West’s compromises on human rights and democratic principles have contributed to the consolidation and international legitimacy of the authoritarian regime.

Introduction

Post-Soviet countries have experienced the transition period after the USSR’s collapse in three different directions. The first direction consists of the Baltic states, which experienced successful democratization. The second direction includes countries such as Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, which oscillated between democratization and authoritarianism. The third direction comprises countries where democratization processes have stalled and authoritarianism has deepened without significant resistance—though some weak internal resistance persists—such as Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia. The fourth direction includes countries where signs of democratization have never been visible, such as Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan (Elman Fattah 2019).

In a few former Soviet states, including Georgia in 2012 and Armenia in 2015, a transition from a presidential system to a parliamentary republic took place following “constitutional reform” referendums. The tendency toward parliamentarism in post-Soviet countries can be considered an initial step toward democratization. For example, in Georgia, despite rising authoritarian tendencies in recent years, the continued presence of electoral democracy attributes remains notable. Kyrgyzstan can be described as Central Asia’s only soft authoritarian state, and Armenia has stepped onto the path of democratization with the rise of Nikol Pashinyan to power.

In contrast, Azerbaijan under the Aliyevs has followed not a path toward parliamentarism, but toward "sultanistic despotism," through enhanced presidential powers, representing the South Caucasus’s archetype of hard authoritarianism.

The aim of this KHAR Center study is to analyze the authoritarianization process in Azerbaijan since 1993 in stages and to examine this process through the lens of internal (institutional changes, ideological orientations, political repression) and external (Western state attitudes) factors.

The central thesis of the study is that since 1993, Azerbaijan’s political system has gradually evolved in an authoritarian direction—transforming from a strong presidential institution to a stabilized familial authoritarianism, and eventually sliding into monarchical authoritarianism characterized by autocratic repression and a highly centralized executive power.

Main research question:

What internal and external factors have influenced the deepening of Azerbaijan’s authoritarian political structure, and what could be the future trajectory of this system?

Methodology

This study is based on a synthesis of descriptive and analytical approaches.

The following methods have been used in the research:

- Historical-institutional analysis: The main changes in Azerbaijan’s political system, including the transfer of power within the family and constitutional reforms, are analyzed in historical sequence and institutional framework.

- Analysis of political repression indicators: Repressive policies targeting independent media, NGOs, and opposition politicians have been evaluated based on international reports (Freedom House, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, etc.) and local observation data.

- Geopolitical analysis of Western-Azerbaijan relations: The policies of Western actors such as the United States and the European Union in the areas of energy security, regional stability, and human rights are reviewed, and their support for the Aliyev regime is analyzed.

Academic literature, international reports, leaked documents (e.g., Panama Papers, Pandora Papers), media publications, and political speeches were used as sources.

This methodological approach aims to ensure that the study has both empirical grounding and theoretical depth.

The Authoritarianization Process in Azerbaijan

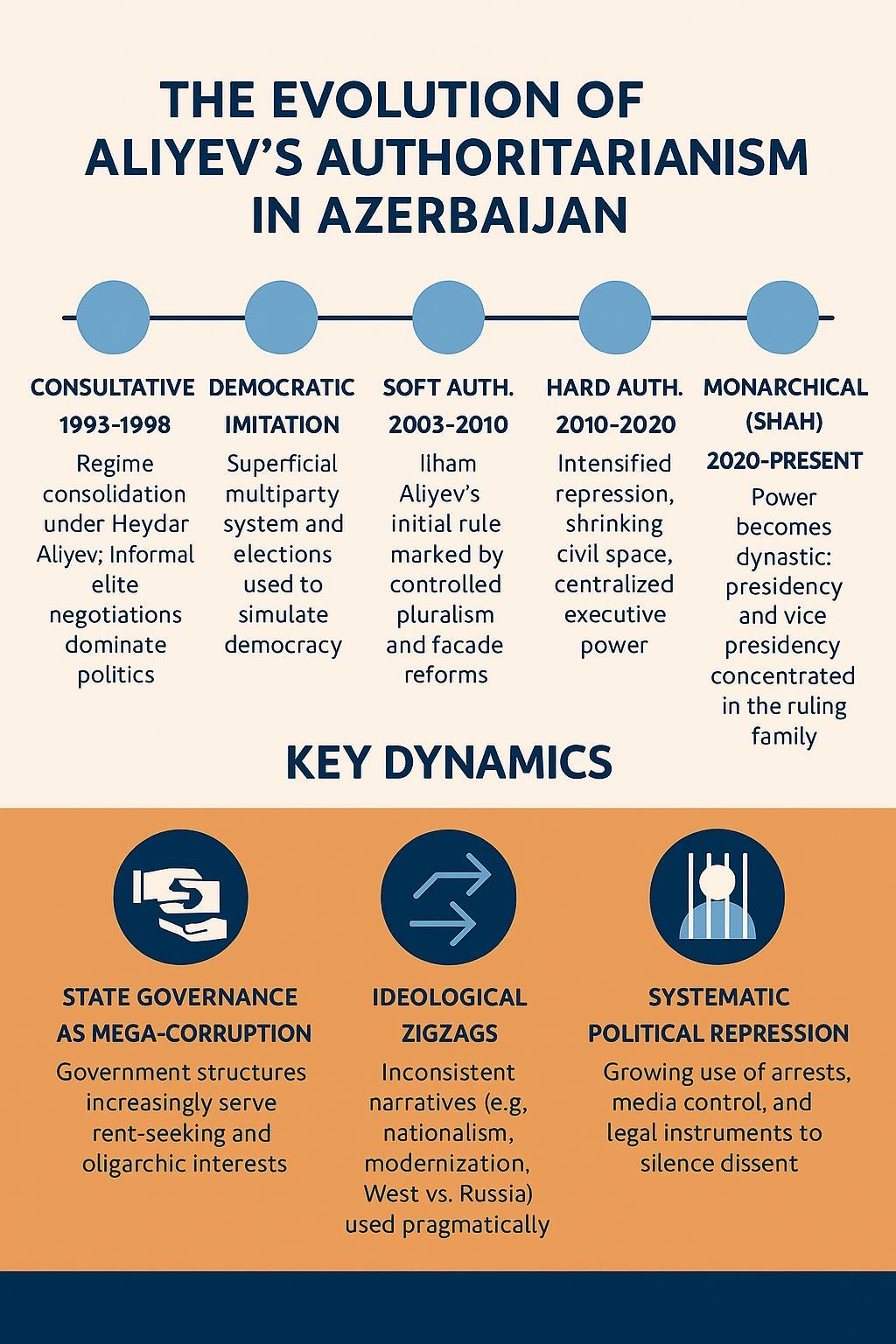

Following the interruption of democratization processes in 1993, the rise of the Aliyev-led authoritarianism in Azerbaijan can be divided into several stages (Infographic 1):

- Consultative Authoritarianism (1993–1998): This stage, marked by Heydar Aliyev’s return to power, maintained formal institutions but restricted real political competition.

- Imitation of Democracy (1999–2002): During this stage, some reforms were introduced as part of cooperation with Western countries, but the actual aim was the consolidation of power.

- Soft Authoritarianism (2003–2010): Following Ilham Aliyev’s election as president, a softer form of authoritarianism was implemented, coupled with economic stability and modernization.

- Hard Authoritarianism (2011–2020): Repression intensified with targeted attacks on independent media, NGOs, and political activists, leading to a highly repressive regime.

- Monarchical “Shah” Authoritarianism (2021–present): This stage is characterized by centralized, family-based rule and the effective transition to a hereditary power system (Elman Fattah 2019).

Infographic 1

Infographic 1

In particular, the transfer of power to Ilham Aliyev following Heydar Aliyev’s death in 2003, and the sharing of the presidency with his wife Mehriban Aliyeva (appointed as Vice President in 2017), signaled the gradual transformation of authoritarian rule into a dynastic model. This type of governance is known in political science as familial authoritarianism (Levitsky and Way 45).

The dynamic modifications of the Aliyev authoritarianism are most clearly manifested in three key issues:

1. The mega-corruption nature of state governance

At this stage, state structures ceased to be merely administrative bodies and turned into parts of a corruption network. Alongside the non-transparent distribution of oil revenues and the enrichment of oligarchic groups linked to the family and close circle, the subordination of the state budget to the “family circulation” is observed.

International documents such as the Panama Papers and Pandora Papers played an important role in exposing these processes. The Panama Papers speak about how the ruling family governing Azerbaijan built a secret empire of wealth, while the Pandora Papers mention the purchase of dozens of properties in London worth approximately 700 million dollars by Azerbaijan’s ruling Aliyev family and their partners.

2. Inconsistent ideological zigzags

The ideology of the Aliyev regime is not built upon a stable line; on the contrary, it has changed depending on time and circumstances. For example:

- Cultivation of “Heydarism” alongside Soviet nostalgia,

- Anti-Western rhetoric alongside calls for integration with the West,

- Unstable ideological floundering between Turkism, pan-Islamism, and modern secularism.

This shows that the zigzags do not stem from the ideological essence of the regime but serve functional and tactical purposes.

3. Continuous political repression

Since 1993, political repression has continued with a consistently increasing trend:

- Arrest of opposition leaders in the late 1990s;

- Mass repressions after the 2003 and 2005 elections;

- From 2013 onward, the suffocation of independent media and NGOs;

- After 2020, the trend of complete elimination of independent media.

These repressions are carried out both on the physical level (arrest, pressure) and on the informational level (disinformation, troll armies).

That is, Azerbaijan’s authoritarianization process manifests itself in the total violations accompanying all elections, the manipulation of results in favor of the political power, the subordination in practice of the branches of power—the executive, judiciary, and legislature—which are constitutionally independent, to the president; the complete destruction of press freedom; the complete control of the country’s entire information space, TV channels, newspapers, and even online media; the annihilation of all attributes of a multi-party political system; the exposure of opposition political activity to severe and continuous political repression; the transformation of civil society into GONGOs; and the labeling of those who resist as the “fifth column” and declaring them foreign agents or traitors.

All of this constitutes the governance formed under the membership of Azerbaijan in the OSCE and the Council of Europe, and its cooperation with the European Union.

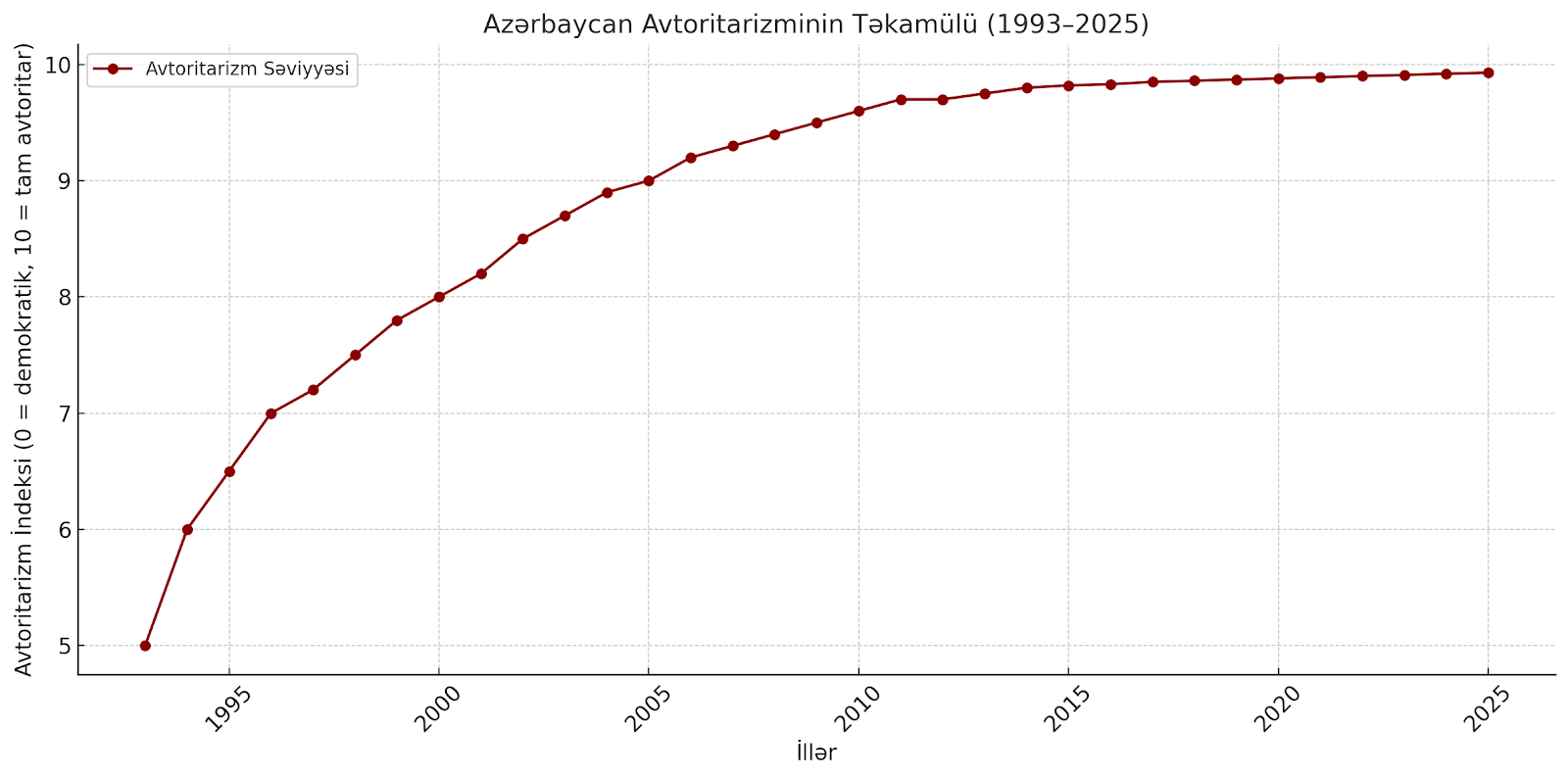

Graph 1

Graph 1

This diagram reflects the evolution of authoritarianism in Azerbaijan between 1993 and 2025. With Heydar Aliyev’s return to power in 1993, authoritarian tendencies in the country began to strengthen. From 2003 onward, during Ilham Aliyev’s presidency, this trend deepened further. In particular, the constitutional amendments of 2009 and 2016, the suppression of independent media and civil society, the holding of non-competitive elections, and the increase in political repression led to the dismantling of political pluralism in the country. By 2025, authoritarianism had taken on a systematic and institutionalized character. (Freedom House, 2023)

In the early years of independence, prior to Heydar Aliyev, the primary concern of the society—especially among the intellectual segment—was not the transition to democracy. During Elchibey’s rule, reforms in this area had a consistent character. Freedom of the press during this time was at a remarkably high level compared to the rest of the 34 years of independence. (Altstadt, Audrey L. 1992). The central issues of the period were the ongoing war with Armenia and the unresolved political crisis against the backdrop of weak central governance.

After the military uprising in Ganja, Heydar Aliyev came to power in June 1993, and the process of “re-prioritization” began to accelerate. Democracy, legal reforms, press freedom, and political freedoms were severely restricted. In return, central authority was strengthened and “stability” in governance was achieved. (U.S. Department of State, 1993)

The ceasefire achieved in May 1994 in the war with Armenia created favorable conditions for attracting investment from transnational oil companies. Thanks to the agreement signed in September 1994—known as the “Contract of the Century,” concerning the extraction and export of Baku oil to world markets—Heydar Aliyev gained substantial support from the West through alignment with transnational corporate interests.

It is an evident fact that since 1995, the Aliyev regime has enjoyed significant international political support. Heydar Aliyev built his authoritarian rule on the slogans of “balanced foreign policy” and “stability,” aligning with the characteristics of “consultative authoritarianism.” The public parts of all his meetings with European guests would typically begin with the phrase “political stability” and focus on Azerbaijan’s desire to integrate into Europe and its commitment to exporting energy resources to the West. Meetings with Russian and Iranian officials would proceed under the theme of recalling past personal friendships—Soviet KGB and Politburo memories with Russians, and the “brotherly” relationships formed in Nakhchivan during 1991–1992 with Iranians. Meetings with Turkish officials would echo the slogan “Two states, one nation,” centered around the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan project. (Elman Fattah, 2019)

This not-so-sophisticated “diplomacy” was presented by the regime as “balanced foreign policy.” In this context, the reform proposals presented by European institutions were essentially framed as managed transformations. OSCE’s election reforms, media freedom, and human rights demands, along with the reform packages tied to membership in the Council of Europe, were adapted to suit the authoritarian reality of the country.

Azerbaijan was accepted into the Council of Europe in November 2000 with the stain of parliamentary elections held with total violations. According to the final report of the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, the main opposition party Musavat and the ruling New Azerbaijan Party (YAP) received very close vote percentages. However, official results credited YAP with 63% and Musavat with only 4%. The relatively successful result for Musavat in this election forced the government to change the proportional election law—its primary problem with retaining power—through a disputed referendum one year after joining the Council of Europe. This effectively limited the development of the multiparty political system, one of the essential pillars of democratic development.

By the late 1990s, statements like “We have ensured stability,” “Democracy is not a commodity you can buy at the market,” and “We have democracy, and we are developing it” were common responses to criticism of the lack of democracy. After the transfer of power from father to son in the 2000s, these were replaced with the narrative that “Economic prosperity is the main condition for democratic development” (Heydar Aliyev and Rule of Law, 2008). This narrative laid the foundation for the “soft authoritarianism” that would be implemented in the early years of Ilham Aliyev’s rule.

If we continue to track Azerbaijan’s authoritarian timeline in the context of foreign policy, the “balanced foreign policy” myth, popular during Heydar Aliyev’s time, had so deeply intoxicated the regime that Ilham Aliyev’s administration began with the propaganda of “faithfully continuing a successful political course.” In reality, there was no reason for concern. Ignoring toothless protocol statements and “routine declarations,” the regime’s foreign political support was even stronger and more overt than before. Prior to the 2003 presidential election, the father-son “alternative” candidacy, the appointment of Ilham Aliyev as prime minister (the second most powerful official) by a decree allegedly signed by President Heydar Aliyev—whose health status was unknown for months—while in fact he was receiving treatment in Turkey, and then his immediate departure on leave the very next day, the falsification of election results in favor of Ilham Aliyev, and the disgraceful transfer of power from father to son were not only praised but directly facilitated by Western political centers. (Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, 2003, p. 13)

Despite Azerbaijan’s authoritarian governance model, the political and economic relations of Western states with Baku have been based primarily on pragmatic interests. In particular, access to energy resources and regional security have played dominant roles in the West’s policy toward the Azerbaijani government. As a result, fundamental issues such as human rights violations and the weakening of democratic institutions have either been ignored or addressed only through symbolic criticism. (Knaus and Cox, 2015)

Actors like the United States and the European Union have highlighted Azerbaijan’s strategic position—especially the Caspian Basin’s energy reserves—as an alternative energy source and continued cooperation with the Aliyev regime in this context. For example, the “Southern Gas Corridor” project occupies an important place in the EU’s energy security policy, and its successful implementation has granted the Azerbaijani government international legitimacy. (Cornell, 2011)

In this context, the West’s indirect support for Aliyev’s authoritarianism can be analyzed under the concept of “tolerance of authoritarianism for stability.” For the sake of regional stability and energy security, the West has sidelined its commitment to democratic values. This approach has been openly evident in the political support given to the Aliyev regime, despite electoral fraud and political repression in 2003 and 2013. (Freedom House, 2024; Human Rights Watch, 2015)

The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S. brought global attention to security issues, significantly weakening support for democracy promotion. The horror induced by the attack was not limited to the immediate disaster; the fear it created disrupted not just a single country or region but the traditional global security order. The root of today’s global crises can be traced back to that event. Hopes for the so-called “new world order” were destroyed by the 9/11 attacks. That incident triggered the collapse of the existing system, without building a new one.

In 2003, the possibility of democratic change in Azerbaijan was effectively nullified by international realignments shaped in the post-9/11 context, prioritizing energy and security. The deal struck with the Aliyev family—exemplified by Heydar Aliyev being transported from treatment in Turkey to the Cleveland Clinic in the U.S. via a Russian aircraft—derailed any democratic transformation. From that moment on, Azerbaijan veered away from becoming part of Europe or at least the “soft authoritarian” model of the South Caucasus, and moved toward the despotic path of Gulf monarchies enriched by energy wealth.

Thus, hope for democratic change was extinguished, and this disillusionment triggered a new wave of migration. The first political migration wave from contemporary Azerbaijan to Europe began. This migration expanded after the 2005 parliamentary elections and continues to grow to this day.

To summarize, three key political developments in Azerbaijan’s post-Soviet history—the 2002 referendum eliminating the proportional electoral system, the events of 2003, and the 2009 constitutional amendment abolishing the two-term presidential limit—collectively shifted the country’s trajectory from semi-democracy to institutionalized authoritarianism. This transformation was finalized in the last five years through the dismantling of civil society and the functions of political parties.

As noted above, Azerbaijan’s chance for democratic change was lost in 2003 due to a deal made with the Aliyev family by the main political centers capable of exerting real influence on Baku (the U.S., Turkey, Russia). However, part of this deal also included hope that democratic reform in Azerbaijan would proceed more smoothly under Ilham Aliyev. The “foreign political support” extended to the Aliyev regime—mainly due to oil and overall geopolitical interests—could not be limitless. While the regime believed it had convinced the West with its STABILITY narrative, academic and political circles in Europe clearly understood that long-term stability depends on legitimacy derived from democratic processes. This was such a well-known formula that even during periods of full political support, the West would quietly remind the Aliyev regime of this fact. Initially, the regime regarded these reminders as mere protocol phrases in diplomatic meetings, but over time, it began to resent them—especially as support waned and demands began to be voiced more loudly and clearly.

During Ilham Aliyev’s first presidential term (2003–2008), the West’s policy toward Azerbaijan can conditionally be described as “sincere criticism in the name of reform” or “encouraging reform through belief in democracy.” Examples of this include the release of prominent opposition leaders imprisoned during the 2003 repressions in the spring of 2005, the rapid lifting of their criminal records allowing them to run in parliamentary elections, and Ilham Aliyev’s decree banning local authorities from interfering in elections and requiring the inking of voters’ fingers to prevent multiple voting. Everything appeared to be going well at first, and alongside the West, some local politicians began to believe that the train of reform had finally left the station. There was hope that Azerbaijan’s transition to democracy would not occur through “revolution” like in Georgia or Ukraine, but through “evaluation.”

However, in September 2005, two ministers were accused of colluding with the opposition and arrested for allegedly plotting a coup inspired by the so-called “color revolutions” in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan (2003–2005), which were claimed to have been organized by the West. When it became clear that this script had been written in the Kremlin and executed in Baku, it was also realized that the policy of democracy imitation could not survive in the interpretation of the second Aliyev. The “soft authoritarianism” that lasted only a year or two would soon give way to hard authoritarianism.

Ilham Aliyev’s new method of governance would, on the one hand, embody dynastic rule inspired by the monarchism of the Arab region, and on the other hand, as Boris Nemtsov put it, reflect the "bandit authoritarianism" of Putin’s Russia—the locomotive of the “international authoritarian coalition” (RFE/RL 2017). And as a logical consequence of this direction, it was to be expected that Western political support would not remain at the same level.

The Collapse of Hopes for the “Reformer” Aliyev

It can be stated with certainty that after 2013, both local and international analysts should have come to a firm conclusion that Ilham Aliyev would not pursue any real reforms. It is entirely clear that the “consultative” authoritarianism formed during Heydar Aliyev’s time, which was passed on to Ilham Aliyev as a model of “democracy imitation” and “soft authoritarianism,” was not perceived by him as a platform for returning to democracy, but rather as an opportunity to transition into hard authoritarianism—fueled by the propaganda of his supporters in the West. From this perspective, the core question should have been reframed at least 15 years ago—not as “How to reform the authoritarian regime in Azerbaijan?” but “What is the most optimal path for change?”

Now, the country has fully descended into what can only be described as “familial authoritarianism.” Political rights and the space for political activity in Azerbaijan have been severely restricted—one might even say abolished. All mechanisms enabling the operation of political parties have been dismantled. Opposition parties have effectively been reduced to “dissident clubs.” Harassment and persecution of political opponents have intensified. The arrest of innocent people on various fabricated charges has become routine. Fair trials are impossible in the country. The use of severe torture against accused persons in police departments and temporary detention facilities, combined with courts reading out politically motivated decisions in droves, demonstrates that the scale of repression has reached unimaginable levels. Currently, there are more than 350 political prisoners in the country, over 20 of whom are journalists.

The Evolution of Authoritarianism in Azerbaijan in the Context of the Destruction of Independent Media, Civil Society, and Political Parties

Although Azerbaijan made short-term efforts to build democratic institutions after gaining independence, by the mid-1990s the deepening of authoritarianism began to be observed. As a result of this process, the main democratic pillars—independent media, civil society, and political parties—were systematically weakened, brought under control, and, after 2020, driven to the brink of functional extinction.

The Destruction of the Media

The weakening of the media in Azerbaijan was implemented in stages. In the initial stage, during the early 2000s, independent newspapers were subjected to economic pressure and fines. Later, physical violence, arrests, and blackmail tools against journalists were systematically expanded. Their scope of activity was restricted, while state-controlled media outlets were transformed into instruments promoting the state’s position under the guise of "national interests."

In 2017, most independent news websites in the country were blocked (e.g., Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Meydan TV). Finally, with the adoption of the “Law on Media” in 2021, requirements such as licensing of media outlets, registration of journalists, and inclusion in a state registry were introduced. This officially confirmed the transformation of the media into an administrative tool of control.

Main stages and mechanisms of media destruction: Legal and institutional tools

- Criminal defamation laws have been used as the main legal tool for pressure on journalists. Defamation remains criminalized in the Azerbaijani Criminal Code (Articles 147 and 148).

- The “Law on Media” (2021) – This law compelled media entities and journalists to register in a state-created Media Registry. In effect, this functions as censorship and an informal accreditation mechanism.

Physical and psychological pressure: Repressions against journalists

- Elmar Huseynov (editor of Monitor magazine) was assassinated in front of his home in 2005.

- From 2006 to 2023, systematic pressure on independent media, including the arrest, beating, and forced exile of numerous journalists, became widespread.

- In 2023–2024, the arrests targeting Abzas Media, Toplum TV, and Meydan TV clearly demonstrated the Azerbaijani government's shift toward a strategy of total control in the information war. These events

- Criminalized journalism in the country;

- Systematically eliminated sources of critical information;

- Grossly violated international human rights obligations.

Media Freedom Rankings

Reporters Without Borders, 2024: 164th place (out of 180 countries) (RSF 2024)

Freedom House, 2024: 0/4 (Score on Media Freedom) (Freedom House 2024)

CIVICUS Monitor, 2023: “Repressed” category (CIVICUS 2023)

These repressions have dealt a severe blow not only to media freedom but also to the broader right of society to access information.

Thus, the evolution of the authoritarian regime in Azerbaijan has occurred in parallel with the strategic destruction of independent media. The implementation of this process through legal, economic, physical, and technological means has resulted in the local media being reduced to a mere propaganda tool of the ruling power.

The Dismantling of Civil Society

The strength of civil society institutions is a measure of a healthy democratic society. In Azerbaijan, however, repressions against NGOs gained systematic character especially after 2013. The activities of foreign donors were restricted, the registration system for NGOs was tightened, and financial resources were blocked. During 2013–2014, dozens of NGO leaders and human rights defenders were arrested and imprisoned on various charges (tax evasion, illegal entrepreneurship, etc.). In 2024, a new wave of arrests targeting civil society representatives began—and it is still ongoing.

According to Freedom House’s 2024 report, Azerbaijan is classified among the “Not Free” countries and received only 1/12 points for civil society activities (Freedom in the World, 2024).

Although the Azerbaijani Constitution and international conventions guarantee the free operation of civil society, these rights are de facto denied. Since Ilham Aliyev came to power—and particularly since 2013—the repressive strategy against civil society has only intensified.

Legal and administrative pressure

- In 2013 and 2014, amendments to NGO legislation drastically tightened mechanisms related to registration, grant acquisition, and financial reporting.

- Foreign donors can now provide grants only with the permission of the Ministry of Justice.

- NGO registration has become virtually impossible.

Since 2024, nearly all NGOs have been targeted. NGO representatives cooperating with foreign donors have either been imprisoned, summoned for investigation as accused persons, or otherwise subjected to persecution by law enforcement agencies.

Civil Society Ratings

CIVICUS Monitor, 2023: “Repressed” (CIVICUS 2023)

Freedom House (Nations in Transit), 2024: 1/12 (NGO Freedom) (Freedom House 2024)

USAID CSO Sustainability, 2023: 5.7/7.0 (1 – best, 7 – worst) (USAID 2023)

As a result of these pressures, NGOs’ ability to influence society has been entirely nullified. All so-called "civil society" structures currently operating in the country are affiliated with the government. Overall, the destruction of civic initiatives through legal, administrative, financial, and repressive means has paralyzed mechanisms of public oversight and democratic transformation. This has led to increased social passivity, lawlessness, and apathy.

The Elimination of Political Parties from the System

The neutralization of opposition political parties has been one of the main priorities in the evolution of the authoritarian regime. Parties such as the Musavat Party and the Azerbaijani Popular Front Party (APFP) have, at various times, faced the dispersal of their protests, arrests of leaders, and other forms of political restriction.

In 2022, a new “Law on Political Parties” was adopted, tightening the conditions for party registration. Through this law, parties with small membership numbers and weak regional structures were informally removed from the system. At the same time, “loyal” parties supported by the state were granted access to parliament to create an illusion of pluralism.

In the Azerbaijani example, the evolution of authoritarianism is expressed not only in the formalization of the electoral and parliamentary system but also in the wholesale destruction of democratic institutions. The silencing of independent media, the collapse of civil society, and the marginalization of political parties have crippled mechanisms of public accountability and oversight. As a result, the authoritarian system has transformed into a self-reproducing, unquestionable, and alternative-less regime.

References

Altstadt, Audrey L. 1992. The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity under Russian Rule. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Amnesty International. 2018. Report 2017/18. https://www.amnesty.org.

Azərbaycan Dövlət İnformasiya Agentliyi. 2003. “İ. Əliyevin Baş Nazir Təyin Edilməsi Haqqında Fərman.” https://azertag.az/xeber/IHALIYEVIN_AZARBAYCAN_RESPUBLIKASININ_BAS_NAZIRI_TAYIN_EDILMASI_HAQQINDA_AZARBAYCAN_RESPUBLIKASI_PREZIDENTININ_FARMANI-293709.

CIJ (Center for Investigative Journalism). 2021. Pandora Papers Investigation. https://www.icij.org.

Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. 2003. Report on Azerbaijan’s Presidential Election October 15, 2003. https://www.csce.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Azerbaijan-Elections_0.pdf.

Council of Europe, Venice Commission. 2014. Opinion on Media Legislation. Venice: Council of Europe.

Council of Europe, Venice Commission. 2021. Opinion No. 1043/2021 — The Law Restricts Media Pluralism and Independence.

CIVICUS Monitor. 2023. Azerbaijan Country Page. https://monitor.civicus.org/country/azerbaijan/.

Cornell, Svante. 2011. "The South Caucasus: A New Strategic Arena." Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, 213.

Elman Fattah. 2019. Yeni Avtoritarizm və Azərbaycan. Bakı: Qanun.

European Endowment for Democracy. 2017. Civil Society Under Threat in Azerbaijan.

Freedom House. 2023. Nations in Transit 2023: Azerbaijan. Washington, DC: Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org.

Freedom House. 2024. Azerbaijan Country Page. https://freedomhouse.org/country/azerbaijan.

Guliyev, Farid. 2012. “Personal Rule, Neopatrimonialism, and Regime Typologies: Integrating Dahlian and Weberian Approaches to Regime Studies.” Democratization 19 (1): 141–161.

Heydər Əliyev. 2008. Heydər Əliyev və Qanunçuluq. Milli Təhlükəsizlik Nazirliyinin işçiləri ilə görüş, 28 Mart 1998. https://lib.aliyev-heritage.org/az/2635896.html.

Human Rights Watch. 2015. World Report 2015: Azerbaijan. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch. 2022. World Report 2022: Azerbaijan. New York: Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org.

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. 2016. “How Family That Runs Azerbaijan Built an Empire of Hidden Wealth.” https://www.icij.org/investigations/panama-papers/20160404-azerbaijan-hidden-wealth/.

Knaus, Gerald, and Michael Cox. 2015. “The End of Shame: Europe and the Denial of Human Rights.” Journal of Democracy 26 (3): 59–70.

Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OCCRP (Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project). 2021. “Azerbaijan’s Ruling Aliyev Family and Their Associates Acquired Dozens of Prime London Properties Worth Nearly $700 Million.” https://www.occrp.org/en/project/the-pandora-papers/azerbaijans-ruling-aliyev-family-and-their-associates-acquired-dozens-of-prime-london-properties-worth-nearly-700-million.

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). 2001. Republic of Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections, 5 November 2000 and 7 January 2001: Final Report. https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/0/d/14266.pdf.

OSCE/ODIHR. 2015. Republic of Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections, 1 November 2015: Final Report. Warsaw: OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/azerbaijan.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF). 2018. Enemies of the Internet Report.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF). 2024a. 2024 Media Azadlığı Reytinqi. https://rsf.org/en/ranking.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF). 2024b. World Press Freedom Index 2024: Azerbaijan. Paris: RSF.

RFE/RL. 1997. “Bandit Capitalism Versus Capitalism With A Human Face.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/1083971.html.

U.S. Department of State. 1993. Country Report on Human Rights Practices 1993: Azerbaijan. https://www.refworld.org/reference/annualreport/usdos/1994/en/25134.

USAID. 2022. CSO Sustainability Index: Europe and Eurasia 2022 Report. https://www.fhi360.org/wp-content/uploads/drupal/documents/csosi-europe-eurasia-2022-report.pdf.