Introduction

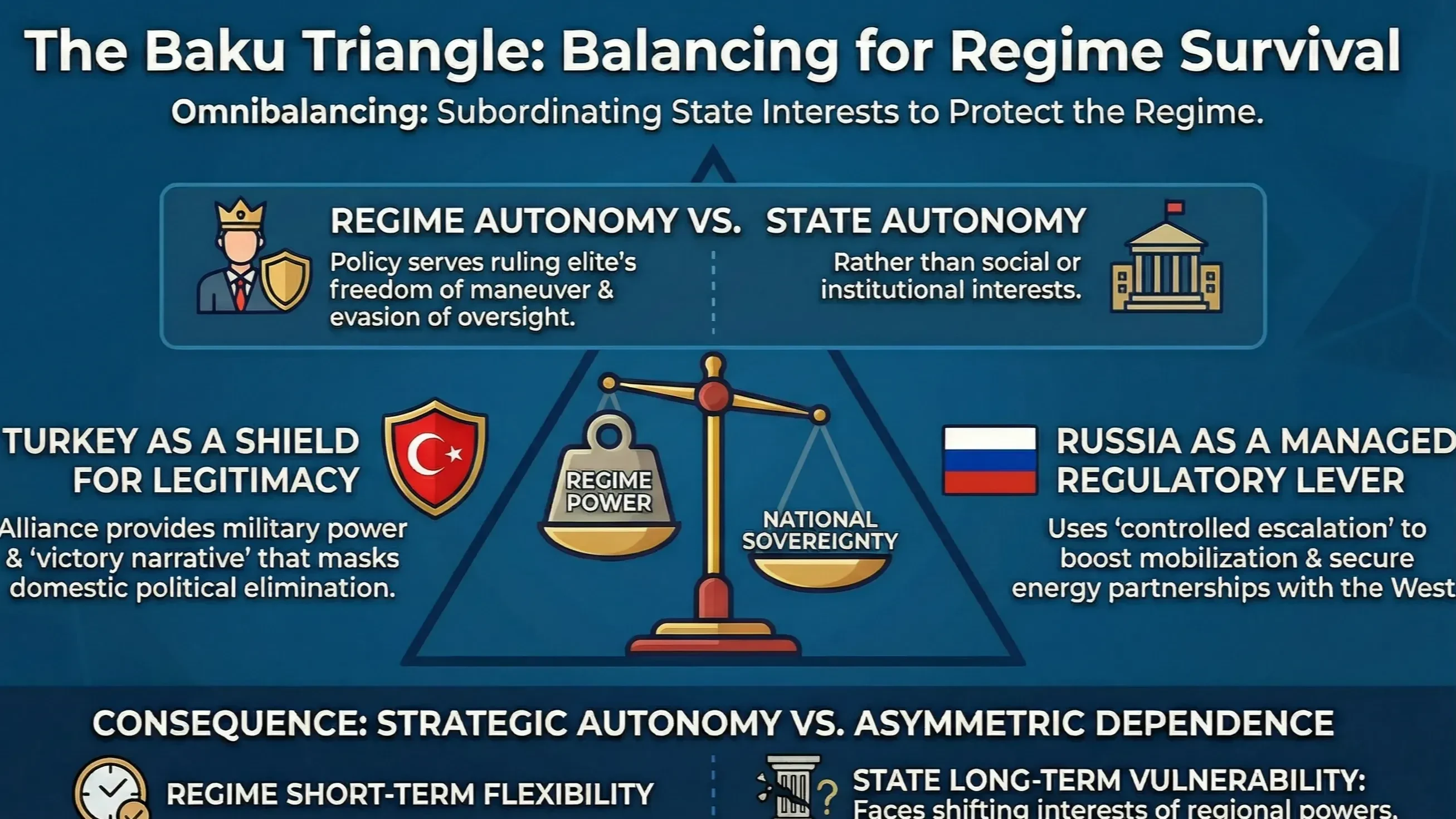

The point that the Azerbaijani ruling elite most frequently boasts about in foreign policy—and considers its greatest achievement—is its policy of balance / multi-vector diplomacy. This strategy is explained as one of sovereignty and strategic autonomy; however, in reality, this “autonomy” does not serve the Azerbaijani state as such, but rather opens up room for maneuver for the ruling elite in both domestic and foreign policy.

The concept of “autonomy” is evaluated at two distinct levels in theory as well: state autonomy and regime autonomy. At the core of state autonomy lie the demands and interests of social groups, classes, and society as a whole. States define goals that take these demands and interests into account and implement them accordingly (Skocpol, 1982). At the same time, state autonomy refers to the state apparatus (institutions) not being “captured” by internal networks of interest and not operating under their direct dictate when shaping policy; this is a dimension separate from the state’s capacity to implement policy (Landwall and Teorell, 2016). State autonomy is measured by the extent to which the state can make independent decisions both from domestic groups and from the international system (Nettl, 1968).

Regime autonomy, by contrast, refers primarily to the ruling elite’s freedom of maneuver: it emerges through decision-making within a narrow circle and through the evasion of internal oversight mechanisms. In authoritarian regimes, autonomy depends not on the strength of state institutions, but on the regime’s ability to manipulate internal opposition and external pressure (Levitsky and Way, 2010). In weak states, regime autonomy is high because leaders use state institutions (the army, police) not to serve national interests but as “private property” to protect their own power (Migdal, 1988).

There are three key factors that constitute the pillars of regime autonomy in foreign policy: survival, institutional independence, and financial autonomy. Survival manifests itself not in ensuring overall state security, but in the formation of foreign alliances aimed at protecting the regime from internal coups and threats. In political theory, this is referred to as “omnibalancing” (David, 1991). In this process, the regime subordinates state institutions and constitutional frameworks to its own political calculations, thereby gaining institutional independence (Skocpol, 1979). Financial autonomy, as noted in Hazem Beblawi’s “rentier state” model (Beblawi, 1987), allows the regime—thanks to external resource revenues such as oil—to avoid dependence on taxation, and thus to make decisions freely without accountability to domestic groups.

The multi-vector foreign policy course of official Baku is precisely a form of reverential diplomacy serving regime survival. The diplomatic reverences of the Aliyev regime, on the one hand, create conditions for the elimination of political competition, the systematic dismantling of media and civil society institutions, and the silencing of critical voices; on the other hand, this very landscape ensures that these contradictory reverences remain beyond debate.

Baku also structures its foreign alliances according to this scheme. When it moves excessively close to one side, it uses the existence of the other side as a “regulatory” lever, attempting to neutralize two (or more) major powers against each other. This line is especially evident in relations with Turkey and Russia and in Azerbaijan’s attempts to create a “balance” between these two powers. Baku keeps Turkey as a deterrent shield against Russia, while retaining Russia as a regulatory exit option against Turkey (and the West); what it calls balance is the simultaneous operation of these two levers.

In this article, the KHAR Center analyzes the contradictions of Azerbaijan’s balancing policy between Russia and Turkey.

Main Research Question

Does the Russia–Turkey balance provide Azerbaijan with strategic autonomy, or does it, by merging with the interests of an authoritarian regime, push the country toward asymmetric dependence?

The Authoritarian Regime as the Engine of “Balance”

Azerbaijan’s foreign policy balancing strategy is often explained through clichés such as an “energy state” or “leader diplomacy,” but this is a superficial assessment designed to conceal the core factor. The fundamental and stabilizing factor behind Baku’s balancing policy is the authoritarian nature of the political regime. Unlike countries where domestic political and societal oversight over foreign policy, accountability, and transparency exist, authoritarian regimes do not face a “problem of direction change,” because the decision-making mechanism is closed.

This difference is explained as a mechanism in international relations theory. According to James Fearon, as long as a leader’s retreat or contradictory maneuvers in foreign policy generate domestic audience (reputational) costs, the decision-maker’s room for maneuver narrows and it becomes harder to pursue “unquestioned” policies; in authoritarian regimes, however, such reputational costs are lower, foreign policy becomes more easily personalized, and it is tied to the agenda of a narrow circle (Fearon, 1994).

According to Robert Putnam, foreign policy decisions are not only an “interstate game” but also a domestic political game. Conceptualizing this as a two-level game, the author defines the first level as the international table—leaders, diplomats, interstate agreements—and the second level as domestic approval/ratification—parliament, government coalitions, intra-party balances, public opinion, and interest groups. According to Putnam, authoritarian regimes formally lack a second level; however, informal veto actors such as the military, security elites, oligarchy, and internal factions become prominent. Moreover, concerns over legitimacy and regime security can also function as second-level constraints. In other words, the two-level game is also applicable to authoritarian regimes, but its institutional form differs. From this perspective, to understand foreign policy, it is crucial not only to examine the interstate balance of power, but also to consider each country’s domestic political architecture and how this architecture affects the leader’s “win-set” (the set of international agreements that can be domestically accepted) (Putnam, 1988).

The existing domestic political architecture explains why Azerbaijan’s balancing policy can be managed “without debate”: as internal ratification and oversight barriers weaken, foreign policy turns into a technical instrument of a narrow circle, and parallel reverences toward different external actors do not generate domestic audience costs.

Assessments by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) of both the 2024 presidential election (ODIHR, 2024a) and the parliamentary elections held the same year (ODIHR, 2024b) demonstrate the absence of real political alternatives and severe restrictions on fundamental freedoms and the media. In particular, the contraction of the media space and the destruction of independent media ensure that the authorities are effectively freed from any “audit” over foreign policy decisions as well. Total and aggressive repression against independent media outlets and civil society representatives such as Abzas Media and Toplum TV (HRW, 2024), the excessive tendency to punish political opponents through imprisonment (BBC, 2025), and the absence of serious international reactions further enable the Azerbaijani ruling elite to make unquestioned and undebated decisions in foreign policy.

On the one hand, the Azerbaijani authorities sign the Shusha Declaration, declaring Ankara the main pillar of the security architecture (AzeMedia, 2021); on the other hand, they sign a declaration on allied cooperation with Russia. In a competitive and audited political system, each of these steps would require extensive explanation, parliamentary debate, media criticism, and strategic doctrine discussions. In a non-competitive and “unaudited” system, however, they can easily be “sold” under the label of “national interest.” This label has played a central role—especially after the Second Karabakh War—as a key slogan of the Azerbaijani authorities’ policy of eliminating criticism and political alternatives and transitioning toward dictatorship (KHAR Center, 13 January 2026).

This configuration creates no problems in relations with Turkey and Russia; on the contrary, compared to the status quo, a democratic Azerbaijan would be more “risky” for both countries. Here, it is not ideological affinity but pragmatic compatibility that prevails: for both Moscow and Ankara, rigid authoritarian governance in Baku means a predictable and “manageable” partner in the short term. Unlike a democratic partner, an authoritarian ally both implements decisions swiftly and manages a political course that does not encounter domestic resistance more comfortably.

Turkey — Legitimacy Production, Victory Partnership, and the Risk of New Dependence

In Azerbaijan’s reverential diplomacy constructed between Russia and Turkey, Turkey is not merely a “close partner”; it is presented as the pillar of the security architecture and, at the same time, as an actor that plays a direct role in producing domestic legitimacy for the ruling elite.

In particular, Ankara’s support during the contested presidential elections of 2003 (CSCE, 2003) and in the implementation of the succession plan prior to those elections (CACI Analyst, 2003) played a crucial role in Ilham Aliyev’s acquisition of international legitimacy and laid the groundwork for the subsequent development of bilateral relations. With the exception of the football match–flag–Karabakh protocols tension in 2009, which had effects lasting for some time (Asker, 2009), this line has remained largely uninterrupted.

The most decisive factor here has been Ankara’s choice to build its relations with Azerbaijan exclusively through the ruling elite, to act with maximum caution in its engagement with civil society and the opposition, and to support the government’s position on issues of democracy and human rights in the country. This approach, consistently pursued on international platforms as well, has turned the Erdoğan government into one of the main allies—indeed, protectors—of the Aliyev administration.

Relations with Ankara provide Baku, on the one hand, with military power, and on the other hand with symbolic capital (the presence of a major ally) necessary to sustain the victory narrative. Especially after the 2020 war, this symbolic capital became a key element of the authoritarian consolidation of Aliyev and Erdoğan. During the Second Karabakh War in 2020, Azerbaijani–Turkish political, military, and economic relations entered a new phase. Turkey played an exceptional role in the liberation of Azerbaijan’s occupied territories. Although between 2011 and 2020 Turkey ranked fourth—after Russia, Israel, and Belarus—in Azerbaijan’s arms imports (SIPRI, 2021), the technologies acquired from Ankara—particularly UAVs—had a disproportionate impact during the war and functioned as a “game changer” in terms of combat effectiveness (Kınık and Çelik, 2021).

This role was institutionalized with the Shusha Declaration signed in 2021. The Shusha Declaration, which expresses mutual support in the event of a “threat or attack,” is not merely a foreign policy document; it also serves as a framework that strengthens the “national interest” label for the Aliyev administration in domestic politics and foregrounds a security-centered discourse. As political alternatives are eliminated domestically, such documents turn into mutual “insurance”: closeness with Turkey creates a consolidation around “national interest” at home, and this consolidation, in turn, shields closeness with Turkey from scrutiny. Narratives of “brotherhood,” “victory,” and the “restoration of occupied territories” make it easier to frame criticism as “opposition to national interests.”

This scrutiny-free closeness also encompasses the personal economic interests of the authoritarian leaders of both countries. Both the Aliyev and Erdoğan administrations significantly benefit from the development of alliance relations in strengthening family capitals (and thus regime pillars). The activities in Azerbaijan of companies belonging to businessmen close to the Erdoğan government, known as the “Gang of Five” (Medyascope, 2021), and the Aliyev family’s open and covert investments in Turkey (Haber Sol, 2025) are clear examples of this. This mutual benefit also functions as reciprocal security insurance for both sides.

However, no matter how much mutual benefit and insurance persist, the political capital–sharing–averse nature of the two administrations (in reality, the two leaders) requires that the risk of dependence and tension always be kept in view. For example, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s statement in 2024, referring to Israel, that “just as we entered Libya and Karabakh, we could do the same to them” (Reuters, 2024), and the reaction of Azerbaijan’s official state newspaper with harsh phrases such as “we paid for every piece of ammunition down to the last penny,” “these statements pour water on the Armenian mill,” and “they are trying to appropriate the victory of our people, our army, and our commander” (Azerbaijan newspaper, 2024), constitute just one illustration of the tension inherent in the very victory that both sides take pride in.

In other words, on the one hand, Turkey is a partner and pillar of the Azerbaijani ruling elite’s legitimacy efforts built around victory—since relations with Ankara are packaged within the “national issue” framework, any questions or doubts on this matter can easily be neutralized, and all questionable operations acquire a status of immunity. On the other hand, both sides are highly sensitive about whose share in the victory coalition is greater—the clash between Erdoğan’s claims to regional leadership and a “big brother” role, and Ilham Aliyev’s ambition to be an absolute “victor” and “strong player,” becomes particularly acute at this point.

Although not openly articulated in official language, there is a prevailing opinion in pro-government circles in Turkey that Ankara was the key actor in liberating Karabakh from occupation, and that the Azerbaijani leadership should repay this debt through behavior aligned with Turkish policy. This sentiment is especially visible in media and social media discussions regarding the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The Azerbaijani ruling elite, however, reacts painfully to this burden of indebtedness—this is evident both in the angry tone of the above-mentioned article in Azerbaijan newspaper and in Ilham Aliyev’s statements such as “issues of the Arab world should be resolved by the Arab world” with regard to Palestine (Reuters, January 2026). This psychological-political framework of “indebtedness” may constrain Baku’s room for maneuver.

The second channel of linkage–dependence between Turkey and Azerbaijan lies in transit and energy routes. For Azerbaijan, Turkey is not only an ally but also the geopolitical gateway to the European market. TANAP and the Southern Gas Corridor provide Baku with both economic revenues—one of the main pillars of the ruling elite’s power—and resilience in the face of Western criticism. Here, there exists both a form of alliance among Russia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, and contradictions that are, for now, largely concealed. In particular, since Russia launched its total war against Ukraine in 2022, Europe’s need to diversify energy supplies has increased the role of both Azerbaijan and Turkey. Both countries benefit from the material and geopolitical advantages of this situation. At this juncture, Azerbaijan and Turkey effectively play the role of two joint substitutes for Russia. At the same time, however, there are substantial allegations and well-grounded suspicions regarding the “laundering” of Russian natural gas on European markets via Azerbaijan and Turkey. In this regard, the three countries operate within a coalition (KHAR Center, November 2025).

Yet both the allegations that Azerbaijan and Turkey are mediating the “laundering” of Russian gas on European markets (Van Rij, 2024), and U.S. pressure on Turkey to pursue energy diversification, reduce dependence on Russian gas, and pivot toward the LNG market, cast doubt on the long-term sustainability of these benefits. In a geopolitical system changing at a dizzying pace, such non-transparent operations may yield serious short-term gains, but they simultaneously create a nexus of threat and dependence.

The third, and perhaps most sensitive, aspect of the Turkish pillar is the illusion of perceiving Turkey as an “automatic balance” against Russia. For Baku, the Turkish factor plays a deterrent role vis-à-vis Moscow, but this role is never fully symmetrical. Turkey’s parallel relations with Russia—energy dependence, tourism, trade and security dialogues, the use of Russia as a shield against the West, and so on—create certain limits for Ankara. In other words, Turkey is not a stable and unconditional “shield” in Baku’s hands; it is an actor with its own agenda, which competes with Moscow in certain areas but more often and primarily seeks compromise.

This makes the Turkish leg of Azerbaijan’s reverential diplomacy both useful and uncertain: the language of alliance with Ankara provides Baku with both deterrence and bargaining leverage vis-à-vis Moscow. Through this closeness, Baku sends Russia the message “I am not alone” and neutralizes the likelihood of harsh escalation from Moscow. Yet this is not an unconditional lever, because Turkey’s parallel closeness with Russia also constrains Baku’s freedom of maneuver and calls into question its ability to take unilateral steps.

Russia — Neither an Old Friend nor a New Enemy

Just as the Azerbaijani ruling elite uses the Turkish factor as a security cushion against Russia, it also consistently pursues a policy of not fully severing ties with Moscow in order to balance the risks created by closeness with Turkey. This also functions as a defensive mechanism vis-à-vis the West.

The primary objective of the Azerbaijani leadership in its relations with Moscow is not to re-enter a “big brother–little brother” relationship with Russia, but to keep Russia at a manageable level of risk. This is because unequivocal closeness with Russia is, first of all, risky in terms of Ilham Aliyev’s deepening of authoritarianism at home and the elimination of the last remaining signs of democracy—accepting Moscow’s patronage could reduce the West’s “tolerance” toward the Azerbaijani leadership. At the same time, a complete rupture with Russia runs counter both to the anti-democratic nature of the Aliyev regime and to its interests. Maintaining a distant form of closeness with Moscow under the veil of “sovereignty” expands the Azerbaijani leadership’s room for reverential maneuvering.

The alliance declaration signed between the two countries on 22 February 2022—two days before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine—which included formulas such as “non-interference in internal affairs,” sovereignty, and security, represents the institutionalized form of these relations based on mutual maneuvering (President Az, 2022). On the other hand, however, official Baku has sought to reduce Russia’s leverage, particularly by relying on Turkey’s military, technical, and political support. The document that ended the Karabakh war in 2020 conditioned Russia’s physical presence (peacekeepers) on Azerbaijani territory and stood out as one of Moscow’s most important levers. Yet the outbreak of the war in Ukraine created a window of opportunity for Azerbaijan on this issue—the Russian peacekeeping contingent withdrew from Karabakh (AP, 2024), and the Russian–Turkish joint monitoring center located in Aghdam ceased operations (Interfax, 2024). Naturally, the Azerbaijani leadership also credited the withdrawal of Russian peacekeepers from Karabakh to its own “victory ledger,” but subsequent developments showed that this was far from the only lever Russia could use against Baku, and in comparison with other levers it was, in fact, a largely symbolic development.

In other words, this was not a case of “the Russian troops left and the problem ended”; on the contrary, it became apparent afterward that even without a military contingent Russia is not an actor from which Baku can easily disengage. Trade and transit networks, the diaspora, the political use of migration channels, information and cultural influence infrastructures, and leverage through the ability to “slow down or accelerate” regional processes all remain threats to both Azerbaijan’s sovereignty and the regime’s freedom of maneuver (Kitachaev, 2025a).

The cycles of escalation and de-escalation between Moscow and Baku in 2024–2025 were significant in terms of observing both the nature of this threat and the Azerbaijani leadership’s behavior in response to it. In December 2024, Russian air defense systems shot down an AZAL passenger plane, which subsequently crashed near the port of Aktau in Kazakhstan, killing 38 people. When Russia attempted to cover up the incident, Ilham Aliyev, several days after the tragedy, demanded that Russia “admit its guilt” and assume responsibility, calling Moscow’s initial reactions “absurd versions” (Reuters, 2024). Several months later, in June 2025, Aliyev again publicly called on Russia to openly acknowledge that it had accidentally shot down the aircraft and to punish those responsible (Reuters, 2025).

This tension was later followed by pressure on representatives of the Azerbaijani diaspora in Russia and Azerbaijan’s retaliatory moves. In June 2025, Russian security services raided the home of an Azerbaijani family in Yekaterinburg under the pretext of an “anti-terror operation,” during which two Azerbaijani citizens were killed. Azerbaijan issued a formal protest note to Russia in response (MFA, 2025). Official Baku not only accused Russian security forces of deliberately killing Azerbaijanis, but also canceled all cultural events related to Russia, conducted a raid on the Baku office of Russia’s Sputnik agency and detained its staff. In addition, based on photographs later circulated, several Russian IT specialists who appeared to have been beaten were also detained and charged with drug trafficking and cyber fraud. Cultural centers operating under the “Rossotrudnichestvo” framework and the offices of several associations were inspected, and equipment and documents were seized (The Guardian, 2025). In Russia, meanwhile, Azerbaijani diaspora activists and business owners in various cities were subjected to tighter inspections, questioning, administrative pressure, and public humiliation (AP, 2025).

Despite these episodes and the short-lived propaganda narrative that “Aliyev is challenging Putin,” in October 2025 Ilham Aliyev significantly softened his tone, thanking Putin separately for “detailed information” about the investigation he had conducted, stating that “we never had any doubt that everything would be resolved objectively,” and emphasizing that relations between the two countries were “successfully developing” in all areas and that there had been “no slowdown” in trade or other directions (AA, October 2025). With this statement, the episodes of tension came to an end, and the anti-Russian rhetoric in Azerbaijani state media faded as quickly as it had risen…

These episodes demonstrated that Baku can use controlled escalation not only as a defensive reaction but also as a calculated political instrument. The cycles of tension and relaxation revealed the potential dividends of controlled confrontation with Moscow for Baku. The first dividend was boosting domestic mobilization through harsh rhetoric. As time passes since the Karabakh victory, societal mobilization around the “iron fist” diminishes. The “Karabakh-sized grievance” that for years masked income inequality, impoverishment, corruption, pressure on civil society, and deepening authoritarianism in the country—and the euphoria of the “victorious leader” that legitimized this masking—are losing their relevance. A new national (or security) problem, or a new external enemy, can thus become a vital source of nourishment for the continued legitimization of authoritarianism. However, a new conflict with Armenia is not desirable for the regime itself, nor does it appear likely that its ally Turkey would support such a move. In this context, challenging an external enemy “as big as Russia” serves the Azerbaijani leadership’s interest in sustaining authoritarian legitimacy.

The second dividend was demonstrating the possibility of raising the price through selected levers. The conflicts showed how quickly and easily diaspora, migration, and information tools can be transformed into instruments of pressure in Russia–Azerbaijan relations. Azerbaijan’s protest note, the cancellation of cultural events and visits, the raid on the Sputnik office, the closure of the “Russian House,” the demonstrative detention and beating of Russian citizens all indicated that these tools are also part of Baku’s own “pricing package.”

The third dividend was securing insurance from the West. Azerbaijan has long sought to present itself in the West as a reliable energy partner and a stable, secular power in the region. Yet this image is constantly undermined by waves of domestic repression. The current tension with the Kremlin helps redirect Western attention away from Baku’s internal violations toward its “independent,” even “anti-Russian,” posture. In other words, through this conflict Baku seeks to appear not as Russia’s authoritarian ally but as the West’s strategic partner—especially in the energy sphere—in the global confrontation with Russia. The price of this is Brussels’ and Washington’s willingness to turn a blind eye to Azerbaijan’s domestic problems (Kitachaev, 2025b).

At the same time, while benefiting from the advantages of tension with Russia, Ilham Aliyev seeks to prevent the process from spiraling out of control. The country’s authoritarianization and the silencing of all critical voices allow him to sustain, without scrutiny, the image of a leader who can both “challenge Russia” and “be friends with Russia.”

For this reason, the parties can easily abandon enemy rhetoric and continue as if nothing had happened. Russia is one of Azerbaijan’s largest suppliers of components, fuel, and other raw materials, and also an important market for Azerbaijan’s agricultural products. Moreover, approximately 46 percent of remittances to Azerbaijan come from Russia; according to official data, more than 300,000 Azerbaijani migrants live and work in Moscow alone. If the Kremlin were to take steps that significantly complicated the lives of these labor migrants, Baku would face both economic losses and domestic political risks associated with the return of migrants (Kitachaev, 2025c).

In short, the Azerbaijani authorities seek to score points both domestically and internationally by managing relations with Moscow through controlled tension, without fully severing economic and political ties with Russia. When problems arise in relations with the West, these maneuvers operate in the opposite direction—when human rights and democracy issues come onto the agenda, the Moscow channel is used as a message that “we have other options.”

Structurally, the Russian track is less a framework for expanding autonomy than one that conditions it and creates the risk of asymmetric dependence. First, Russia’s approach toward post-Soviet countries is built on dependence—Moscow does not treat these states as equal partners. Second, the Azerbaijani leadership’s understanding of strategic autonomy consists of regime autonomy, and this approach generates the risk of asymmetric dependence across all relationships. This risk is especially high in relations based on power rather than norms. Baku attempts to insure itself against this dependence risk vis-à-vis Russia through third actors (Turkey or the West) and controlled tensions.

Conclusion

The dynamics of relations with Russia and Turkey show that Baku’s foreign policy maneuvers serve not to strengthen state autonomy but rather the regime’s domestic legitimacy and international security needs. The “victory partnership” and military closeness with Turkey are presented to society as a “national interest” (and indeed receive substantial resonance), masking the elimination of internal oversight. This allows the ruling elite to use foreign policy to insure its own interests and personal (family) capital, thereby creating “regime autonomy.” In other words, the alliance with Turkey functions primarily as a shield for the ruling elite.

On the other hand, the zigzags of tension and relaxation with Russia demonstrate that Azerbaijan’s foreign policy strategy is built not on stable principles but on temporary price-setting bargaining aimed at regime survival. The absence of institutional state defense mechanisms against Moscow’s leverage in migration, trade, and security leaves the country vulnerable to asymmetric dependence.

As a result, the Russia–Turkey balance does not provide Azerbaijan with stable strategic autonomy; on the contrary, it expands pathways of asymmetric dependence and turns Azerbaijan into a more exposed actor, open to the influence of both the domestic and foreign policy interests of two regional powers. In other words, the real outcome of this balance is not state autonomy but an expansion of the regime’s room for maneuver. This model may appear flexible in the short term, but in the long run it renders foreign policy more fragile and sensitive to channels of dependence. When regional power balances shift or relations among major actors take on new forms, the cost of this flexibility for the country may be high.

References

Skocpol, Theda, 1982. Bringing the State Back İn. A Report on Current Comporative Research on the Relationship between States and Social Structures. https://items.ssrc.org/from-our-archives/bringing-the-state-back-in-a-report-on-current-comparative-research-on-the-relationship-between-states-and-social-structures/

Lindvall, Johanne and Teorell Jan, 2016. STATE CAPACITY AS POWER: A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK. https://ces.fas.harvard.edu/uploads/files/events/State-Capacity-as-Power-September-2016.pdf

Nettl, John Peter, 1968. The State as a Conceptual Variable. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/world-politics/article/abs/state-as-a-conceptual-variable/B367A80AE747AB6FDB74643E161C27B5

Levitsky, Steven & Way, Lucan, 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War, səh. 54-58

Migdal, Joel S, 1988. Strong Societies and Weak States, səh. 206-210.

David, Steven R, 1991. Explaining Third World Alignment. World Politics 43, no. 2, s 233–256.

Skocpol, Theda, 1979. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Beblawi, Hazem, 1987. The Rentier State in the Arab World. In The Rentier State, edited by Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani, 49–62. London: Routledge.

Fearon, James D, 1994. Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes. https://web.stanford.edu/group/fearon-research/cgi-bin/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Domestic-Political-Audiences-and-the-Escalation-of-International-Disputes.pdf

Putnam, Robert D, 1988. Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games. https://www.guillaumenicaise.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Putnam-The-Logic-of-Two-Level-Games.pdf

OSCE/ODIHR, 2024a. Lack of genuine political alternatives in a restricted environment characterized Azerbaijan’s presidential election, international observers say. https://odihr.osce.org/odihr/elections/azerbaijan/562494

OSCE/ODIHR, 2024b. Azerbaijan’s elections devoid of real competition amid diminishing respect for fundamental freedoms, but efficiently prepared: international observers. https://odihr.osce.org/odihr/elections/575509

Human Rights Watch, 2024. “We Try to Stay Invisible”: Azerbaijan’s Escalating Crackdown on Critics and Civil Society. https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/10/08/we-try-stay-invisible/azerbaijans-escalating-crackdown-critics-and-civil-society

BBC News Azərbaycanca, 2025. AXCP sədri Əli Kərimlinin həbs olunduğu bildirilir. https://www.bbc.com/azeri/articles/cn09yd16nr5o

AzeMedia, 2021. The full text of the Shusha Declaration. https://aze.media/the-full-text-of-the-shusha-declaration/

Fəttah, Elman, yanvar 2026. Qələbədən sonra sərtləşmə: Azərbaycan avtoritarizminin diktaturaya keçid trayektoriyası. Khar Center. https://www.kharcenter.com/arasdirmalar/qelebeden-sonra-sertlesme-azerbaycan-avtoritarizminin-diktaturaya-kecid-trayektoriyasi

Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, 2004. Azerbaijan Elections. https://www.csce.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Azerbaijan-Elections_0.pdf

CACI Analyst, 2003. AZERI PRIME MINISTER ILHAM ALIYEV RECEIVED INVITATION TO PAY OFFICIAL VISIT TO TURKEY TO GET SUPPORT OF ANKARA. https://www.cacianalyst.org/component/k2/item/8306-news-digest-caci-analyst-2003-8-8-art-8306.html

Asker Ali, 2009. Tehlikeli Üçgen: Türkiye-Ermenistan-Azerbaycan. Yüzyıl Türkiye Enstitüsü. https://21yyte.org/guney-kafkasya-iran-pakistan-arastirmalari-merkezi/tehlikeli-ucgen-turkiye-ermenistan-azerbaycan/2998

SİPRİ, 2021. Arms Transfers to Conflict Zones: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh. https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2021/arms-transfers-conflict-zones-case-nagorno-karabakh

Kınık, Hülya və Çelik, Sinem, 2021. The Role of Turkish Drones in Azerbaijan’s Increasing Military Effectiveness: An Assessment of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. İnsight Turkey. https://www.insightturkey.com/articles/the-role-of-turkish-drones-in-azerbaijans-increasing-military-effectiveness-an-assessment-of-the-second-nagorno-karabakh-war

Medyascope, 2021. Son Karabağ Savaşı’nın tek galibi Azerbaycan değil: aralarında Cengiz, Kalyon, Demirören, Kolin ve Özgün’ün olduğu Türk firmalarına milyonlarca dolarlık ihale verildi. https://medyascope.tv/2021/06/11/son-karabag-savasinin-tek-galibi-azerbaycan-degil-aralarinda-cengiz-kalyon-demiroren-kolin-ve-ozgunun-oldugu-turk-firmalarina-milyonlarca-dolarlik-ihale-verildi/

Haber Sol, 2023. Aliyevlerin Bodrum sevdası ve gayrimenkul serveti: Erdoğan’ı ziyaretinden önce dikkat çeken. https://haber.sol.org.tr/haber/aliyevlerin-bodrum-sevdasi-ve-gayrimenkul-serveti-erdogani-ziyaretinden-once-dikkat-ceken

Reuters, 2024. Erdogan says Turkey might enter Israel to help Palestinians. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/erdogan-says-turkey-might-enter-israel-help-palestinians-2024-07-28/

Azərbaycan, 2024. Qarabağ zəfərinin müəllifi müzəffər Ali Baş Komandan və Azərbaycan Ordusudur. https://www.azerbaijan-news.az/az/posts/detail/qarabag-zeferinin-muellifi-muzeffer-ali-bas-komandan-ve-azerbaycan-ordusudur-1722458765

Reuters, yanvar 2026a. Azerbaijan will not send peacekeepers to Gaza, president says. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/azerbaijan-will-not-send-peacekeepers-gaza-president-says-2026-01-05/

KHAR Center, 2025. Kiçik tədarükçüdən geosiyasi aktora: Azərbaycanın enerji kartı avtoritar idarəetmənin qalxanı kimi. https://www.kharcenter.com/nesrler/kicik-tedarukcuden-geosiyasi-aktora-azerbaycanin-enerji-karti-avtoritar-idareetmenin-qalxani-kimi

Van Rij Armida, 2024. The EU’s continued dependency on Russian gas could jeopardize its foreign policy goals.

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/06/eus-continued-dependency-russian-gas-could-jeopardize-its-foreign-policy-goals

President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, 2022. Declaration on allied interaction between the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Russian Federation. https://president.az/en/articles/view/55498

Associated Press, 2024. Russia begins withdrawing peacekeeping forces from Karabakh, now under full Azerbaijan control. https://apnews.com/article/russia-azerbaijan-withdrawal-f60ed4e9ca5e78c071b77a2fa57cd765

Interfax, 2024. Turkish-Russian monitoring center in Karabakh ceases operations. https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/101829/

Kitachaev, Bashir, 2025a. Why Is Azerbaijan Ramping Up Tensions With Russia? https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2025/07/azerbaijan-russia-arguments?lang=en

Reuters, 2024. Azerbaijan president says crashed plane was shot at from Russia. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/azerbaijan-pays-tribute-pilots-passengers-who-perished-air-crash-2024-12-29/

Reuters, 2025. Azerbaijan leader says he wants Russia to admit it accidentally shot down passenger plane killing 38. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/azerbaijan-leader-says-he-wants-russia-admit-it-accidentally-shot-down-passenger-2025-07-19/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Azerbaijan, 2025. (No. 287/25). https://mfa.gov.az/az/news/no28725

The Guardian, 2024. Officials report 29 survivors and 38 killed as plane crashes in Kazakhstan. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/25/kazakhstan-plane-crash-aktau-azerbaijan-airlines-baku-grozny-fog-chechnya

Associated Press, 2025. Tensions are rising between Russia and Azerbaijan. Why is this happening now? https://apnews.com/article/russia-azerbaijan-putin-aliyev-tensions-relations-627104d770071082be26c189161b1ac9

AA, 2025. Azerbaijan terminates operations of Russian House in Baku. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/azerbaijan-terminates-operations-of-russian-house-in-baku/3474115

Kitachaev, Bashir, 2025b. Why Is Azerbaijan Ramping Up Tensions With Russia? https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2025/07/azerbaijan-russia-arguments?lang=en

Kitachaev, Bashir, 2025c. Why Is Azerbaijan Ramping Up Tensions With Russia? https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2025/07/azerbaijan-russia-arguments?lang=en