This research analyzes the historical, institutional, ideological, and international foundations of Turkmenistan's authoritarian regime, which took shape after 1991. The study demonstrates that Turkmenistan represents the most closed and rigid authoritarian regime in the post-Soviet space. The regime rests on three primary pillars: a personality cult, an empowered presidential institution, and a repressive security apparatus.

The “neosultanist” model established during the rule of Saparmurat Niyazov has been continued by his successors, Gurbanguly and Serdar Berdimuhamedov, with the leader cult reinforced through the mythology of the Ruhnama and the title Arkadag ("Protector").

INTRODUCTION

In contemporary political systems analysis, the institutional structures, ideological foundations, and role of the international environment are critical elements in understanding authoritarian regimes. These components offer a robust framework for analyzing the durability of authoritarian rule, its potential for transformation, and its interactions with external actors (Matveeva, 2009). The variation in forms of authoritarianism observed across the post-Soviet space calls for a region-specific inquiry.

In this context, Turkmenistan stands out as a unique case. Unlike other Central Asian republics that undertook limited reforms or developed hybrid governance models after the dissolution of the USSR, Turkmenistan has maintained a fully closed, personality-driven, and strictly centralized political system (Heathershaw, 2011). Beginning with the rule of Saparmurat Niyazov, the establishment of a “founding leader cult,” the consolidation of state institutions around the presidency, and the continuation of this system under Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov collectively characterize Turkmenistan as a classic example of a “neosultanist” authoritarian regime (Cummings, 2010a).

At the ideological level, Turkmen authoritarianism is built on national identity, loyalty to the state, and the sanctified image of the leader. The Ruhnama, a quasi-religious and ideological text authored by Niyazov, has played a central role in ideologically homogenizing society, with ideological control imposed across all domains—from education to media discourse (Schatz, 2006).

On the international stage, Turkmenistan has declared itself “neutral,” pursuing balanced yet isolationist relations with global and regional powers. This strategy allows the regime to shield itself from external pressure while selectively engaging in cooperation based on its geopolitical interests, particularly in energy. With a closed information space, a repressive security sector, and a non-transparent governance model, Turkmenistan remains one of the rare states preserving a hardline form of authoritarianism (OSCE/ODIHR, 2022a).

This study seeks to explain how such a rigid form of authoritarianism has been sustained in the post-Soviet space by analyzing the institutional architecture, ideological construction, and international positioning of the Turkmen regime.

METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

This research adopts a qualitative approach and aims to analyze various aspects of Turkmenistan’s political regime, including its historical evolution, institutional makeup, ideological components, and international relations.

The primary sources used in this study include academic literature, reports from international organizations (e.g., Freedom House, Human Rights Watch, OSCE/ODIHR), and expert analyses.

The theoretical basis of the study draws on existing academic approaches to authoritarianism (Levitsky & Way, Cummings, Schatz, among others) and seeks to position Turkmenistan within these conceptual frameworks.

The objective is to understand how the regime was built, what foundations sustain it, and under what conditions it might change.

HISTORICAL–CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND

Understanding Turkmenistan's current political architecture requires examining the legacy of the Soviet system and the dynamics of the post-Soviet transition. The centralized and hierarchical governance model of the USSR—top-down control, the nomenklatura system, and the prohibition of political pluralism—had a lasting impact on Turkmenistan’s state-building process. During the Soviet era, the Turkmen Communist Party operated under the direct authority of Moscow, limiting the autonomy of national elites and concentrating power around the party leadership (Horák, 2016a).

This patrimonial form of governance, inherited from the Soviet period, was retained in the new political configuration and reproduced under different labels. Rather than transitioning to pluralism, Turkmenistan witnessed the centralization of personal power and the formation of a leader cult (Luong, 2002).

In 1999, Saparmurat Niyazov was declared “President for Life” with the title “eternal leader of the nation,” further solidifying the institutional basis of authoritarianism (Horák, 2016b). His leadership exemplified a classic patrimonial model, where state structures were built around personal loyalty (Kuru, 2014).

Niyazov’s book Ruhnama became the centerpiece of state ideology. It was not only a political manifesto but also permeated education, religion, and all aspects of public life, adding a symbolic and totalitarian dimension to state control. Ruhnama was used as a school textbook, included in university entrance exams, and even part of driver’s license tests (Khalid, 2007a). This process centralized both state and societal identity around the symbolic image of the leader.

Following Niyazov’s death in 2006, his successor Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov introduced certain technocratic reforms, but the core features of the political system remained unchanged—authoritarian structures, the continuation of the leader cult, and ideological uniformity (Freedom House, 2024a). This demonstrates that the regime's foundations are not dependent on one individual alone but are entrenched in structural and ideological elements.

INSTITUTIONAL MECHANISMS

Turkmenistan’s political regime is based on a classic hyper-presidential model. The president stands at the center of both the executive and political systems and serves as the ultimate authority in all major decisions. Since 1992, constitutional reforms have expanded presidential powers, elevating the president above the legislature and judiciary and establishing him as a super-institution.

Not only is there a strong presidential system, but deliberate weakening of other institutions is also evident—this is one of the main mechanisms of authoritarian persistence (Cummings, 2010b).

The executive branch is fully subordinated to the president. The Cabinet of Ministers is composed of individuals appointed by the president, with no real parliamentary oversight. The Turkmen parliament—Mejlis—formally exists, but its real function is symbolic. It is effectively excluded from legislative initiative and the decision-making process. Since its members are selected or approved by the president, the parliament serves primarily to create a façade of legitimacy.

One of the regime's core pillars is its security apparatus. The Ministry of National Security (Milli Howpsuzlyk Ministrligi), the successor of the Soviet KGB, is responsible for monitoring political opposition, persecuting dissidents, censoring the media, and ensuring public control. According to human rights organizations, critics of the regime are subjected to physical abuse, arbitrary detention, and prolonged isolation without trial (Human Rights Watch, 2023).

Unlike the “competitive authoritarianism” model described by Levitsky and Way, Turkmenistan fits more closely with the “hegemonic authoritarianism” category (Levitsky & Way, 2010). In such systems, formal institutions—parliaments, elections, courts—exist, but the regime’s dominance prevents any genuine competition. Political opponents are systematically eliminated, and elections become predetermined formalities. In Turkmenistan, there are no credible opposition candidates, balanced media coverage, or objective election monitoring, all of which deepen the regime’s totalitarian/authoritarian character (OSCE/ODIHR, 2022b).

Moreover, the judiciary is completely subordinated to political power. Judges are appointed and dismissed by the president, sometimes arbitrarily. Court decisions have no real influence on political processes, as legal institutions are primarily tasked with protecting the regime’s interests.

In summary, Turkmenistan’s institutional system—an empowered presidency, a symbolic and weak parliament, politically driven security agencies, and a non-independent judiciary—constitutes a centralized and authoritarian governance structure that ensures regime durability.

Ideology and Cultural Control

One of the key mechanisms ensuring the persistence of authoritarian regimes is ideological domination and cultural control. In the case of Turkmenistan, these processes have been systematized through the Ruhnama, a book authored by Saparmurat Niyazov, which has permeated all spheres of state life. This work transcended its role as a literary or historical text and became the symbol of state ideology. As a unique ideological instrument, it reinforced the leader cult and operated as an extensive mechanism of social control.

The media and information resources are entirely under state control. The operation of independent media outlets is practically impossible in the country, and any attempt at free journalism is met with severe censorship. Access to foreign information sources is restricted, and internet connectivity is heavily monitored. The use of VPNs and other anonymization technologies is criminalized, which sharply limits the flow of information among citizens (Reporters Without Borders, 2023). This situation creates a state of information asymmetry, allowing the regime to maintain ideological influence and control over public opinion.

In the religious sphere, state control is also strong. Alongside the Ruhnama ideology, independent religious activities and organizations are suppressed, and only state-approved religious institutions are permitted to function (Khalid, 2007b). This serves the dual purpose of preserving social stability and preventing the emergence of potential religious opposition.

Thus, ideological and cultural control mechanisms function as key pillars that provide legitimacy to Turkmenistan's authoritarian regime. Through the leader cult and cultural domination, a significant portion of society is compelled to accept the state’s political line, while the dissemination of alternative ideas is strictly obstructed.

The Berdymukhamedov Era: Authoritarian Continuity and Neo-Monarchic Consolidation

Following the death of Saparmurat Niyazov in 2006, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov came to power and initially adopted a rhetoric of reform. However, this rhetoric ultimately amounted to symbolic and demonstrative gestures. Some of the more extreme visual elements of Niyazov’s personality cult—such as Ruhnama-centered practices and golden statues—were removed, but a new personal cult structure was built in their place. Presented as “Arkadag” (“Protector Father”), Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov became the new ideological center of the state, ensuring the symbolic renewal of authoritarianism. This was not just a change in symbols but an adaptation of the authoritarian state model—forms changed, but the content became even more centralized and normalized (Koch, 2013).

In this new phase, the Berdymukhamedov regime introduced certain elements of technocratic governance: digitalization initiatives, infrastructure projects, and international exhibitions showcasing a “modernizing” image of Turkmenistan. However, these were merely superficial modernizations that did not affect the core of political institutions. The entire power vertical remained tied to the president’s will, and law enforcement agencies continued to suppress even the most minimal expressions of civil society (Freedom House, 2024b).

In 2022, the presidency was transferred to Berdymukhamedov’s son, Serdar, openly revealing the neo-monarchic character of Turkmenistan’s regime. This was one of the clearest manifestations of dynastic authoritarianism in the post-Soviet space. The model was based not on institutional legitimacy, but on familial and generational succession, continuing the use of the leader’s personal authority as the primary political mechanism. Serdar Berdymukhamedov’s presidency, for now, remains largely ceremonial, while real power appears to remain in the hands of his father, who retains the title of Arkadag (Bohr, 2022).

It is worth noting that this model is not unique to Turkmenistan but aligns with a broader trend evident in authoritarian regimes across Central Asia and the Caucasus, including Azerbaijan: the cult of personality, superficial technocratic modernization, and intra-family transfer of power. Turkmenistan stands out as the most radical embodiment of this structure, characterized by both deep political passivity and enduring repression.

International Context

Turkmenistan’s foreign policy is shaped by its “permanent neutrality” status, which provides it with unique advantages in international relations. Recognized by the United Nations in 1995, this status keeps Turkmenistan out of military alliances and great power rivalries, serving as a means of protecting national sovereignty (Anceschi, 2020a). At the same time, this policy allows the regime to evade international scrutiny and criticism, granting it greater freedom in domestic affairs.

Strategic relations with major authoritarian states like Russia and China underpin Turkmenistan’s economic and political stability. Long-term cooperation with Russia exists in both military and energy sectors, though Russia’s influence is primarily political. In contrast, China has recently become the dominant economic partner, mainly as the primary buyer of Turkmen gas—thereby increasing its geopolitical leverage in the region (Peyrouse, 2022).

China’s deepening economic relations with Turkmenistan have provided the regime with significant financial resources and a degree of economic independence. Through the “Belt and Road” Initiative, cooperation with China has expanded to include investment in energy infrastructure and the transportation sector (Anceschi, 2020b). This has enabled Turkmenistan to present itself as a stable and reliable partner in the international arena.

Nonetheless, in the international context, Turkmenistan’s policy of permanent neutrality and its selective financial and political alliances with foreign states function as crucial factors supporting the persistence of its internal authoritarian regime. These factors strengthen Turkmenistan’s geopolitical standing in the region and enhance its competitiveness at the global level.

Turkmenistan and Models of Authoritarianism in the Region

Although the authoritarian regimes in Central Asia share structural similarities, they follow different developmental trajectories. In this sense, Turkmenistan stands apart by having formed the most closed, personality-centered, and ideologically monolithic political system. Unlike other post-Soviet republics such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan has neither attempted simulated political liberalization nor pursued substantial institutional reforms.

For example, since 2019 Kazakhstan has undertaken a formal leadership transition, introduced minor liberalizations in party legislation, and implemented reforms aimed at improving its international image, following a path of “authoritarian modernization.” Uzbekistan under Shavkat Mirziyoyev has initiated certain economic reforms, introduced technocratic changes, and allowed limited media openness (BTI, 2024). Turkmenistan, by contrast, has created neither a climate for economic diversification nor conditions conducive to political competition, making it the most consistent example of neo-sultanist authoritarianism (Cummings, 2010).

These differences are also reflected in foreign policy approaches. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan pursue multi-vector diplomacy and are more open to cooperation with Western institutions. Turkmenistan, by contrast, isolates itself from such platforms through its “permanent neutrality” status and prefers bilateral relations with China and Russia characterized by authoritarian compatibility.

China and Russia: Two Distinct Models of Authoritarian Influence

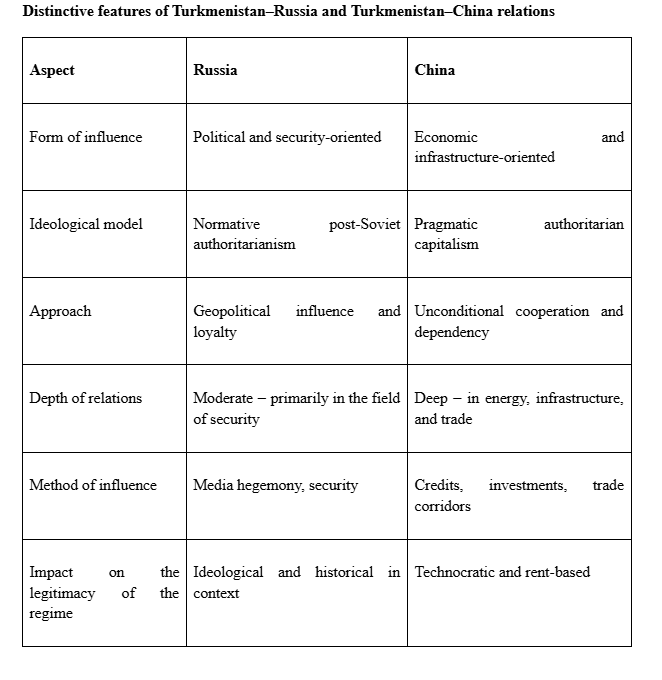

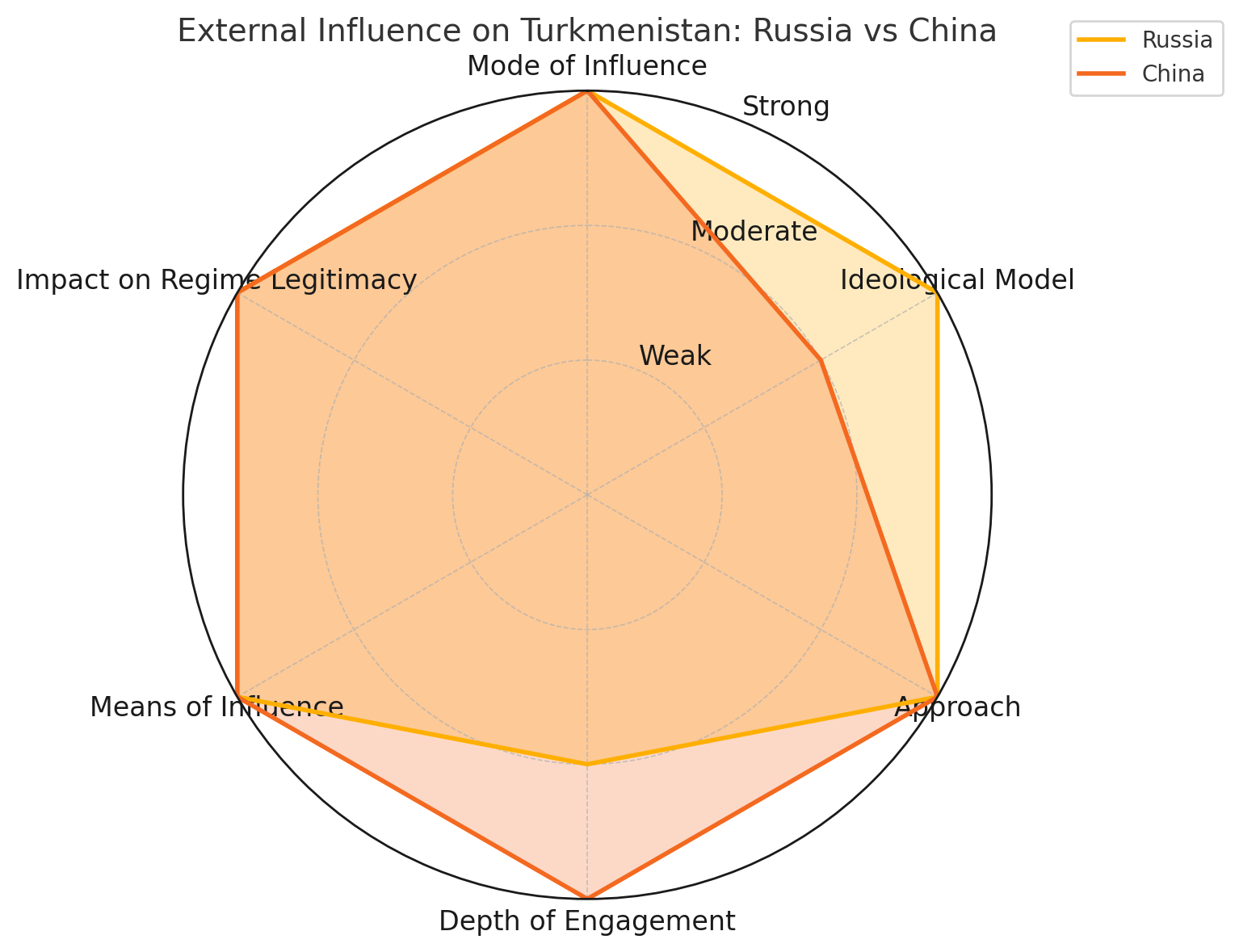

Although China and Russia are both dominant actors in Turkmenistan’s foreign relations, their strategies of influence differ significantly in nature and purpose.

- Russia: Normative-Political and Security-Oriented Influence

The Russian Federation exercises influence in Central Asia mainly through political loyalty, security cooperation, dissemination of Russian media, and promotion of the Russian language. While Turkmenistan is not formally a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) or the Eurasian Economic Union, bilateral security ties with Russia exist, and Moscow views Turkmenistan as a regional actor that should remain “under supervision” in the post-Soviet integration discourse (Anceschi, 2020c).

Additionally, for the Turkmen political elite, the Russian model represents a familiar and inherited mode of governance, which reinforces adaptation to Russian norms and helps preserve the authoritarian status quo.

- China: Economic Dominance and a Non-Interventionist Approach

China’s primary influence is rooted in economic dependency. Over 80% of Turkmen gas exports are directed to China, creating a structural dependency in the energy sector (Farkhod Aminjonov, 2018). The Chinese government has invested heavily in Turkmenistan’s infrastructure, transportation corridors, and energy logistics systems—establishing a deep presence under the Belt and Road Initiative.

China’s principle of non-intervention in domestic affairs makes it an ideal strategic partner for Turkmenistan. This is perceived as a model of “unconditional support,” enabling authoritarian regimes to evade international pressure.

This graphic compares the influence of Russia and China on Turkmenistan across six main aspects. Russia and China represent two key pillars sustaining Turkmenistan’s authoritarian durability in the international system. However, their modes of influence are complementary rather than substitutive. Russia acts more as a provider of ideological and symbolic legitimacy, while China plays the role of ensuring material and technocratic stability. Turkmenistan, in turn, pursues a strategy of strategic balancing between these two models, seeking to extract maximum concessions from both sides — a strategy that simultaneously shields the regime from external pressure and sustains the continuity of domestic authoritarian structures.

Society and the Potential for Social Resistance

Due to the high level of political repression and information control in Turkmenistan, open opposition and organized civic activism are virtually non-existent. However, this does not imply that society is entirely passive or homogenous. On the contrary, in repressive regimes, there often exist forms of “silent dissent” and hidden resistance, with political participation expressed through informal channels.

In a context where the regime’s sources of legitimacy rely mainly on symbolic authority, fear, and a system of rewards, passive resistance at the individual level — including non-compliance, disengagement, technical disobedience, and everyday indifference — is widespread. These behaviors can be understood through James Scott’s conceptual framework as “hidden transcripts” or “simulated administrative loyalty” — whereby citizens demonstrate loyalty in the public sphere but form alternative or critical views in private (Bertelsmann Transformation Index, 2024).

Foreign Diaspora and Informational Resistance

The boundaries of authoritarian control have become more permeable, especially in the context of rapid technological advancement and transnational migration flows. In this regard, the Turkmen diaspora abroad — particularly in countries such as Norway, Turkey, the United States, and European states — has emerged as a key actor in informational resistance. Exile media platforms like Chronicles of Turkmenistan (Turkmen.news), Radio Azatlyk (the Turkmen service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty), and various social media accounts partially challenge the regime’s monopoly on information. These channels enable the circulation of alternative narratives within Turkmenistan and offer symbolic counter-discourses to the regime's dominance.

Although transnational information circulation is often selective, fragmented, and decentralized, it enables the emergence of forms of epistemic resistance among segments of the population. This resistance is not just about accessing information — it also involves questioning the regime’s ideological frameworks and proposing alternative models of reality. Modern political theorists such as David K. Runciman and Jason Stanley emphasize that authoritarian regimes maintain control over information not only through censorship and persecution but also via epistemic hegemony — control over how information is interpreted and understood (Stanley, How Fascism Works, 2018).

In this context, foreign sources of information — especially media outlets founded by diaspora activists — play both an informational and symbolic role in resistance. In Turkmenistan’s closed information environment, these channels represent more than just “leaks”; they serve as platforms for preserving collective memory, amplifying the voices of victims of repression, and imagining alternative futures (Morozov, The Net Delusion, 2011; Pearce & Kendzior, 2012).

This flow of information does more than challenge the regime’s discourse; it enables transnational discursive interventions against the surveillance and control techniques maintained by the regime through digital means. In this way, diaspora-based media structures — no matter how decentralized or vulnerable — expand the possibilities of epistemic freedom and undermine authoritarian hegemony in the local context.

Socioeconomic Apathy and Exit Strategies from the System

Mass labor migration, which has resulted from the regime’s socioeconomic policies, can be interpreted as an indirect manifestation of political discontent. The “authoritarian bargain” offered by the state — political silence in exchange for stable welfare and social guarantees — has become increasingly unreliable in the context of economic instability. Thus, migration becomes not only an economic choice but also a form of exit from the system and a passive method of resistance against the regime.

Youth and Technological Adaptation

Despite the regime’s implementation of strict information censorship, digital literacy and access to hidden online networks among the youth are on the rise. Using VPN technologies, encrypted messaging apps, and social media platforms, young people seek to bypass official discourse and access unofficial sources of information. In the long term, this process may erode the ideological hegemony of the state.

Weakness of Potential Social Bases

Nevertheless, the necessary social foundations for systematic and institutional resistance — such as independent intellectual environments, legal defense institutions, and organized civil society — are absent in Turkmenistan. High levels of mutual distrust within society, the widespread use of informants, and an atmosphere of fear prevent collective mobilization. This deepens what Mancur Olson (1971) referred to as the collective action dilemma.

Conclusion

Turkmenistan’s authoritarianism has preserved a unique, closed, and highly centralized governance model in the modern political arena. This model rests on the cult of personal rule, rigid centralization of institutional mechanisms, and extensive ideological control. The ideological discourse built around Ruhnama, total control over the national information space, and the functionality of a repressive apparatus serve as guarantors of internal regime stability. On the international front, the strategy rests on the “permanent neutrality” status and wide-ranging, multifaceted economic-political ties with key strategic partners like Russia and China.

However, this political model faces serious structural and contextual limitations to its long-term sustainability. The economy’s heavy dependence on the energy sector — especially given the volatility of global energy markets and the rapid development of environmentally friendly alternatives — puts Turkmenistan’s economic security at risk. The regime’s isolation in the technological and informational domains increases the potential for social dissatisfaction among the younger generation and weakens the state’s support base. Moreover, factionalism and internal competition within the ruling elite may pose significant threats to political stability.

Looking ahead, Turkmenistan is likely to remain one of the most closed and rigid political systems in the region. However, fundamental shifts in the global energy market, technological revolutions, and rising socio-political demands from society may force the regime to adapt and undertake institutional reforms.

References:

- Matveeva, Anna. 2013."Legitimising Central Asian authoritarianism: Political manipulation and symbolic power." In Symbolism and Power in Central Asia. Routledge, 2013.

- Heathershaw, John, and Edmund Herzig. 2013. The transformation of Tajikistan. Routledge: The Sources of Statehood, 2013.

- Cummings, S. N. 2012a. Understanding Central Asia: Politics and Contested Transformations.Routledge.https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203403143/understanding-central-asia-sally-cummings

- Schatz, E. 2006. Access by Accident: Legitimacy Claims and Democracy Promotion in Authoritarian Central Asia. International Political Science Review, 27(3), 263–284.

- OSCE/ODIHR. (2022)a. Election Assessment Mission Report: Turkmenistan Presidential Election.https://www.osce.org/odihr/513568

- Horák, S. (2016)a. Legitimacy Building in Turkmenistan: Beyond Personality Cults. Central Asian Survey, 33(4), 449–462. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345619941_Personality_Cults_and_Nation-Building_in_Turkmenistan_1_2

- Luong, P. J. (2002). Institutional Change and Political Continuity in Post-Soviet Central Asia: Power, Perceptions, and Pacts. Cambridge University Press.https://assets.cambridge.org/97805218/01096/sample/9780521801096ws.pdf Amazon+2assets.cambridge.org+2AbeBooks+2

- Kuru, A. T. 2014. Authoritarianism and Democracy in Muslim Countries: Rentier States and Regional Diffusion. Political Science Quarterly, 117(4), 595–608.

- Khalid, A. 2007a. Islam after Communism: Religion and Politics in Central Asia. University of California Press.https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520282155/islam-after-communism

- Freedom House. (2024)a. Nations in Transit 2024: Turkmenistan. https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkmenistan/freedom-world/2024

- Horák, S. (2016)b. Legitimacy Building in Turkmenistan: Beyond Personality Cults. Central Asian Survey, 33(4), 449–462. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345619941_Personality_Cults_and_Nation-Building_in_Turkmenistan_1_2

- Cummings, S. N. 2012b. Understanding Central Asia: Politics and Contested Transformations.Routledge.https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203403143/understanding-central-asia-sally-cummings

- Human Rights Watch. (2023). World Report 2023: Turkmenistan.https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/11/21/turkmenistan-journalist-prevented-travelling-abroad

- Levitsky, S., & Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/competitive-authoritarianism/20A51BE2EBAB59B8AAEFD91B8FA3C9D6

- OSCE/ODIHR. (2022)b. Election Assessment Mission Report: Turkmenistan Presidential Election. https://www.osce.org/odihr/513568

- Horák, S. (2016)c. Legitimacy Building in Turkmenistan: Beyond Personality Cults. Central Asian Survey, 33(4), 449–462.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345619941_Personality_Cults_and_Nation-Building_in_Turkmenistan_1_2

- Reporters Without Borders. (2023). 2023 World Press Freedom Index: Turkmenistan. https://rsf.org/en/turkmenistan

- Khalid, A. (2007)b. Islam after Communism: Religion and Politics in Central Asia. University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520282155/islam-after-communism

- Koch, N. (2013). The “personality cult” problematic: Personalism and mosques memorializing the “father of the nation” in Turkmenistan and the UAE. Europe-Asia Studies, 65(6), 1089–1108. https://nataliekoch.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Koch_Mosques_web.pdf

- Freedom House. (2024)b. Nations in Transit 2024: Turkmenistan. https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkmenistan/freedom-world/2024

- Anceschi, L. (2020)a. Turkmenistan’s Foreign Policy: Neutrality, Regionalism, and Strategic Balancing. Routledge. https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781134051564_A24928741/preview-9781134051564_A24928741.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Farkhod Aminjonov. 2018. Statecraft in the Steppes: Central Asia’s Relations with China https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10670564.2022.2136937#abstract

- Anceschi, L. (2020)b. Turkmenistan’s Foreign Policy: Positive Neutrality and the consolidation of the Turkmen regime. Routledge .https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781134051564_A24928741/preview-9781134051564_A24928741.pdf

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI). (2024). Country Report: Turkmenistan. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/TKM

- Turkmen.News. https://www.turkmen.news/

- Radio Azatlyk – Azadlıq Radiosunun Türkmən Xidməti. https://www.azathabar.com/

- Jason Stanley, How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them (New York: Random House,2018).https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/566247/how-fascism-works-by-jason-stanley/

28. Olson, M. (1971). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press. https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674537514