(This paper was prepared within the framework of post-Soviet authoritarianism research)

Part I

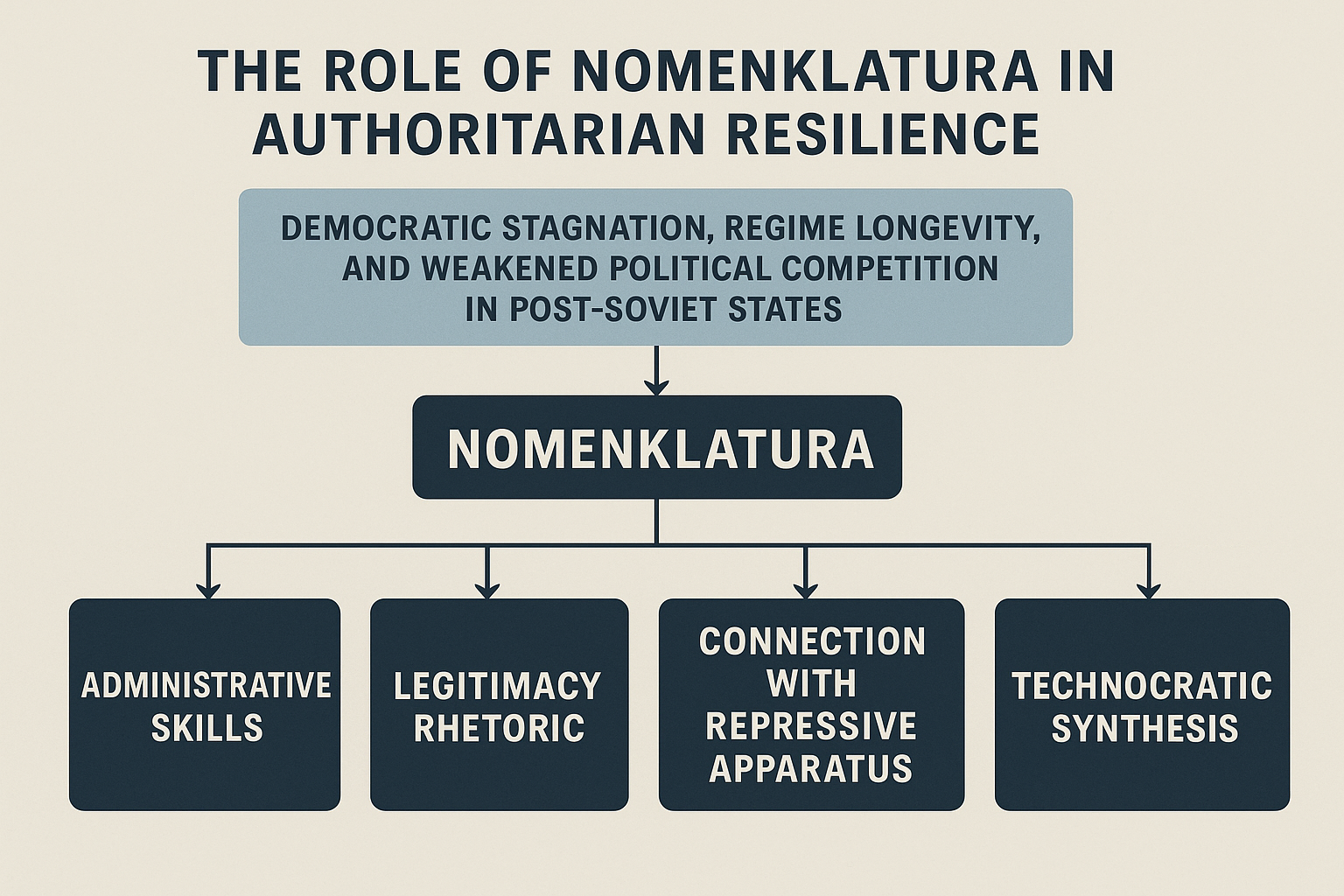

This study demonstrates that the Soviet nomenklatura functions as the structural, ideological, and technocratic backbone of modern authoritarian regimes across the post-Soviet space. The nomenklatura’s administrative capacity, its symbiosis with repressive apparatuses, and its synthesis with digital surveillance technologies position it as a central actor of authoritarian modernization. Its continuity creates structural, cultural, and ideological barriers to democratic transition. Overcoming this influence requires comprehensive transformations in political, institutional, and technological domains.

Introduction

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the post-socialist space entered a new phase of state-building. However, the anticipated democratic transformations either remained incomplete or entirely failed in most countries of the region. While political science has explored various reasons behind this failure, one strategically important yet long-neglected factor is the transmission of the Soviet nomenklatura as a political, institutional, and ideological legacy into the new regimes.

The concept of the nomenklatura refers to the Soviet practice of assigning high-ranking positions to individuals approved by the Communist Party. This system underpinned administrative structures, political loyalty, vertical patronage, and the reproduction of personnel. The cadre elite formed during the Soviet era managed to remain in positions of political and economic power after the USSR's collapse and often played a central role in the formation and sustainability of new authoritarian regimes.

The primary aim of this paper is to analyze the role of the former nomenklatura stratum in the establishment and consolidation of authoritarian regimes in the post-Soviet space in two stages. The central thesis is that the legacy of the nomenklatura constitutes an institutional resource for authoritarianism. This resource is sustained through the preservation of loyalty networks under the guise of political stability and the use of legal-administrative systems for authoritarian objectives.

In this context, the paper first provides a brief overview of the structure and functions of the Soviet nomenklatura and then explains its transformation in the post-Soviet period and how authoritarian regimes have utilized it. Through a comparative lens, the paper will present case studies from Azerbaijan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Georgia to highlight varied outcomes. It ultimately argues that the nomenklatura has become a central element in authoritarian modernization in post-Soviet political systems.

Research Question

How does the continuity of nomenklatura structures hinder democratic transitions in post-Soviet countries?

Core Thesis

The retention of political and economic power by the Soviet nomenklatura elite in post-Soviet countries has obstructed the development of democratic institutions and become a pillar of kleptocratic governance and authoritarian consolidation.

Historical Context: Formation and Function of the Soviet Nomenklatura

The Soviet nomenklatura evolved in parallel with the formation and development of the Soviet Union and permeated all institutional aspects of its existence. The foundations of this structure were systematically laid in the mid-1920s and expanded during Stalin's rule alongside increasing centralization and political control (Hough, 1979a).

The Concept of Nomenklatura

The term “nomenklatura” in the Soviet political system referred to a list of positions whose appointments were controlled by the Party's personnel departments. The Central Committee’s cadre department and local party bodies oversaw these lists, and appointments were made based strictly on “reliability”—that is, personal and ideological loyalty to the Party (Voslensky, 1984a). This system operated as the real center of power within the Soviet state. Nomenklatura appointments extended across party posts, state institutions, economic structures (such as kolkhozes, factories, and planning agencies), as well as culture and education.

Thus, political loyalty and party oversight systematically penetrated all layers of Soviet society (Waller, 1981a).

Centralization and Fear-Based Loyalty under Stalin

From the 1930s onward, the nomenklatura system was organically linked with centralized control and the repressive state apparatus. Under Stalin, personnel policy revolved around the principle of “absolute loyalty”: ideological obedience took precedence over competence. As a result, the nomenklatura became a structure that balanced fear and reward through mechanisms of rotation and purges (Hough, 1979b).

Stalinist repressions served as a consolidating force for the nomenklatura since personal safety was only achievable through loyalty and unconditional execution of top-down directives. This led to the formation of a “loyalty–privilege–immunity” triangle that became the foundation of a fear-based solidarity within the nomenklatura.

The Nomenklatura as a Social Stratum

Over time, the nomenklatura developed into both an administrative elite and a semi-formal social stratum with clear boundaries. Although inclusion and advancement were politically determined, the associated material and symbolic privileges created a deeply stratified society. Examples include special housing, designated stores (spetsmagaziny), sanatoriums, and foreign travel—all contributing to entrenched social differentiation (Ledeneva, 1998a).

This structure limited social mobility and blocked the emergence of alternative elites or independent social dynamics within the USSR. Thus, economic planning and elite construction occurred in parallel within the Soviet system.

The Reproductive Mechanism

One key factor behind the nomenklatura’s endurance was its reproductive character: it produced and promoted cadres from within. Although officially legitimized through party schools and ideological training programs, in practice, advancement depended more on personal networks, patron-client relationships, and loyalty.

This reveals the dominance of informal patronage networks within Soviet governance. Consequently, the nomenklatura facilitated the supremacy of informal politics over formal institutions (Ledeneva, 1998b).

The 1970s–80s: Decline and Bureaucratic Stagnation

The Brezhnev era marked both the peak and the bureaucratic decay of the nomenklatura. The system lost its administrative effectiveness and dynamism, transforming into a rigid yet inefficient apparatus. Reduced cadre rotation, aging officials, and resistance to innovation foreshadowed the system’s eventual collapse (Brown, 2009a).

Nonetheless, despite these weaknesses, the nomenklatura remained the most “prepared” and “experienced” elite group during the post-Soviet transition. After the USSR’s collapse, nomenklatura members retained control in military, security, administrative, and economic institutions, positioning themselves not only as remnants of the past but as architects of the new order.

The Transformation of the Nomenklatura

The political vacuum and institutional chaos following the Soviet Union’s collapse initially appeared to offer opportunities for the rise of new democratic elites. However, developments in the 1990s revealed that the former nomenklatura played a central role in shaping the post-Soviet transition. The nomenklatura elite not only survived but became the leading actors in the political and economic systems (Brown, 2009b).

Retaining Structural Positions

In many post-Soviet republics, the administrative apparatus, law enforcement, and local self-governance continued to be run by old cadres. While this was officially explained by a lack of personnel, weak political alternatives, and a nascent civil society, it was primarily due to the nomenklatura’s control over administrative resources and information flows (Waller, 1981b).

For example, Heydar Aliyev in Azerbaijan, Boris Yeltsin and later Vladimir Putin in Russia, Nursultan Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan, and Islam Karimov in Uzbekistan were all high-ranking figures in the former party or security apparatus. Their knowledge of the state structure, personal networks, and ability to exploit political uncertainty enabled the transfer of structural resources from past to future.

Ideological Flexibility and Rhetorical Adaptation

One of the nomenklatura elite’s most significant advantages was its ideological flexibility. While Soviet rhetoric focused on collectivism, anti-capitalism, and party loyalty, the post-1990s discourse shifted toward “national interests,” “defense of statehood,” “stability,” and “development.” This rhetorical shift was critical for the reproduction of political legitimacy (Brown, 2009c).

For example, Heydar Aliyev in Azerbaijan was portrayed as the “architect of independence” and “national leader,” transforming a former Soviet functionary into the symbolic founder of the post-Soviet state. This repositioning allowed nomenklatura figures to dominate national memory and state ideology, displacing political competition into the moral realm and marginalizing alternative elites (Ledeneva, 1998c).

Rebuilding Patronage Networks

Alongside political change, the economic liberalization and privatization processes of the 1990s opened new opportunities for the former nomenklatura. In many cases, privatization resulted in the concentration of state property in the hands of the former party apparatus and KGB-linked networks (Ledeneva, 1998d).

Traditional top-down patronage was fused with economic patronage: senior officials, former party elites, and security heads created direct links between privatized assets and administrative decision-making. This provided financial stability for authoritarian systems and broadened their social base (Voslensky, 1984b).

Old System under New Faces

The transformation of the Soviet nomenklatura occurred not only structurally and economically, but also visually and symbolically. From Russia and Central Asia to Azerbaijan, post-Soviet leaders presented themselves either as architects of national renewal or as forces of stability preventing chaos. Their identities became synonymous with the state, while political alternatives were branded as “risky,” “inexperienced,” or “puppets of foreign powers” (Brown, 2009d). Under such conditions, the nomenklatura legacy paradoxically became dominant in the construction of national identity.

Ultimately, the former Soviet nomenklatura neither disappeared nor stayed on the margins. It evolved, adapted to new discourses, and continued its role under new names—“new elites,” “oligarchy,” “national leadership”—becoming the institutional carrier of post-Soviet authoritarianism. This evolution ensured state apparatus continuity while creating insurmountable barriers to democratic transformation.

The Role of Nomenklatura Regimes in Authoritarian Resilience

The stagnation of democratic transitions, the longevity of authoritarianism, and the weakening of political competition in the post-Soviet space cannot be explained by legal-institutional factors alone. One of the deep-rooted structural forces behind these trends is the continued political presence and adaptive capacity of the former Soviet nomenklatura.

As Seen in the Visual, the Contribution of the Nomenklatura to the Resilience of Authoritarian Regimes Can Be Explained at Four Main Functional Levels: Administrative Capabilities, Legitimacy Rhetoric, Relationship with the Repressive Apparatus, and Technocratic Synthesis

Administrative Resources

During the Soviet era, the nomenklatura elite worked within a highly centralized planning system, gaining unique expertise in strategic management and information control. This administrative "knowledge capital" was repeatedly utilized in the post-Soviet period—especially in the reorganization of administrative apparatuses, emergency decision-making, and governance under extraordinary circumstances (Hough, 1979c).

In addition, the personal and informal networks carried by this stratum—established among regional party leaders, security agencies, and industrial directors—played a crucial role in rebuilding bureaucratic patronage systems. As a result, new regimes constructed post-Soviet governance models based on personal dependencies and reward mechanisms under the guise of "modern state management" (Ledeneva, 1998d).

Loyalty Networks and the Discourse of “Stability”

The nomenklatura elite justified its presence with rhetoric such as "experience," "state tradition," and "guarantor of stability," while portraying alternative political forces as either dangerous or unprofessional (Brown, 2009e). This serves to marginalize political opponents and ensure psychological loyalty among citizens.

In Azerbaijan, this discourse is particularly visible. Heydar Aliyev and his son Ilham Aliyev portray themselves as experienced figures who understand the system and embody state-building continuity. Opposition forces, on the other hand, are branded with labels such as “inexperience,” “openness to foreign influence,” and “desire to cause disorder.” In this way, the regime claims both moral and technocratic superiority.

Symbiosis with Security Institutions

A core element of the resilience of nomenklatura regimes lies in their long-standing and close relationships with the repressive apparatus. The mutual trust and functional synchrony established between the Party and the KGB during the Soviet era have continued in the post-Soviet context—most visibly in Russia and Azerbaijan.

Vladimir Putin's background as a former KGB officer and his administration’s centralization of political power in the security apparatus is a classic illustration of this model (Ledeneva, 1998e). In Azerbaijan, since the late 1990s, the dominance of former KGB operatives and party functionaries in the judicial-legal system has reinforced the trend toward the legalization of repression—what some call "authoritarian rule of law" (Marc Weinstein, 2023).

This structural model normalizes and institutionalizes repression, transforming it from a mere tool of fear into a legitimate mechanism of governance.

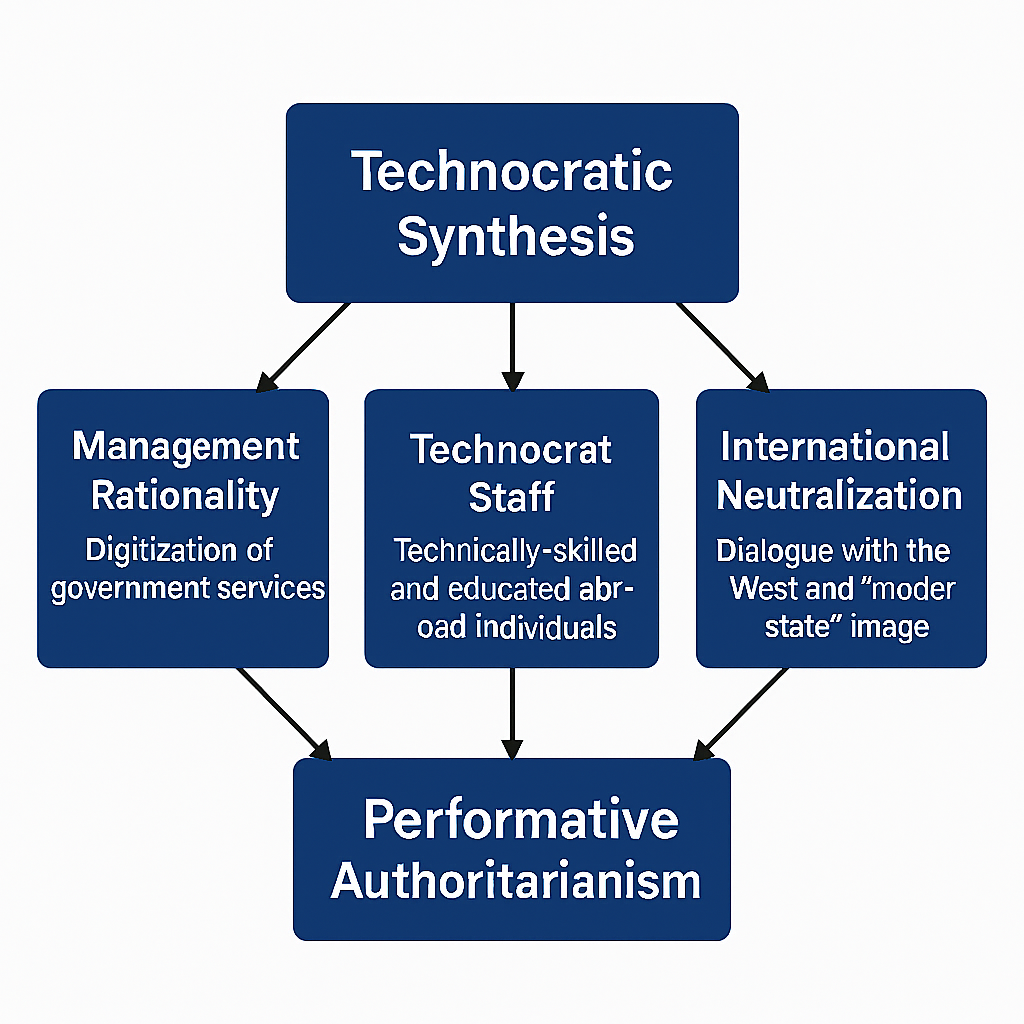

Technocratic Synthesis and Authoritarian Modernization

Authoritarian regimes in the post-Soviet space have not only preserved the administrative structures inherited from the Soviet era but have also reformatted these structures through a synthesis with modern management technologies, communication strategies, and technological control tools. This process—the fusion of institutional and ideological legacies with contemporary technocratic instruments—has contributed to the emergence of performative authoritarianism (Gerschewski, 2013).

Governance Rationality and Technocratic Hegemony

The new-generation nomenklatura no longer functions solely on the basis of political loyalty. By adopting technocratic discourses such as "governance efficiency," "digital services," and "sustainable development," it creates an image of rationality for both domestic and international audiences (Schedler, 2006).

This technocratic rationality manifests in three key ways:

1. Digitalization of Public Services

Inspired by relatively democratic post-Soviet countries like Estonia and Georgia, authoritarian regimes have begun to implement digital governance tools, creating the image of “modernized” public services. Azerbaijan’s ASAN Xidmət model and Kazakhstan’s “eGov.kz” platform are examples of such efforts.

2. Rise of Technocratic Cadres

Individuals with technical expertise, Western education, and experience working with international organizations are increasingly promoted within presidential administrations and economic institutions. However, these promotions often occur within a framework of technocratic legitimacy conditioned by political loyalty (Frye, 2010). This blurs the distinction between “appointed experts” and “independent professionals.”

3. International Neutralization Strategy

Through technocratic discourse, authoritarian regimes aim to project an image of being "open to reform" and a "modern state" in their relations with Western institutions. This strategy provides them with a buffer against criticism: issues related to human rights and democratic institutions are reframed as mere technical matters (Marc F. Plattner, 2019).

The Performative Framework of Digital Authoritarianism

This diagram illustrates that authoritarian regimes use modern technology, digitalization, and foreign-educated technocrats as tools to create an “image of reform.” While these elements do not actually ensure the democratization of the regime, they are performatively employed to strengthen its legitimacy both domestically and internationally. The resulting system, in the end, is not one of genuinely effective governance, but rather a form of authoritarianism where “governance appears to be effective.”

The technocratic synthesis simultaneously normalizes the use of digital surveillance technologies. Authoritarian regimes use these technologies to:

- Monitor public discontent,

- Direct the flow of information,

- Suppress online activism (Polyakova, 2019).

For example, Russia and Azerbaijan have developed advanced technological infrastructures in this domain: automated social media monitoring systems, Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technologies, and AI-powered facial recognition and social profiling mechanisms are clear manifestations of performative authoritarianism.

This has turned into a technological legitimacy argument that ostensibly proves governance capability. In other words, a system is created that says to citizens, “Look, we provide you with fast services and maintain stability,” while at the same time surveilling and controlling everyone’s behavior (Gunitsky, 2015).

Conclusion of Part I

The post-Soviet nomenklatura maintains its status as a “resilient and adaptive alternative to democracy” through its institutionalized administrative experience, patrimonial networks, symbiosis with the legal system, and synthesis with technological infrastructure.

If hopes for democratic transition are limited only to formal elections, constitutional amendments, or party competition, these regimes can simply rebrand themselves while continuing to operate in substance. Therefore, genuine democratic transformation must occur simultaneously in the following spheres:

- Social: Promoting civic participation and critical thinking;

- Ideological: Deconstructing the dominant discourse and fostering alternative narratives;

- Institutional: Establishing transparent governance systems free of old cadres and patronage networks;

- Technological: Subjecting digital surveillance to normative frameworks and strengthening public oversight.

Otherwise, transition processes will remain democratic in form but substantively represent a modernized format of nomenklatura authoritarianism—and with few exceptions, this remains a defining pattern across the post-Soviet space.

References:

Jerry F. Hough, (a) How the Soviet Union Is Governed (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979). https://archive.org/details/howsovietunionis0000houg

Michael Voslensky (a) Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class (New York: Doubleday, 1984). https://www.amazon.com/Nomenklatura-Soviet-Ruling-Michael-Voslensky/dp/0385176570

Waller, Michael. 1981a. [Review of Political Culture and Soviet Politics, by S. White]. The Slavonic and East European Review, 59(1), 132–134. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4208242

Jerry F. Hough, (b) How the Soviet Union Is Governed (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979). https://archive.org/details/howsovietunionis0000houg

Alena V. Ledeneva (a) Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/sociology/political-sociology/russias-economy-favours-blat-networking-and-informal-exchange?format=PB&isbn=9780521627436

Archie Brown, (a) The Rise and Fall of Communism (London: Bodley Head, 2009). https://www.cvs.edu.in/upload/Archie%20Brown%20-%20The%20Rise%20and%20Fall%20of%20Communism%20(2009).pdf

Archie Brown, (b) The Rise and Fall of Communism (London: Bodley Head, 2009). https://www.cvs.edu.in/upload/Archie%20Brown%20-%20The%20Rise%20and%20Fall%20of%20Communism%20(2009).pdf

Waller, Michael. 1981b. [Review of Political Culture and Soviet Politics, by S. White]. The Slavonic and East European Review, 59(1), 132–134. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4208242

Archie Brown, (c) The Rise and Fall of Communism (London: Bodley Head, 2009). https://www.cvs.edu.in/upload/Archie%20Brown%20-%20The%20Rise%20and%20Fall%20of%20Communism%20(2009).pdf

Alena V. Ledeneva (b) Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/sociology/political-sociology/russias-economy-favours-blat-networking-and-informal-exchange?format=PB&isbn=9780521627436

Michael Voslensky (b) Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class (New York: Doubleday, 1984). https://www.amazon.com/Nomenklatura-Soviet-Ruling-Michael-Voslensky/dp/0385176570

Archie Brown, (d) The Rise and Fall of Communism (London: Bodley Head, 2009). https://www.cvs.edu.in/upload/Archie%20Brown%20-%20The%20Rise%20and%20Fall%20of%20Communism%20(2009).pdf

Jerry F. Hough, (c) How the Soviet Union Is Governed (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979). https://archive.org/details/howsovietunionis0000houg

Alena V. Ledeneva (d) Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/sociology/political-sociology/russias-economy-favours-blat-networking-and-informal-exchange?format=PB&isbn=9780521627436

Archie Brown, (e) The Rise and Fall of Communism (London: Bodley Head, 2009). https://www.cvs.edu.in/upload/Archie%20Brown%20-%20The%20Rise%20and%20Fall%20of%20Communism%20(2009).pdf

Marc Weinstein,2023. Autocratic Legalism and the Threat to Academic Freedom: Are We Learning the Right Lessons from Europe? https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/Weinstein_Blanchard_JAF14.pdf

Alena V. Ledeneva (e) Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking and Informal Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/sociology/political-sociology/russias-economy-favours-blat-networking-and-informal-exchange?format=PB&isbn=9780521627436

Gerschewski, J. (2013). The Three Pillars of Stability: Legitimation, Repression, and Co-optation. Democratization.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.738860

Schedler, A. (2006). The Logic of Electoral Authoritarianism. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

https://www.rienner.com/title/The_Logic_of_Electoral_Authoritarianism

Frye, T. (2010). Building States and Markets after Communism. Cambridge University Press. https://assets.cambridge.org/97805217/34622/frontmatter/9780521734622_frontmatter.pdf

Marc F. Plattner. (2019). Why Illiberal Democracy is on the Rise. Journal of Democracy.

https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/illiberal-democracy-and-the-struggle-on-the-right/

Polyakova, A., & Meserole, C. (2019). Exporting Digital Authoritarianism. Brookings Institution.

https://policycommons.net/artifacts/3527460/exporting-digital-authoritarianism/4328250/

Gunitsky, S. (2015). Corrupting the Cyber-Commons: Social Media as a Tool of Autocratic Stability. Perspectives on Politics.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/corrupting-the-cybercommons-social-media-as-a-tool-of-autocratic-stability/CD2CCFAB91935ED3E533B2CBB3F8A4F5