Relations between Azerbaijan and Western countries are entering a complex phase. On the one hand, the abolition of independent media outlets, the growing number of arrests targeting journalists and human rights defenders, and pressure campaigns against critical diaspora groups have reached their peak domestically. On the other hand, Azerbaijan’s rapprochement with the European Union has become increasingly visible. Discussions on security, energy, and transportation issues are deepening; bilateral relations are being reshaped, and new models of cooperation are expanding.

Introduction

For many years, Western countries’ relations with the Azerbaijani government have been grounded primarily in concrete interests such as energy security and regional stability. However, during earlier periods, this type of close cooperation used to be at least accompanied by parallel discussions on human rights issues. Today, strong reactions concerning political prisoners or protests regarding the dismantling of civil society no longer appear in the daily agenda.

This situation cannot be explained solely by changes in Western priorities. In the emerging global geopolitical configuration — where energy and transport routes are being redefined, and projects such as the Middle Corridor and the Black Sea strategy gain prominence — Azerbaijan has become a strategic hub in the region. Baku uses this geo-economic significance to expand its political leverage and to legitimize its authoritarian governance model internationally. As a result, the new cooperation between the parties is characterized not as a “values-based partnership,” but as “interest-based relations.”

This article examines how Azerbaijan–EU relations have evolved in the context of repression, the geopolitical and normative consequences of this rapprochement, and the implications of increasing regional authoritarian consolidation.

The Cross-Border Phase of Repression

The repressive wave that began two years ago — which resulted in the arrest of employees of “Abzas Media,” “Toplum TV,” “Meydan TV,” as well as several politicians and activists — has taken on a cross-border dimension, reaching Azerbaijani bloggers and political activists abroad. In recent days, the Prosecutor General’s Office of Azerbaijan has hypocritically “invited” these individuals to give statements, despite the fact that they would be immediately detained and taken to a detention facility should they set foot on Azerbaijani soil.

From the West, however, neither official protests nor even traditional statements of concern regarding the dramatic state of civil rights and liberties in Azerbaijan have been heard. In reality, Western countries have always taken a pragmatic stance in their relations with the Azerbaijani authorities, with cooperation centred on energy and security issues. Nevertheless, they also used to voice objections to politically motivated persecution in Azerbaijan — and this sometimes caused friction with the regime in Baku. It now appears that, influenced by the new global geopolitical realities, Western actors have agreed to structure relations with Azerbaijan precisely as the autocracy desires — on its own terms. (It cannot be ruled out that political prisoner issues are raised behind closed doors, though this does not change the overall picture.)

A Turning Year in EU–Azerbaijan Relations

After the Second Karabakh War, the key sources of tension between Azerbaijan and Europe (institutions and individual states) can be grouped under three headings:

1. Problems with the European Union: Baku reacted sharply and disproportionately to the EU’s decision to deploy an observation mission in Armenia and to allow monitoring activities along the Armenian–Azerbaijani border. The Azerbaijani government accused the mission of espionage and even preparing for war. EU criticism — particularly from the previous EU leadership and the European Parliament — regarding human rights conditions in Azerbaijan had also sparked harsh responses from Baku.

2. Bilateral tensions with France and the Netherlands: Azerbaijan considered the positions of both countries “one-sided, biased, and pro-Armenian” in the post-conflict period. France’s intensified ties with Armenia — extending into the military sphere and aiming for a stronger presence there — were particularly criticized.

3. The Council of Europe (PACE) crisis: After the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe refused to approve the credentials of the Azerbaijani delegation, Azerbaijan suspended its participation in PACE. President Aliyev even announced that Azerbaijan would no longer recognize the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. (Ilham Aliyev, 9 April 2025.)

It can now be said that the first two problems have largely been overcome. The paraphing of a peace treaty between Azerbaijan and Armenia in Washington in August, as well as the agreement on the TRIPP transport route that resolved long-standing disputes over transit through Armenia, have been among the factors positively affecting EU–Azerbaijan relations. Yet the main driver is the political will of the parties themselves.

A major boost came with the April visit to Baku by Kaya Kallas — the EU’s new High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission (President.az, 25 April 2025). This was followed by the 6th Azerbaijan–EU Security Dialogue meeting in Brussels in May; the 3rd Azerbaijan–EU Energy Dialogue in Brussels in June; and the 2nd high-level Transport Dialogue in Brussels in October. In September, the EU Commissioner for Enlargement, Marta Kos, also visited Azerbaijan and toured reconstruction efforts in liberated Aghdam, praising the work underway (AZERTAC, Sept 2025).

The priorities of this partnership become clear from the dialogue topics: security, energy, and transport.

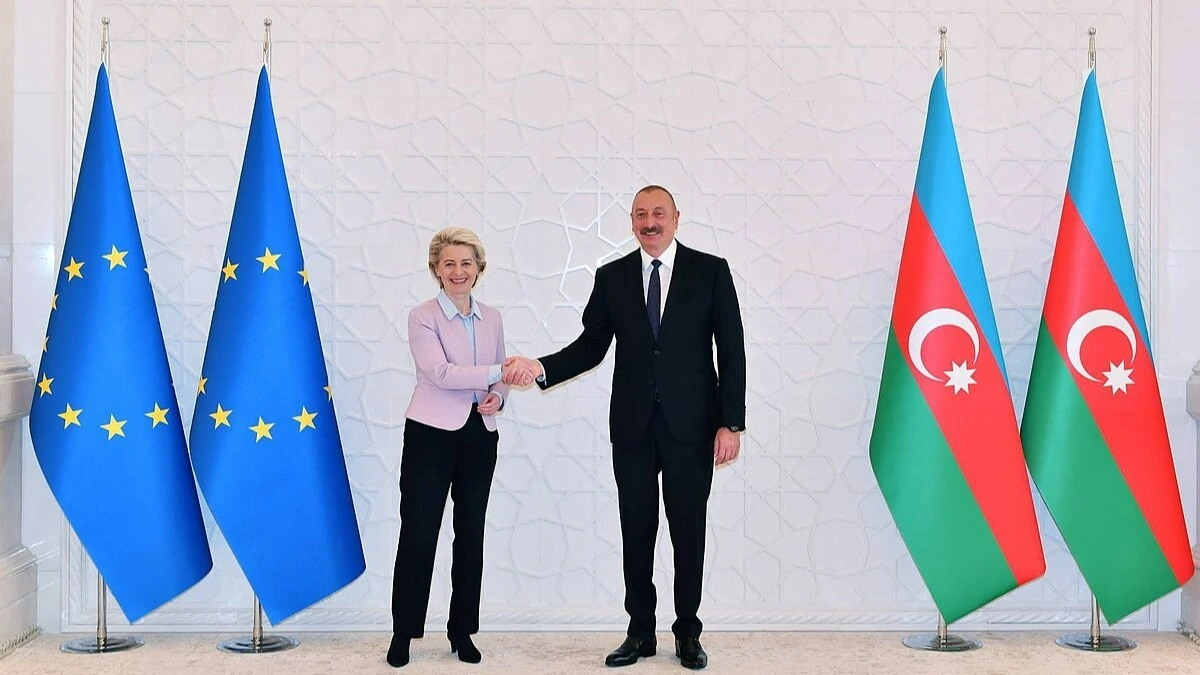

After the start of the war in Ukraine, the EU adopted a strategic decision to end its dependence on Russian energy and began searching for alternative sources. One of these sources is Azerbaijan and Central Asia. During the July 2022 visit of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to Baku — just five months into the war — a Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership in the energy sphere was signed (President.az, 2022). Azerbaijan pledged to increase the volume of natural gas supplied to Europe. The West now views Azerbaijan and the Central Asian states as a single geo-economic space. To access the region’s energy and mineral resources, the EU is raising its relations with these former Soviet republics to a truly strategic level. The only viable route for transporting Central Asian resources to Europe is through Azerbaijan — via the Middle Corridor.

The new EU Ambassador to Azerbaijan, Mariana Kuyundzic — appointed after the term of Peter Michalko, whose tenure had caused discontent in Baku — highlighted energy and transport as priority areas during her meeting with President Aliyev and expressed support for regional connectivity projects (Qafqazinfo, 2024; President.az, October 2025).

The fact that democracy and human rights issues are not only non-priorities for the EU but have been entirely sidelined satisfies regional autocracies and creates a favourable environment for cooperation. These values are now neither heard in rhetoric nor seen in written documents.

This is not entirely new. For example, the Partnership Priorities adopted on 28 September 2018 — based on the recommendation of the EU–Azerbaijan Cooperation Council — included the following areas of cooperation:

- Strengthening institutions and good governance;

- Economic development and market opportunities;

- Connectivity, energy efficiency, environment, and climate action;

- Mobility and people-to-people contacts (mfa.gov.az).

A significant new development is that Baku and Brussels have agreed to start negotiations on updated Partnership Priorities and to resume negotiations on a comprehensive Agreement (APA, November 2025).

The “Forgotten” Strategic Partnership Agreement

The foundation of relations between Azerbaijan and the EU is the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement signed in 1996 and in force since 1999. This document — covering all sectors except defence — defined the legal basis and format of cooperation and was originally signed for ten years, after which its application has been automatically extended annually in the absence of a new agreement.

In 2010, negotiations began on an Association Agreement. However, Azerbaijan refused to sign a document that had caused geopolitical upheaval in the post-Soviet region and provoked a harsh reaction from Russia. Instead, Baku proposed negotiating a Strategic Partnership Agreement (APA, 2014). Talks on this agreement started in 2017. Negotiations were held in three blocks: political and security issues; trade and investment; and sectoral issues.

For the past five years, the parties have been unable to finalize the draft agreement. Head of the Azerbaijani delegation Mahmud Mammadquliyev stated in 2019 that part of the document was ready, but that discussions on trade were ongoing (Report, 2019).

The most recent round of talks took place in December 2022, with no public information about outcomes. A pause followed.

It is known that Azerbaijan’s main objection concerned WTO accession. Baku does not want to align itself fully with WTO norms, even though it filed its own application for membership in 1997. It is possible that in the new geopolitical environment — shaped by Trump’s re-election, the rise of protectionism, and the fading relevance of multilateral trade mechanisms — the EU may no longer insist on this issue.

The EU’s Black Sea Strategy

In May, the European Union announced its new Black Sea Strategy. Entitled “A New Strategy for a Safe, Prosperous, and Resilient Black Sea Region,” the document aims to strengthen the EU’s geopolitical role in the context of Russia’s war against Ukraine by connecting Europe more effectively with the South Caucasus, Central Asia, and other regions.

The EU identifies three main pillars for cooperation in the Black Sea region:

- Strengthening security, stability, and resilience;

- Supporting sustainable development and progress;

- Protecting the environment, preparing for climate change, and supporting civil protection.

Nowhere in the document is there mention of supporting democratization or expanding rights and freedoms in the region. It merely states that countries wishing to integrate with the EU will be guided toward alignment with the EU’s common foreign and security policy by strengthening rule of law and accelerating reforms (Enlargement.ec.europa.eu, May 2025). This applies to EU candidate states — not to Azerbaijan or Central Asia.

Normalization with France: Farewell, New Caledonia…

On 16 October, President Ilham Aliyev effectively held an “informal Europe Day” in Baku. On this day, he received the credentials of the new ambassadors of France, the Netherlands, and the European Union and made important statements.

Aliyev told the French ambassador that his meeting with President Macron in Copenhagen had resolved misunderstandings between the two countries and that a “new phase” in bilateral relations had begun (Report, October 2025). The meeting took place on 2 October during the 7th European Political Community Summit. Azerbaijani and French official photographs from that meeting showed the two leaders smiling warmly (President.az, October 2025).

Signs of this “new phase” are already visible. The activities of the Baku Initiative Group — established by the Azerbaijani government to fight “French colonialism” — and the Azerbaijani parliament’s friendship group in support of the Corsican people, as well as Azerbaijani media reports on the “dire situation” in New Caledonia, Mayotte, Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, and other overseas territories, have disappeared. This confirms that the crisis in bilateral relations has ended.

The Copenhagen backstage diplomacy also played a key role in normalization with the Netherlands. During the ambassador’s credential ceremony, Aliyev emphasized that his meeting with Dutch Prime Minister Dick Schoof had resulted in agreements to strengthen cooperation in several areas (President.az, October 2025). Shortly afterward, Azerbaijan’s deputy foreign minister visited the Netherlands (Report, October 2025). On the same day, the head of the Department for Foreign Policy Affairs in the Presidential Administration, Hikmet Hajiyev, visited Germany and held meetings with the chancellor’s foreign and security policy adviser and the state secretary of the foreign ministry (Report, October 2025).

As of now, there has been no progress regarding relations with the Council of Europe. It is possible that contacts will take place ahead of the January 2026 PACE session. For Azerbaijan to regain its voting rights in PACE, certain domestic softening measures would be required — at minimum, stopping the repression and releasing political prisoners. Whether the regime is willing to take these steps to return to PACE remains to be seen; for now, no definitive assessment can be made.

Conclusion

The current warming in relations between Azerbaijan and Europe extends beyond the classic “democracy vs. energy” dilemma and reflects deeper structural shifts. The European Union and key European states foreground Azerbaijan’s growing geopolitical role as a regional security actor, energy supplier, and transit hub along the Middle Corridor (Kharcenter, Nov 2025). In this environment, human rights and democracy no longer appear as conditions for cooperation. This is visible in the Black Sea Strategy, in dialogue agendas, and in the normalization of ties with Paris and The Hague: values recede; interests define the framework of engagement.

This new configuration yields three major consequences:

First, the reduction of international pressure enables the consolidation of domestic repression. European indifference allows the Azerbaijani government to continue persecuting opposition figures, activists, independent media, and diaspora critics with fewer reputational costs.

Second, relations between Baku and the West shift away from a normative framework toward a realpolitik model. Cooperation now revolves around energy, security, and communications projects; political liberalization, rule of law, and human rights no longer function as terms of engagement. This weakens the EU’s identity as a values-based actor in the post-Soviet region and erodes Europe’s normative advantage in its competition with Russia and China.

Third, the emerging model of cooperation strengthens authoritarian consolidation in the broader region. Central Asian states are pursuing similar patterns with Europe; reduced normative demands and increased cooperation in energy and transport sectors contribute to the formation of an “authoritarian bloc.” Azerbaijan plays a central role in this bloc through its resources, transit potential, and security posture.

This configuration raises a logical question: Is the West abandoning its values and granting geopolitical legitimacy to authoritarian modernization, or is this merely a temporary realpolitik compromise?

The answer depends not only on the future behaviour of Europe’s democratic institutions but also on the prospects of change within Azerbaijan’s domestic political system. For now, the reality highlights a “rapprochement under the shadow of intensified repression” in Baku–Brussels relations. The negative consequences of this process pose serious questions for the democratic future of Azerbaijani society.

References:

1. İlham Əliyev, Aprel 2025. “Avropa Məhkəməsinin qərarlarını tanımayacağıq”. https://toplummedia.tv/siyaset/pilham-eliyev-span-stylecolore74c3cldquoavropa-mehkemesinin-qerarlarini-tanimayacagiqrdquospanp

2. Prezident. Az, 2025. İlham Əliyev Avropa Komissiyasının vitse-prezidenti Kaya Kallası qəbul edib. https://president.az/az/articles/view/68647

3. Azertac, 2025. Azərbaycan dövlətinin həyata keçirdiyi bərpa və yenidənqurma işləri təqdirəlayiqdir. https://azertag.az/xeber/ai_nin_komissari_azerbaycan_dovletinin_heyata_kechirdiyi_berpa_ve_yenidenqurma_isleri_teqdirelayiqdir_video-3751615

4. Prezident. Az, 2022. Azərbaycan ilə Avropa İttifaqı arasında enerji sahəsində Strateji Tərəfdaşlığa dair Anlaşma Memorandumu imzalanıb. https://president.az/az/articles/view/56689

5. Qafqazinfo, 20204. Aİ-nin ofisində müxalifətlə görüş - Nə danışıblar? https://qafqazinfo.az/news/detail/ai-nin-ofisinde-muxalifet-liderleri-ile-gorus-ne-danisiblar-444326

6. Prezident.az, 2025. İlham Əliyev Avropa İttifaqının ölkəmizdəki nümayəndəliyinin yeni təyin olunmuş rəhbərinin etimadnaməsini qəbul edib. https://president.az/az/articles/view/70347

7. MFA. Azərbaycan - Avropa İttifaqı münasibətləri. https://mfa.gov.az/az/category/regional-organisations/relations-between-azerbaijan-and-european-union

8. APA, 2025. Azərbaycan Aİ ilə yeni hərtərəfli Saziş layihəsi üzrə danışıqları bərpa edir. https://apa.az/foreign-policy/azerbaycan-ai-ile-yeni-herterefli-sazis-layihesi-uzre-danisiqlari-berpa-edir-925212

9. APA, 2014. Novruz Məmmədov Azərbaycanın Avropa İttifaqının “Assosiasiya sazişi” imzalanması təklifinə cavab verməməsinin səbəbini açıqlayıb. https://apa.az/xarici-siyaset/xeber_novruz_memmedov_azerbaycanin_avropa_itti_-362243

10. Report, 2019. Nazir müavini: “Azərbaycan və Aİ arasında yeni sazişin bir hissəsi artıq hazırdır”. https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/nazir-muavini-azerbaycan-ve-ai-arasinda-yeni-sazisin-bir-hissesi-artiq-hazirdir

11. Enlargement and Eastern Neighbourhood, 2025. New EU strategy for secure, prosperous and resilient Black Sea region. https://enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/new-eu-strategy-secure-prosperous-and-resilient-black-sea-region-2025-05-28_en?prefLang=ru&etrans=ru

12. Report, 2025. Azərbaycan Prezidenti Fransanın yeni səfirinin etimadnaməsini qəbul edib. https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/azerbaycan-prezidenti-fransanin-yeni-sefirinin-etimadnamesini-qebul-edib

13. President.az, 2025. İlham Əliyevin Kopenhagendə Fransa Prezidenti ilə görüşü olub . https://president.az/az/articles/view/70255

14. President.az, 2025. İlham Əliyev Niderlandın Azərbaycanda yeni təyin olunmuş səfirinin etimadnaməsini qəbul edib. https://president.az/az/articles/view/70345

15. Report, 2025. Azərbaycanla Niderland beynəlxalq və regional məsələləri müzakirə edib. https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/elnur-memmedov-niderland-xin-bascisinin-muavini-ile-gorusub

16. Report, 2025. Hikmət Hacıyev Almaniya kanslerinin müşaviri ilə görüşüb. https://report.az/xarici-siyaset/azerbaycan-ve-almaniya-ikiterefli-ve-regional-meseleler-muzakire-edib

17. Kharcenter, Nov 2025. Authoritarian Alliances Across the Caspian. https://kharcenter.com/en/expert-commentaries/authoritarian-alliances-across-the-caspian