✍️ Elman Fattah – Director of the KHAR Center

During 2024–2025, the intensive negotiations between Azerbaijan and Armenia toward signing a peace agreement have been presented as a real opportunity to end the decades-long conflict in the South Caucasus. However, this peace cannot be explained solely through the internal will or bilateral determination of the two states. On the contrary, this process must be evaluated against the backdrop of shifting geopolitical configurations in the region, new confrontations among global power centers, and the conflicting interests of various actors (Russia, Turkey, the European Union, the United States).

The purpose of this analysis is to assess the viability of peace between Azerbaijan and Armenia by examining the new opportunities, the looming risks, and the role of regional powers—ultimately asking how real and sustainable such a peace can be.

Confrontation with Russia: Azerbaijan’s “Post-Moscow” Orientation

The tensions observed in Azerbaijan-Russia relations during 2024–2025 cannot be explained merely as diplomatic misunderstandings between two states. Rather, this tension is closely linked to the collapse of post-imperial relations, structural distrust toward the Kremlin, and the Azerbaijani government’s new geopolitical strategy.

Notably, the killing of two Azerbaijanis by Russian police in Yekaterinburg at the end of 2024, and Baku’s sharp reaction—including summoning the Russian ambassador, canceling Russian cultural events, and suspending the operations of "Sputnik Azerbaijan"—has evolved beyond a protocol crisis into a symbol of strategic distrust (Elman Fattah, KHAR Center, 2025). This escalation also revealed that the "brotherhood narrative" in Azerbaijani society and among the political elite regarding Russia is becoming obsolete.

Rejection of Russian Mediation:

Following the Second Karabakh War in 2020, Azerbaijan initially accepted the deployment of Russian peacekeepers, temporarily recognizing Moscow’s role as the "geopolitical hegemon" in the region. However, the implementation of that agreement—particularly Russia’s perceived partiality, accusations of indirect support for Armenian separatists, the restoration of Azerbaijani control over Karabakh in late 2023, and the subsequent withdrawal of Russian forces—led Baku to fundamentally reassess its strategy toward Moscow.

This is more than a tactical shift—it signals that Azerbaijan is preparing for a new phase in regional policy, one characterized by a “post-Moscow configuration.” Within this framework, Baku aims to present itself as a sovereign, rational, multi-vector, and norm-based power in contrast to the Russian model.

Azerbaijan’s New Status – Role of “Stabilizing Actor”:

For Azerbaijan, confrontation with Russia is not only about reducing geopolitical threats but also about reformatting its international standing. Official Baku aspires to establish a new security order in the South Caucasus, build a legal status quo based on normative principles, and position itself as a “stabilizing and decision-making actor” in the eyes of both Western and regional powers (Stronski, 2023). This role encompasses economic (energy supply, transport corridors), security (anti-terrorism, border stability), and diplomatic (mediation, regulation) dimensions.

If the peace agreement with Armenia is signed under Western mediation, it would symbolize the end of Russian hegemony and mark a significant normative turning point. Azerbaijan’s initiative in driving this process positions it as an alternative to the Kremlin—a strategic and ideological defeat for Russia.

Turkey–Armenia Rapprochement: Historical Breakthrough or Balancing Act?

In recent years, the resumption of diplomatic contacts between Turkey and Armenia has created an important regional context for the Azerbaijan–Armenia peace process. Historically, the closure of the border in 1993 and the absence of diplomatic relations created a deep political rift between the two countries. While the 2009 Zurich Protocols aimed to normalize relations, the process ultimately collapsed due to internal political resistance in Turkey and Azerbaijan’s sharp reaction (Chatham House, 2010). However, the situation changed significantly after the 2020 Karabakh war.

A New Configuration – The “Post-Karabakh” Era and Diplomatic Opportunities:

Azerbaijan’s military victory and restored territorial control in the 2020 war altered the region’s political status quo. This created an opportunity for Turkey to reconsider its relations with Armenia, as cooperation could now occur in coordination with Baku and without causing Azerbaijani discomfort (Cornell, 2025). Since early 2022, direct meetings between Turkish and Armenian special envoys, the resumption of reciprocal flights, and negotiations over humanitarian-based border crossings have signaled a new phase (ICG, 2025).

For Armenia: An Alternative Path to Security and Integration:

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Pashinyan, rapprochement with Turkey serves both as a route to economic access and a diplomatic alternative to the Russian security model. Public dissatisfaction with Russian influence has grown in Armenia in recent years, and normalization with Turkey is viewed as a step toward broader integration with Western institutions and as a strategy to consolidate domestic support (Giragosian, 2023). This rapprochement aligns with Armenia’s pursuit of “blockade-free diplomacy.”

Turkey’s Strategic Interests: Integration and Mediation:

For Turkey, restoring relations with Armenia is not merely a bilateral issue but a geopolitical strategy. First, it strengthens Turkey’s role as a reliable regional partner in the South Caucasus. Second, it enhances Turkey’s image as a “regional stabilizing power” in the eyes of the West—particularly useful amid its growing geopolitical role in the context of the war in Ukraine (Wilson Center, 2024). Furthermore, this opening allows Ankara to build a diplomatically balanced game involving both Iran and Russia via Armenia.

Azerbaijan’s View: Benefits and Concerns:

For Azerbaijan, Turkey–Armenia rapprochement is a double-edged development. On one hand, it can contribute to deeper regional integration, the opening of communication channels, and overall normalization. On the other hand, if Ankara’s regional policy becomes less “Azerbaijan-centric,” it could shift strategic balances. Rapid development in Ankara–Yerevan ties might weaken the “special relationship” between Baku and Ankara—especially if Armenia’s normalization proceeds independently of Azerbaijan’s input. To mitigate this risk, Turkish officials consistently emphasize that the normalization process with Armenia is carried out “in coordination with Azerbaijan” (TRT World, 2022). Nonetheless, there is no doubt that Baku harbors concerns that deepening Turkey–Armenia ties might undermine Azerbaijan’s exclusive geopolitical priority status in the South Caucasus.

Armenia’s Strategic Pivot to the West and Its Impact on Peace

The Armenian government under Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has, in recent years, openly chosen to distance itself from Russia’s security architecture. This shift has manifested in several key directions: deepening distrust toward the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), intensified cooperation with Western structures—particularly the European Union (EU) and the United States—and public declarations recognizing Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

Moving Away from CSTO and Moscow:

Armenia’s critical rhetoric toward the CSTO intensified after the organization's refusal to intervene during the September 2022 border clashes with Azerbaijan. In Armenian society and political circles, the CSTO’s credibility as a “security guarantor” was severely damaged, and the benefits of membership were called into question. In 2023, the Armenian government refused to host CSTO military drills, and by early 2024, openly raised the possibility of withdrawing from the organization (Eurasianet, 2024).

Simultaneously, Armenia accelerated its engagement with Western institutions. Under the “Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement” with the EU, commitments to political and legal reforms have increased. The deployment of the EU Monitoring Mission (EUMA) along the Armenia–Azerbaijan border in 2023–2024 and deepening cooperation with NATO marked a turning point in Armenia’s security concept (EUMA Contracts 2024–2025).

Additionally, in 2024, the Armenian government officially recognized Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, signaling its acceptance of post-war realities and a political will for peace. This declaration, which followed earlier statements made by Pashinyan in Prague in October 2022, took on a more concrete character (CivilNet, 2024).

The Peace Agreement as Armenia’s Strategy for Salvation:

Against the backdrop of these transformations, Armenia views the peace agreement not only as a way to normalize relations with Azerbaijan but also as a legal and political exit from Russian influence. In this sense, peace becomes a kind of “act of salvation” for Yerevan—an end to the conflict and the foundation for a new geopolitical orientation (CMF, 2024).

Although this strategy does not fully align with Azerbaijan’s interests—Baku supports weakening Russian influence but remains cautious about Armenia gaining a stronger foothold in Western platforms—it nevertheless creates a rare historical opportunity for a mutually beneficial peace. For Azerbaijan, this is a crucial chance to secure a legal-status agreement under Western mediation and to keep Armenia distanced from new military alliances.

The Possibility of Peace: A Real but Fragile Hope

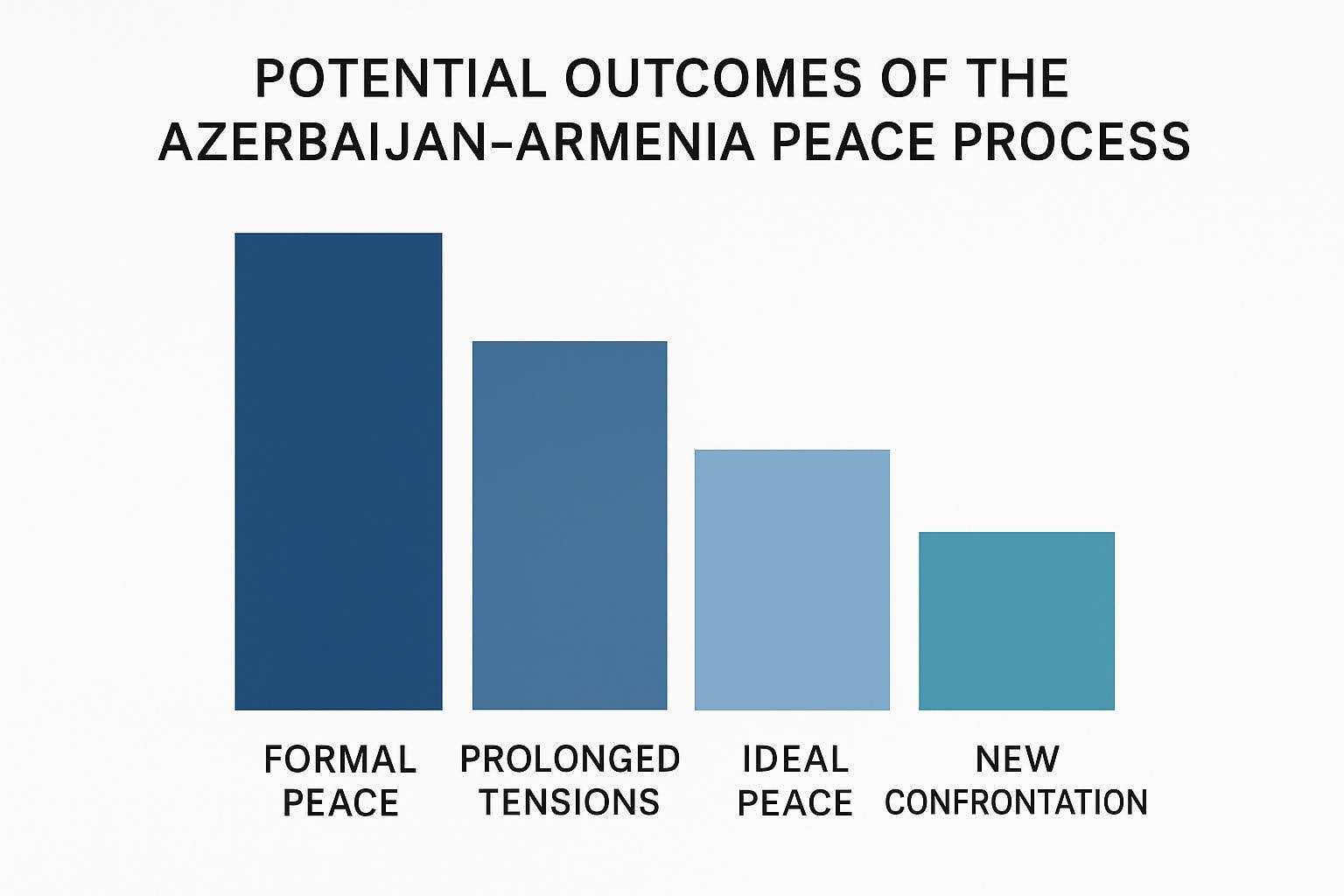

In the diagram above, I visualized four key assumptions related to the Armenia–Azerbaijan peace process:

- Ideal Peace – A durable, legally grounded agreement with public legitimacy.

- Formal Peace – An agreement signed at the political leadership level but weakly implemented and ineffective in creating real change.

- Deferred Tension – Despite a peace agreement, tensions reemerge due to internal resistance and regional pressures.

- New Confrontation – A total failure of the peace process, leading to renewed military or diplomatic crises.

The current stage of the peace process seems somewhat promising: the parties are keeping diplomatic channels open, some agreements have been reached on core issues, and international mediators are playing an active role. However, despite these positive signs, achieving a sustainable, legally binding, and practically impactful peace faces serious obstacles. These challenges are not only technical in nature but also structural and political.

Institutional Weakness and Democratic Deficit

Although Azerbaijan and Armenia have different political systems, both face problems with institutional resilience. Azerbaijan operates under a rigid authoritarian system that systematically suppresses political pluralism and civil society (Freedom House, 2024). Armenia, while seemingly more democratized, suffers from weak institutions and a fragmented political system, which undermine consistency and effectiveness in decision-making (International IDEA, 2023). These weaknesses impair the transparency, accountability, and public legitimacy of peace negotiations. In both societies, public consensus around peace is weak.

Domestic Political Resistance and Revanchist Forces

Strong internal opposition to the peace process exists in both countries. In Azerbaijan, a hostile narrative in official rhetoric, coupled with militarist propaganda by pro-government media, has fueled deep public suspicion toward “compromise” and triggered nationalist reactions. This increases the likelihood of harsh backlash against potential concessions.

In Armenia, the trauma of defeat in the 2020 war, entrenched conservative structures within the military and the church, and electoral opposition to Prime Minister Pashinyan—particularly from political blocs surrounding former presidents (Kocharyan and Sargsyan)—pose clear resistance to the process (Giragosian, 2023).

Absence of Security Guarantees

The lack of neutral, functional, and internationally trusted security mechanisms for implementing the peace agreement creates serious gaps in enforcement and monitoring (ICG, 2023). While the EU and OSCE have deployed observation missions, their mandates are limited, and their legal authority is weak. Although the US and EU act as mediators, they do not offer peacekeeping forces or mandatory enforcement mechanisms. This risks turning the peace agreement into an ambiguous and reversible process after it is signed.

Regional and Global Rivalry, Clashing Interests

The South Caucasus currently lies at the crossroads of multiple power centers—Russia, Iran, Turkey, the EU, and the US—yet lacks a shared security architecture. This increases the risk that peace will become not a local initiative, but a fragment of broader global strategic confrontation.

Russia views the South Caucasus as its “traditional sphere of influence” and is fundamentally opposed to Western consolidation in the region. A peace agreement brokered by the EU and US would deal a serious blow to the Kremlin’s regional prestige. This could push Russia toward destructive behavior, including military coordination with Armenia or Iran (Kucera, RFE/RL, 2024).

Iran is especially sensitive about the Zangezur Corridor issue. New transit routes formed via the Turkey-Azerbaijan tandem are perceived as a threat to Tehran’s regional role. As a result, Iran occasionally applies pressure through military exercises and aggressive border rhetoric.

The West, in turn, views peace in the region through the lens of democratization and energy security. However, the West's interests and tools in this region are not sufficiently coordinated, which limits its influence over the process.

A Historic Opportunity or an Illusion?

Today, the signing of peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan is presented as both a realistic and historic opportunity. However, for this opportunity to translate into tangible and lasting results, the parties must possess not only technical agreements but also political will, public consensus, and institutional guarantees. The current configuration does not allow us to classify the peace process strictly as an idealist “utopia” or as a purely tactical maneuver aimed at short-term gains. Rather, it represents a delicate balance—both a regional transformation opportunity and a potential entry point for new confrontations.

If signed, the peace agreement will not merely end the conflict—it will mark the foundation of a new security and cooperation architecture in the region. In this context, peace can be evaluated in three key dimensions:

- Development-Oriented Peace – The restoration of regional communications, increased economic cooperation, and new opportunities for energy logistics. Projects such as the Zangezur Corridor (Syunik) and the Kars–Yerevan railway route could come to the fore.

- Political Transformation – Peace could create new modernization challenges for the internal political systems of both Armenia and Azerbaijan, including democratization, legal reforms, and the development of a peace culture.

- Geopolitical Reconfiguration – A peace agreement may lay the groundwork for an alternative regional order to counter Russian influence—especially through mediation by the EU and Turkey.

Toward a Conflict-Free Caucasus: Historic Opportunity

If successful, Armenia–Azerbaijan peace could be the first real post-Soviet transition to a normative order in the Caucasus based on mutual recognition and a non-military status quo. This would not be limited to the normalization of relations between the two countries—it could also accelerate Armenia’s regional integration, enhance Azerbaijan’s international legitimacy, and stabilize Turkey–Armenia relations. At the same time, peace would create a more stable neighborhood for Georgia, increasing overall political and economic security in the region.

Deferred Conflicts

On the other hand, if peace remains merely formal—reduced to geopolitical maneuvering by political elites and short-term diplomatic gains—it will eventually collide with reality. If the post-war Karabakh issue remains unresolved, if there are gaps in civil rights, communication channels, and security mechanisms, the "peace agreement" will remain on paper and serve only to incubate future tensions.

Moreover, both Russia and Iran possess overt or covert sabotage potential against this process, indicating that peace must be negotiated not just between the parties but also with regional powers. This calls for diplomacy to move beyond the classical “bilateral format” toward more complex, multi-layered negotiations.

Proactive Planning

If Baku and Yerevan treat peace not just as a tool for gaining strategic advantage or securing Western support, but as a necessary foundation for internal stability and regional prosperity, transformation is possible. This requires the following conditions:

- Public Legitimacy – Peace agreements must be shared not only between leaders but also among civil societies and political parties, ensuring public support. However, this appears nearly impossible in Azerbaijan, where the ruling hardline authoritarian regime has completely dismantled opposition parties and independent civil society (KHAR Center, 2025).

- Cross-Border Cooperation – The real value of peace should be felt in daily life through economic, energy, and infrastructure projects.

- International Guarantees – Within the framework of the EU or NATO, mechanisms should be established to monitor and enforce the peace, with legal consequences in the event of violations.

- Education and Historical Narrative Reform – Both countries must take long-term transformative steps to ensure that younger generations perceive each other not as enemies, but as neighbors and partners.

Conclusion

If achieved, Armenia–Azerbaijan peace will not be merely a diplomatic document. It will be a vision for the future built upon a century of three wars, an unending history of violence, post-imperial zones of influence, and ethno-nationalist narratives. This peace will either fully transform the region—or go down in history as a prologue to a new generation of conflicts. The choice depends on the will of the parties and the accompanying international community.

Final Reflection

The prospect of a peace agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia lies today at the heart of deep transformations unfolding in the South Caucasus. This prospect holds historical significance not only for normalizing relations between the two states but also for addressing long-standing political, economic, and normative vacuums created by protracted conflicts in the region.

However, this opportunity is not guaranteed—on the contrary, it is surrounded by exploitable risks and tendencies toward postponement. The current peace agenda must be assessed in the context of both opportunities and challenges.

Tensions in Azerbaijan’s relations with Russia have pushed Baku to be more open to peace under Western mediation, while the launch of rapprochement between Turkey and Armenia has created a key opportunity for regional stability. Armenia’s pivot away from Russia and toward alternative security and diplomatic channels also promotes peace as a geopolitical necessity.

Yet alongside these opportunities, there are serious structural barriers that weaken the durability of the process: hard authoritarianism and militarism in Azerbaijan, weak democratic institutions in Armenia, unstable public opinion on peace, the potential rise of revanchist populism, and the absence of international security guarantees—all of which may seriously hinder transforming this agreement into a long-term stability project.

If signed, peace will signify more than the end of war. It will represent the emergence of a new geopolitical reality—interregional connectivity, economic integration, and normative governance. Otherwise, this process will either remain symbolic or become the incubation phase for new tensions.

For this reason, the governments of Azerbaijan and Armenia must perceive peace not merely as an instrument for geopolitical balancing, but as a strategic rationale for a stable and mutually beneficial future. Only then can the South Caucasus transition from reactive and revanchist politics toward a planned, inclusive, and proactive political model.

Peace in the South Caucasus is neither an inevitable reality nor a distant illusion. It is a rare historical window of opportunity—where political will, regional cooperation, and international guarantees must converge. Time is short, and the responsibility is immense.

References:

- KHAR Center 2025, Tamaşa dövlətçiliyi: Rusiya–Azərbaycan qarşıdurmasının arxa planı https://kharcenter.com/ekspert-serhleri/tamasa-dovletciliyi-rusiya-azerbaycan-qarsidurmasinin-arxa-plani

- Stronski, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2023 https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/02/russias-growing-footprint-in-africas-sahel-region?lang=en

- The Armenian–Turkish Protocols: Diplomacy and Deadlock. Chatham House, 2010.https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Russia%20and%20Eurasia/0310mtgsummary.pdf

- Cornell, Svante E. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Silk Road Paper, 2025. https://www.silkroadstudies.org/publications/silkroad-papers-and-monographs/item/13552-is-central-asia-stable?-conflict-risks-and-drivers-of-instability.html

- International Crisis Group. Improving the Prospects for Peace Between Armenia and Azerbaijan. 2025. https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/caucasus/armenian-azerbaijani-conflict/armenia-and-azerbaijan-getting-peace-agreement-across-finish-line

- Giragosian, Richard. “Why Armenia Needs to Reset Its Foreign Policy.” Open Democracy, 2023 https://www.cmi.no/publications/8911-changing-geopolitics-of-the-south-caucasus-after-the-second-karabakh-war

- Vilsoncenter 2024. “Turkey's Balancing Act: Navigating NATO, BRICS, and Other Global Partnerships https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/turkeys-balancing-act-navigating-nato-brics-and-other-global-partnerships

- TRT World. “Turkey says normalization talks with Armenia will continue in coordination with Azerbaijan.” 2022. https://trt.global/world/article/17196020

- Eurasianet. “Armenia Signals Possible Withdrawal from CSTO.” Eurasianet, February 2024. https://eurasianet.org/armenian-pm-insists-country-has-irrevocably-broken-with-the-russia-led-csto

- EUMA 2024.https://www.eeas.europa.eu/euma/euma-contracts-2024-2025_en?s=410283

- CivilNet. “Pashinyan Reaffirms Recognition of Azerbaijan’s Territorial Integrity.” CivilNet, April 2024. https://civilnet.am

- Narine Chukhuran, Narek Minasyan, Viktorya Muradyan. Armenia’s Shift from Russian, CMF 2024.https://www.gmfus.org/news/shift-away-russia

- Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2024: Azerbaijan and Armenia. https://freedomhouse.org/country/azerbaijan/freedom-world/2024 , https://freedomhouse.org/country/armenia/freedom-world/2024

- International IDEA. Global State of Democracy Report 2023. https://www.idea.int/gsod/2023/

- Giragosian, Richard. "Armenia's Path to Peace: Political Risks and Strategic Necessity." European Council on Foreign Relations, 2023.https://ecfr.eu/profile/richard-giragosian/

- International Crisis Group (ICG). Improving the Prospects for Peace Between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Report 2020 https://www.crisisgroup.org/europe-central-asia/caucasus/nagorno-karabakh-conflict-europe-central-asia-azerbaijan-armenia

- Kucera, Joshua. “Russia’s Waning Influence in the South Caucasus.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Avgust 2024. https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-azerbaijan-karabakh-caucasus-trade-politics/33085516.html