Introduction

This brief is addressing the tendency which becomes increasingly alerting in an environment where misinformation outweighs facts. Shedding light on pro-Russian and anti-Western narrative proxies, media strategies, narratives, the piece brings up viable solutions based on concise analysis of recent political developments in Southeast Europe. Consequently, the policy brief presented by KHAR Center put forward the structural and relative policy options for countering Kremlin-led propaganda that targets Euro-Atlantic integration of the region.

Perhaps, after the end of the Cold War among the ideologically polarized world powers and after the period when ideological propaganda was a legitimate instrument to direct and regulate masses, the propaganda again became part of the modus operandi of illiberal or backsliding democracies and authoritarian regimes on a global scale. However, in the current period of history, propaganda is largely not used as it was used before. Entailing to disinformation, misleading information, and socio-political myths, propaganda gained new patterns and new shape. Nonetheless, previously, the majority were commonly associating it with inflammatory speech and/or baseless statements made by totalitarian leaders, current studies conducted on modern tendencies of propaganda and mis(dis)information do not invalidate that propaganda actually can be based on facts. However, the facts are presented in a way that they trigger a desired response. (“Guides: Evaluating Information: Propaganda, Misinformation, Disinformation,” n.d.) Complementarily, the propaganda can also be conceptualized as systematic dissemination of biased and misleading information in order to advance a particular cause or perspective, as described by Oxford English Dictionary. (“Propaganda | Oxford English Dictionary,” n.d.)

For the clarity of this brief’s content, it would also be pertinent to mention that propaganda has been used as an umbrella term for misleading information, disinformation, factual manipulation, and socio-political myths.

Particularly examining Anti-Western Propaganda on the EU accession, this policy brief aims to shed light on Kremlin-backed propaganda and misinformation, investigating pro-Russian and anti-Western narrative proxies, media strategies, and discourses currently and previously employed in Southeast Europe. Even though the EU’s reputation remains moderate and high in respect of various criteria in Southeast Europe, the decay of unipolar or uni-multipolar world order and drastic shift in U.S. policies towards aiding civil society and media, can expose the information landscape of the region being vulnerable to Russia-backed propaganda. (“USA: Trump’s Foreign Aid Freeze Throws Journalism Around the World Into Chaos” 2025)

Thus, in this policy brief, we intend to succinctly research the peculiarities of Kremlin-led propaganda affecting the public opinion regarding the EU accession of Southeast European countries, and put forward a set of relevant solution-oriented recommendations.

Effects of Russian Propaganda on Southeast European Countries

Russia’s one of the apparent strategic interests in the region is to halt the EU and NATO membership of Southeast European countries. (Salvo & de Leon 2018) This interest allegedly took on its boldest shade with the 2017 attempt of a coup d'état in Montenegro aimed to prevent the country’s NATO accession. (BBC News 2019) (Salvo & de Leon, 2018) Nevertheless, the coup was not successful and Montenegro joined the alliance, the Kremlin explicitly demonstrated that it is not likely to tolerate any sort of substantial EU and NATO integration of Southeast European countries. (Salvo & de Leon 2018) Russia’s anti-West strategies in the Western Balkans can be categorized in four divisions: (i) usage of media to spread pro-Kremlin and anti-Western ideas, (ii) supporting paramilitary units in the region, (iii) supporting politicians and political organizations (both far-left and far-right) that take hardline position towards collective West, (iv) leveraging economic ties for political blackmailing. Hence, throughout the years, Moscow utilized various tricks and tactics to push for the goal mentioned above, including but not limited to pausing gas supplies, banning agro-food exports, deploying Cossack paramilitary groups, allegedly organizing a coup, maintaining disinformation campaigns, supporting nationalist movements and organizations. (Secrieru 2019) Within the given scope of the particular policy brief, I plan to zoom in to the propaganda and misinformation dimension of Moscow-led intervention in the Western Balkans.

In general, it has to be mentioned that Russia’s anti-West propaganda is being produced in both top-down and bottom-up ways, as the Kremlin simultaneously tended to make agreements with anti-West governments and parties of the region to form formal alliances against Euro-Atlantic integration alongside creating and sponsoring troll networks, disseminating unauthored “researches”, launching social media campaigns serving to the same purpose. Blurring the line between facts and opinions, Russian propaganda proxies maintain the cycles of information production, i.e., disseminated unauthored “research” pieces are being cited in pro-Kremlin media outlets and social media posts and vice versa. (Metodieva 2019) Furthermore, the examples of a top-down approach of enforcing anti-West narratives can be the formal agreement on “military neutrality” signed by Putin’s United Russia Party and anti-NATO political parties of Southeast European region in 2016, launching the media outlet (“Sputnik”) which disproportionally and selectively focuses on failures of Western institutions, romanticizes the Slavic brotherhood, lionizes Putin’s image, and disseminates conflict fueling narratives as “islamic extremism” among Bosnians or “Greater Albania” arisen among Kosovo, Albania, and some parts of North Macedonia. (Karcic 2022) According to research conducted by raskrinkavanje.ba, a fact-checking media outlet, solely in the first year of Sputnik Serbia’s operation, 36 uses of disinformation were found in 16 articles, while more than 100 articles were depicting positive bias towards Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Serb leader Milorad Dodik. (Karcic 2022)

Overall, three key events/tendencies will well illustrate Russia’s willingness and abilities to manipulate public opinion in the Balkans. The first of these events is the referendum held in North Macedonia in September 2018 as a condition of the Prespa Agreement signed with Greece. The referendum was decisive in renaming the country and opening the path towards NATO membership, as persisting conflict with Greece was hampering this process. Despite the fact that the referendum had a 92 % approval rate, only ⅓ of voters took part in voting due to a massive boycott campaign. United Macedonia Party, pro-Russian organizations and groups backed the boycott calling it deviation from national interests and “betrayal”. During the pre-voting period, hundreds of automated bots, trolls, anonymous news websites, and social media pages spreading anti-West and anti-NATO messages were launched, followed by warnings by Russian officials of new potential conflicts in case North Macedonia joins NATO. (Metodieva 2019)

The second tendency worth mentioning is Russia’s political and media presence in Serbia related to the Kosovo issue. Russia uses Serbian media landscape as a stronghold in the Balkans, as it made huge investments in the energy and media sectors of the latter. Pro-Russian and anti-Western sentiments are circulated through Russia-backed media outlets addressing all former Yugoslavian countries. (Metodieva 2019)

The third tendency on the list is Russia’s unanimous support for Milorad Dodik, president of Republika Srpska (constituting entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina). Russia shows continuous support for Dodik’s government, as rising nationalism in Republika Srpska substantially hampers Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Euro-integration. For this purpose Russia uses local media to spread anti-West and anti-NATO messages, alongside utilizing Serbia’s media landscape for the same cause. (Metodieva 2019)

Countering the Propaganda: Policy Options and Recommendations

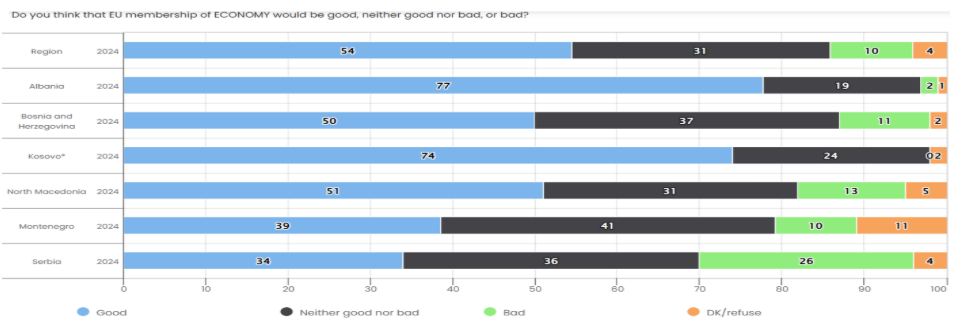

Chart 1. © Regional Cooperation Council: Balkan Public Barometer - https://www.rcc.int/balkanbarometer/results/2/public

Chart 1. © Regional Cooperation Council: Balkan Public Barometer - https://www.rcc.int/balkanbarometer/results/2/public

Although public perception of integrating national economies into the EU is quite satisfactory across the region, with 85% of respondents from six countries answering that EU membership for the economy would not be a bad thing, the vulnerabilities of the media landscape of the region should make us cautious (Chart 1). As the region lacks substantial fact-checking missions, alongside persisting structural reasons caused by the EU and NATO bureaucracy, public opinion may be volatile in upcoming years. Plus, one should expect and already witness the decrease in the United States’ interests in aiding civil society and media overseas, which is likely to reflect itself in shrinking space for the civic sector. To the end of tackling repercussions and preventing harm that may occur as a result of manipulation of public opinion, two policy options and several recommendations may be considered.

Structural (Radical) Solution: Accelerating EU and NATO accession for Southeast Europe

Over the years, the journey to becoming a member state of the EU and NATO has become increasingly elusive. However, the lengthy nature of this process seems to foster mistrust toward the collective West, demotivating not only governments but also the general public. Addressing this structural cause of mistrust can weaken the propaganda that shapes aspirations toward the West among both the masses and governments. The expedited provision of EU member state candidacy status to certain Eastern Partnership countries in response to Russia’s expansionism underscored the importance of political will in the EU accession process. Putting it in simple words, it made it clear that accelerating the overall process is possible. Finally, Southeast European states should see at least some interim tangible results if not full membership.

Relative Solution: Enhancing Capacities of local Civil Society and Media to Tackle the Propaganda

Enhancing the capacities of local civil society and media will be a relative and long-term solution of the problem. This includes well-measured and designed capacity building programs for civil society and media actors enabling them to possess a fact-checking function. Also, increasing the number of quality fact-checking media entities can also contribute to the solution.

A set of policy recommendations can be put forward based on the policy options described above:

- Intensifying negotiations with the Southeast European states’ representatives to see possibilities of accelerating the EU and NATO membership

- Granting interim achievements and status to Southeast European states before their membership with economic, trade, and security benefits.

- Offering tangible and respectively increasing security guarantees alongside the progress made in the membership process.

- Enhancing the capacities of local civil society and media to combat propaganda and misinformation.

- Increasing the number of quality fact-checking media organizations in the region.

Final Remarks

In the nutshell, Russia’s direct manipulative interventions and narrative proxies may play a significant role in hampering the region’s integration into the Euro-Atlantic zone. In an increasingly vulnerable environment, this manipulation may cause severe repercussions not only limited to stagnation of EU integration, but also ignition of frozen conflicts and enmities. That is why the collective effort of EU, NATO, national governments, local civil societies and media organizations is needed to prevent the worst scenarios.

References

BBC News. 2019. “Montenegro Jails ‘Russian Coup Plot’ Leaders.” May 9, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-48212435.

“Guides: Evaluating Information: Propaganda, Misinformation, Disinformation” n.d. https://guides.library.jhu.edu/evaluate/propaganda-vs-misinformation.

Karcic, Harun. 2022. “Soviet-era Disinformation Campaign Makes a Comeback in the Balkans | Al Sharq Strategic Research.” Al Sharq Strategic Research. April 5, 2022. https://research.sharqforum.org/2022/02/22/disinformation-campaign/.

“Propaganda | Oxford English Dictionary.” n.d. https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?q=propaganda.

Metodieva, A. 2019. RUSSIAN NARRATIVE PROXIES IN THE WESTERN BALKANS. German Marshall Fund of the United States.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep21239.

Salvo, D., & de Leon, S. 2018. Russia’s Efforts to Destabilize Bosnia and Herzegovina.

German Marshall Fund of the United States.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep18769.

Secrieru, S. 2019. RUSSIA IN THE WESTERN BALKANS: Tactical wins, strategic setbacks. European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS).

http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep21130.

“USA: Trump’s Foreign Aid Freeze Throws Journalism Around the World Into Chaos.” 2025. RSF. March 2, 2025. https://rsf.org/en/usa-trump-s-foreign-aid-freeze-throws-journalism-around-world-chaos.