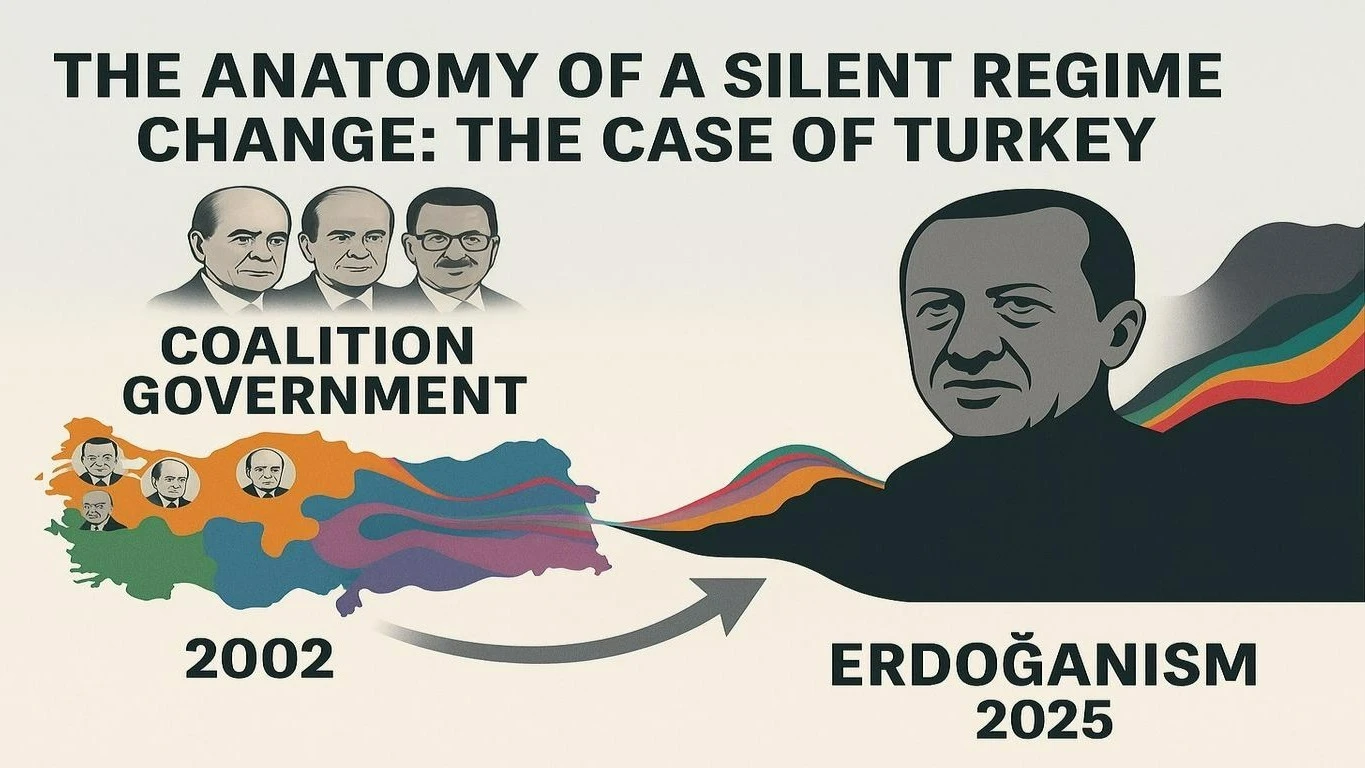

This research explores the silent regime change that has occurred in Turkiye since the early 21st century through political, legal, and ideological lenses. The main focus is on the transition from a parliamentary system to a presidential system under the leadership of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and how this transition—under the guise of democratic procedures—paved the way for authoritarian consolidation.

Utilizing methods such as historical-institutional analysis, discourse analysis, legal inquiry, and political psychology, this study reveals the processes of political power centralization, the erosion of the functionality of legal institutions, and the tightening control over media and opposition. The main objective is to show how democracy in Turkiye has been gradually eroded within formal frameworks, how the centralization of political power has marginalized the opposition, how legal institutions have become dysfunctional, and how the public will has been manipulated through populist rhetoric and politics of fear.

Furthermore, this material aims not only to present facts to the reader but also to help them understand the structural links between these facts, recognize the new forms of authoritarianism in the 21st century through the Turkish case, and reflect on civic consciousness and ways of democratic resistance.

In this analysis, the Khar Center seeks to demonstrate that regime changes are not merely legal and political events but are also intertwined with cultural, social, and psychological processes. The goal is to encourage readers to understand—through the example of Erdogan’s Turkiye—how fragile democracy can be, and how flexible and multifaceted autocracy can become.

Keywords: Turkiye, regime change, authoritarianism, populism, polarization, Erdoganism, presidential system, democracy, AKP

Main Question: How did regime change occur in Turkiye, and through which legal, political, and ideological mechanisms was this process legitimized and made acceptable to the public?

Introduction

At the beginning of the 21st century, Turkiye was a country advancing toward liberal democracy, negotiating membership with the European Union, and experiencing a period of economic rise (Müftüler-Baç 2005). Political pluralism, a free media, judicial independence, and the peaceful transfer of power through elections were presented as core indicators of Turkish democracy. However, behind this bright façade, the political system was gradually and deliberately transforming into a centralized regime (Yılmaz & Bashirov 2022).

When Erdogan came to power as Prime Minister in 2003, he used his political skill, populist rhetoric, and ability to exploit political voids to chart a path that appeared democratic at first but was filled with autocratic intentions. His famous remark “democracy is not a goal for us, it is a means” openly declared the ideological and strategic essence of this approach (Erdogan 1997).

Theoretical Perspective: The Social Dynamics of Ideological Polarization and Authoritarian Consolidation

Transitions from democracy to authoritarianism in modern political regimes rarely happen overnight. Rather, these transitions are the result of deep social, ideological, and institutional changes that occur gradually. In political science, this phenomenon is referred to as “gradual authoritarian consolidation” (Linz & Stepan 1996). One of the earliest and most critical stages of such transformations is the deliberate erosion of public consensus and a policy of systematic polarization.

Polarization is the cultivation of deep ideological, cultural, and ethnic divisions between social groups. It is a strategy frequently employed by authoritarian regimes to maintain public support (McCoy, Rahman, Somer 2018). In such contexts, principles of common ground and checks and balances weaken, and public and political life transforms into a battle between “us” and “them.” As a result, political rivals are portrayed not as legitimate alternatives but as “traitorous enemies.” As Jennifer McCoy and colleagues note, “pernicious polarization” creates a conducive social environment for regimes to dismantle democratic institutions.

In the Turkish case, this process intensified under Erdogan’s leadership, particularly from the 2010s onward. The AKP, which came to power in 2002, initially gained broad social support with its discourse of moderate Islamism and democratic reforms (Yavuz 2009). However, from 2011 onward, the party’s governance style gradually leaned toward authoritarian tendencies. Commonly used rhetorical expressions such as “national will,” “mastermind,” “local and national stance,” and “internal and external enemies” began to frame dissenters as enemies of the people (Taş 2015).

This dual discourse sharply divided society into ideological blocs: “us” (the nation, patriots, local-national forces) and “them” (the elite, secular liberals, Western-oriented opposition, the “Fethullah Gulen Movement,” ethnic and religious minorities). This aligns with Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe’s concept of hegemonic politics built on “friend-enemy distinctions” (Laclau & Mouffe 1985). This strategy not only led to social fragmentation in Turkiye but also delegitimized opposition political actors (Gürsoy 2017).

The activities of political opposition, NGOs, universities, and the free media were often framed as being “against national interests,” as “sedition,” “treason,” or linked to “terrorism” (Es Murat 2020). These types of discourse had legal consequences—for example, with emergency decrees (KHK), thousands of public employees were dismissed without court decisions, and academics, journalists, and politicians were arrested en masse (Freedom House 2023; Amnesty International 2022).

As a result of this strategic polarization, democratic norms such as shared history, equality before the law, and dialogue with political opponents were devalued. One segment of society began to see itself as the “sole representative of the people,” while the other was marginalized, pushed out of public life, even criminalized (Tugal 2016). Political struggle ceased to revolve around programs and ideas and instead became framed in existential terms like “survival vs. extinction,” “faith vs. betrayal,” “enemy vs. friend.” Referencing Carl Schmitt’s concept of politics based on the “friend-enemy” distinction, political activity in Turkiye shifted from democratic debate to existential confrontation (Schmitt 2007).

This polarization changed the nature of elections. Although elections formally continued, they no longer served as democratic tools for legitimacy but became mechanisms to renew power through loyal electorates (Levitsky & Ziblatt 2018). Public opinion, shaped systematically, began to perceive alternative voices as “threats that must be silenced,” resulting in a paradox where democratic processes gradually destroyed themselves.

The Erdogan–Gulen Alliance and the West's “Moderate Islam” Doctrine: Anatomy of Turkish Politics from 2002–2013

The Political Architecture of the Erdogan–Gulen Partnership (2002–2013):

This period marked the close cooperation between Erdogan and the Gulen movement. The Gulen network derived its strength from parallel structures established within the bureaucracy, especially in education, the police, and judiciary. This network played a key role in enabling the AKP to gain full control over the state apparatus. Thanks to this partnership, hardline secular structures within the military were eliminated (through the Ergenekon and Balyoz trials), and the AKP consolidated its power (Gürsoy, 2012). During this period, Gulen’s schools and media outlets (Zaman, Samanyolu TV, etc.) legitimized AKP policies and promoted the “Turkish Islam” model internationally. Gulen, based in the U.S., was presented as a “reformer of Islam” in Western policy circles.

The West’s Search for a “Model”:

Western think tanks such as RAND Corporation and Brookings began promoting “progressive,” “Western-oriented,” and “democracy-friendly” Islamist models in the early 2000s. In RAND’s 2004 report (“Civil Democratic Islam”), Fethullah Gulen, his educational network, and civil society initiatives were praised as exemplary within this “constructive Islamism” framework (Rabasa & Benard, 2004).

Turkiye’s Geopolitical Appeal:

Turkiye’s role as a NATO member contributing to regional stability, its aspiration for EU membership, and its embrace of market economics made it an ideal laboratory for “Islamic democracy.” During this period, the AKP’s reformist rhetoric, commitment to liberal economics, and messages of “religious tolerance” were well-received in Washington and Brussels.

Ideological Symbiosis and Power Sharing Within the State:

The cooperation between AKP and the Gulen movement was ideologically framed within Islamist modernism. Both actors united to challenge the secular hegemony of the deep state (military, judiciary, and security elite) through “cultural Islamization.” Gulen’s influence in policing, justice, and education underpinned the institutional hegemony of the AKP. For example, in the 2007 “Ergenekon” and 2010 “Balyoz” trials, the secular elite within the military was neutralized via the judiciary. Although the evidence used in these trials was later found to be fabricated, both the AKP and the Gulen movement enjoyed Western silence or indirect support at the time (Jenkins, 2009). Simultaneously, the Gulen movement carried out “soft Islamization” via newspapers, TV stations, news agencies, and hundreds of schools and associations, both within Turkiye and globally—especially in Central Asia, the Balkans, and the U.S.

Despite increasing arrests of journalists, political pressure on the opposition, and judicial politicization from 2007 to 2013, the U.S. and EU often reacted mildly. Justifications like “strategic partnership” and “blocking regressive forces” led them to either overlook or openly support these trends. In the West’s quest for a “reformist ally” in the Islamic world, Erdogan and Gulen were seen as ideal partners. However, this alliance ultimately proved unreliable and dangerous.

The Peak of Erdogan–Gulen Tensions:

In 2013, the corruption scandal exposed by prosecutors linked to the Gulen movement—known as the 17–25 December events—ended the alliance. Erdogan labeled the movement a “state within a state” and launched a sweeping purge.

The West’s Dilemma and Ambiguity:

In this conflict, the West hesitated to take sides. On one hand stood Gulen, a long-time proponent of “moderate Islam,” and on the other, Erdogan, a strategic NATO ally. However, the U.S.'s refusal to extradite Gulen further strained relations with Erdogan’s regime.

The Collapse of the “Moderate Islam” Project and the Consolidation of Erdoganism

The “Turkish model,” built on the Erdogan–Gulen partnership, collapsed by the mid-2010s. It preserved neither democratic institutions nor managed to bridge Islam and liberalism. Instead, it fostered authoritarianism, corruption, and parallel power structures within the state.

After 2015, Erdogan shifted to a different political trajectory: all Gulen-linked structures were eliminated, an authoritarian regime was established through the presidential system, relations with the West deteriorated, and Turkiye turned toward Eurasianist and nationalist rhetoric. The “moderate Islam” project, in essence, laid the groundwork for a harsher regime.

The “2002–2015 period” represents a turning point both for domestic Turkish politics and for the West’s approach to the Islamic world. The Erdogan–Gulen partnership was a product of the symbiosis between Western ideological aspirations and realpolitik. Yet this partnership ultimately led to institutional breakdown, the weakening of the rule of law, and the rise of a new authoritarianism—Erdoganism.

Although the Erdogan–Gulen alliance was shaped within the framework of the West’s “constructive Islamism” model, it ended with both the instrumentalization of liberal values and the authoritarian evolution of political Islamism. This experience should not only be read as a case study of Turkiye but also as a failure of the West’s broader model for engaging with the Islamic world.

The Rise of Erdoganism: A Polished Transition to Authoritarianism

Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s 1997 statement that “Democracy is like a tram; we get off when we reach our destination” clearly demonstrated his view of democracy as merely a tactical tool (BİANET 2021). Although the AKP’s rise to power in 2002 was initially characterized by goals such as democratization and integration into the EU, this period was more of a springboard for establishing political hegemony. Erdogan’s political strategy involves not only Islamist-populist rhetoric but also the instrumentalization of national identity, religion, and historiography as political weapons. Erdoganism builds a philosophy of power based on Ottoman nostalgia, divine sovereignty, and the concept of the “national will” (Erdogan 1994).

One of the main pillars of Erdoganism is “religious nationalism.” In the AKP’s policies, Islam is not only presented as a matter of personal belief but also as a central value shaping the behavior of the state and citizen. In this way, religious voters are mobilized while the secular segments of society are marginalized (Tuğal, 2013). On the other hand, the populist character of Erdoganism undermines classical representative institutions by establishing a direct relationship between the citizen and the leader.

Erdoganism does not only strengthen control over political institutions but also constructs a new cultural hegemony. Censorship and ideological steering in the fields of art and cinema are parts of this policy. This policy, aimed at normalizing culture and transforming alternative lifestyles, constitutes a form of cultural authoritarianism (Baykan, 2021). Through this new cultural policy, authoritarianism is normalized not only in the legal and political system but also in everyday life. People are pushed to reconcile with the loss of democracy, and this process is carried out gradually under the guise of “security,” “stability,” and “traditional values.”

The rise of Erdoganism, unlike classical authoritarianism, is a process that unfolds within legal frameworks and electoral formalities but is accompanied by deep democratic erosion. This can be defined as a model of “polished authoritarianism”—a series of successive transitions in which the names of democratic institutions remain, but their functions are transformed.

In this sense, the year 2010 can be considered the first turning point in Turkiye’s political history, marking the beginning of a stage in which authoritarianism took on a more refined and legally veiled form. It was precisely during this period that the functionality and normative nature of democratic institutions in Turkiye began to erode gradually.

This period can also be characterized as the peak of the political alliance between the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the Fethullah Gulen Movement. The tactical cooperation formed between the AKP and the Gulen Movement since the early 2000s was particularly used to shift the internal balance of power in the state through the legal system and security apparatus (Taş 2018). The constitutional referendum held in 2010 was a clear result of this cooperation: through changes in the composition of the judiciary, jurists close to the Gulen Movement were appointed to institutions like the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court (Jenkins 2011). This accelerated the process of transforming legal institutions into tools for political purposes.

One of the most noteworthy aspects of all these changes is that they were initially implemented under the guise of broad public support, referenda, and “reform.” Thus, authoritarian tendencies did not emerge suddenly through violent coups but evolved from within democratic procedures toward “electoral authoritarianism.” As emphasized by Levitsky and Ziblatt, this process is a clear example of the phenomenon of democracies being dismantled from within (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018).

From 2015 onward, the complete transformation of the relationship between the AKP and the Gulen Movement into open hostility marked the beginning of a new phase of radical confrontation in Turkiye’s politics. Although this confrontation became visible with the corruption operations of December 17–25, 2013, it was accompanied by harsher political and administrative measures from 2015 onward. The large-scale campaigns conducted under the name of purging Gulen-affiliated cadres within the state became both a response to a real threat and an opportunity for Erdogan to consolidate power. This process reached its climax with the failed coup attempt on July 15, 2016. Erdogan responded not only with calls for political stability and national unity but also used the ensuing state of emergency to initiate wide-ranging changes aimed at redesigning the institutional system (Yabanci 2019).

Under the state of emergency declared after the coup attempt, thousands of civil servants, academics, and journalists were dismissed or arrested; media outlets were shut down, and civil society organizations were dissolved. In this environment, Erdogan legitimized his political model through the discourse of “national will” and ensured the transition from a parliamentary system to presidential rule through constitutional amendments in 2017.

Thus, the 2016 coup attempt provided both the ground for deepening authoritarianism and a legitimizing mechanism for Erdogan to redesign the political system.

The key turning point in Turkiye’s authoritarian consolidation was the 2017 Constitutional Referendum. As a result of the referendum, the parliamentary system was abolished, and a strong presidential regime was established. Turkiye transitioned from a typical “illiberal democracy” to an authoritarian governance model (European Society and Politics, 2017).

The main pillars of regime change can be summarized as follows:

- Concentration of Power: Legislative, executive, and judicial powers were subordinated to the will of the president. The principle of “checks and balances” enshrined in the Constitution was effectively abolished.

- Distortion of the Rule of Law: Law became subordinate to political power. Courts and the prosecution became tools of pressure against the opposition, and legal decisions were tailored to political interests.

- Inhibition of Political Competition: Although elections are held, they are not conducted under equal conditions. The media environment, financial resources, and legal frameworks favor government candidates.

- Deepening of Social Polarization: A large segment of society is now shaped not by discussion and consensus but by loyalty and the construction of enemy images, leading to the erosion of democratic civic consciousness.

- Economic and Institutional Collapse: The central bank, universities, independent institutions, media, and civil society have been dismantled. All power is concentrated in a single center — the presidential palace. This aligns with regime types known as “competitive authoritarianism” (Esen, Berk, and Şebnem Gümüşçü 2016).

Centralization of Legal and Institutional Structures

With the new governance system enacted in 2018, executive power was almost entirely subordinated to the president. Through presidential decrees, the functional role of parliament was sidelined, the institution of the prime minister was abolished, and central administrative bodies were directly subordinated to the president (Yılmaz and Bashirov 2022). This model resembles the governance form that O'Donnell called “delegative democracy”—where elected leaders, though formally within constitutional boundaries, rule in a Caesarist or Bonapartist style free from checks and controls (O’Donnell 1994).

The abolition of the separation of powers between legislative, judicial, and executive branches marked Turkiye’s departure from the rule-of-law model. The president’s dominant role in judicial appointments severely damaged judicial independence. Analyses show that since 2020, the Constitutional Court and other judicial institutions have issued decisions that align with the interests of the government (Kurban 2021).

Systematic Restriction of Freedom of Expression

The weakening of independent media and regulation of digital platforms through censorship is a common strategy of authoritarian regimes. The social media and “anti-disinformation” laws adopted in 2020 enabled the expansion of de facto censorship into the digital realm (Freedom House 2023). These laws, by criminalizing vague expressions such as “spreading false information,” restrict freedom of expression and are used as tools to silence independent media.

As noted in Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch reports in 2022, the systematic arrest of journalists, internet censorship, and economic pressure on the media have significantly increased in Turkiye (HRW 2022). This makes the concept of “digital authoritarianism” highly relevant to Turkiye (Howard and Bradshaw 2019).

Media Ownership and the Construction of Ideological Hegemony

Starting from the mid-2000s, changes in media ownership in Turkiye have served to strengthen the ideological hegemony of the political regime. The sale of Doğan Media to Demirören Group, financed by the state bank Ziraat Bank, is a clear example of the media’s economic dependence and political control (Yeşil, 2016). This change can also be explained using Antonio Gramsci’s concept of “hegemonic power” — consolidating power not only through coercion but also by controlling public opinion (Gramsci 1971).

Alternative media outlets operate under low budgets and constant judicial pressure. This situation not only marginalizes independent information sources but also fully incorporates public discourse under government hegemony.

These developments show that in Turkiye, not only the political regime but also political identity and ideology have been transformed. This system is not merely called a “presidential system,” but Erdoganism—a centralized power model where one person, one ideology, and one worldview are fused with the state.

In such a regime, the opposition is no longer seen as a political alternative but as a threat; the law speaks the language of power, not justice; and instead of citizens, subjects are created.

By 2025, Turkiye has drifted far from classical democracy. On paper, it may still appear to be a republic where elections are held, parliament exists, and the judiciary appears independent. However, in reality, none of these structures retain their democratic functionality or balancing power. Under Erdogan’s leadership, Turkiye has been dragged into institutional authoritarianism over the years, and this transformation has been carried out quietly but consistently—through “democratic procedures.”

Although this regime change occurred under a state of emergency, it did not happen through military coups but rather through procedures such as ballot boxes, referenda, and constitutional amendments. While this gave the appearance of being “legitimate” or “temporary” to many observers and citizens at first, it gradually led to the systematic dismantling of democratic values.

The Arrest of İmamoğlu and the 2025 Istanbul Metropolitan Operation: The Next Phase of Competitive Authoritarianism

The legal operations initiated against the leadership of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (İBB) in March 2025 revealed that the authoritarian regime in Turkiye had entered a new phase—not just limiting democratic competition, but aiming to eliminate it altogether. As part of the operation, administrative and criminal investigations were launched against various municipal departments, several officials were detained, and ultimately, Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu was arrested on charges such as “corruption in public office and abuse of authority” (Human Rights Watch, World Report 2025).

İmamoğlu’s arrest shows how the regime synchronizes legal processes with political goals. This strategy aims to legally prohibit rivals from participating in elections when defeating them at the ballot box becomes impossible (Esen and Gumuscu, 2021).

These repressive operations are not aimed solely at a single leader but also serve to damage the social influence and managerial legitimacy of the Istanbul municipality. This demonstrates that the regime seeks to weaken rival actors not only in the political sphere but across all public structures (Gole, 2020). The most striking aspect is that this legal action took place against the backdrop of discussions about early elections in Turkey and after a primary was scheduled in the CHP to determine the presidential candidate.

This indicates that by arresting İmamoğlu, Erdogan aims to eliminate potential leadership from the opposition and ultimately end electoral competition in Turkiye. This shows that Turkiye has surpassed even the boundaries of competitive authoritarianism and is becoming a typical authoritarian regime in which future elections will be symbolic, and real competition will be systematically restricted under the guise of legality.

Conclusion

The political transformation that has taken place in Turkiye over the past twenty years is an example of regime change that has occurred “silently” and within legal frameworks, unlike classic models of military coups or revolutionary upheaval. This change is not merely a technical modification of the system of governance but is accompanied by a radical redesign of political culture, the legal system, the media environment, and the concept of citizenship. While the official presence of democratic institutions maintains Turkiye’s democratic appearance, in reality, these institutions have lost their functional essence and have become symbolic structures.

This transformation, carried out during the AKP’s rule and especially under Erdogan’s sole leadership, is based on autocratic consolidation under the image of democratic legitimacy. Democratic procedures such as elections and referenda have been used manipulatively to strengthen the regime. The most critical aspect of this process is that the regime has been ideologically and structurally centralized around a single person.

Turkiye has now gone beyond “illiberal democracy” or “delegative democracy” and has positioned itself at the extreme edge of hybrid regime models known as “competitive authoritarianism,” experiencing a concrete and complex evolution from “electoral authoritarianism” to full authoritarianism.

The case of Turkiye shows that when there is a gap between the form and substance of democracy, autocratization can occur even within legal frameworks. Thus, this transformation serves as an important warning and political lesson not only for Turkiye but also for other semi-democratic and transitional regimes.

References

- Müftüler-Baç, Meltem. “Turkey’s Political Reforms and the Impact of the European Union.” South European Society and Politics, vol. 10, no. 1, 2005, pp. 17–31.

- Yılmaz, Ihsan, and Gülayhan Bashirov. “The AKP, the Gulen and the Judiciary: Authoritarian Politics in Turkey.” Middle East Critique, vol. 31, no. 2, 2022.

- Recep Tayyip Erdogan: "Demokrasi bizim için amaç değil araçtır." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qY52kEMQyBA

- Linz, Juan J., and Alfred Stepan. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- McCoy, Jennifer, Tahmina Rahman, and Murat Somer. “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy.” The American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 62, no. 1, 2018, pp. 16–42.

- Yavuz, M. Hakan. Secularism and Muslim Democracy in Turkey. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Taş, Hakkı. “Turkey–from Tutelary to Delegative Democracy.” Third World Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4, 2015, pp. 776–791.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. Verso, 1985.

- Gürsoy, Yaprak.“Turkish Political Culture and the Rise of the AKP.” Middle East Critique, vol. 26, no. 2, 2017, pp. 145–160.

- Es, Murat. “Authoritarian Legalism and the Transformation of the Turkish Judiciary.” Law and Society Review, vol. 54, no. 2, 2020, pp. 405–432.

- Freedom House.n Freedom in the World 2023: Turkey. https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkey/freedom-world/2023

- Amnesty International. Turkey: Annual Report 2022. https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/europe-and-central-asia/turkey/report-turkey/.

- Tugal, Cihan. The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism. Verso, 2016.

- Schmitt, Carl. The Concept of the Political. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. Crown Publishing Group, 2018.

- Gürsoy, Y.(2012). The Role of the Military in Turkish Politics: To Guard Whom and From What? European Journal of Turkish Studies, 14.

- Rabasa, A. & Benard, C. (2004). Civil Democratic Islam: Partners, Resources, and Strategies. RAND Corporation.

- Jenkins, G. (2009). Between Fact and Fantasy: Turkey’s Ergenekon Investigation. Silk Road Paper, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute.

- BİANET 2021. Tramvaydan bir an önce inme’ ihtirası. https://bianet.org/yazi/tramvaydan-bir-an-once-inme-ihtirasi-243992

- "Egemenlik Kayıtsız Şartsız Allah'ındır!" R.Tayyip Erdogan 1994 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JiPh0WmdUXs

- Tuğal, C. (2013) Passive Revolution: Absorbing the Islamic Challenge to Capitalism. Stanford University Press.

- Baykan, T. S. (2021). The Cultural Politics of Erdoganism. Turkish Studies, 22(1), 45–67.

- Taş, Hakkı. “Turkey—From Tutelary to Delegative Democracy.” Third World Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 2, 2018, pp. 195–211.

- Jenkins, Gareth. “Between Fact and Fantasy: Turkey’s Ergenekon Investigation.” Silk Road Paper, Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, 2011.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. Crown Publishing Group, 2018.

- Yabanci, Bilge. “Populism as the Problem Child of Democracy: The AKP’s Populist Re-Articulation of Religion, Nation and Democracy in Turkey.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 46, no. 3, 2019, pp. 350–368.

- European Society and Politics, vol. 22, no. 3, 2017, pp. 303–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2017.1384341

- Esen Berk and Şebnem Gümüşçü. “A Small Yes for Presidentialism: The Turkish Constitutional Referendum of April 2017.” South European Society and Politics, vol. 22, no. 3, 2017, pp. 303–326.

- Yılmaz &Bashirov, G. (2022). The AKP after 20 years: Between Islamic populism and authoritarianism. Third World Quarterly, 43(1), 186–204.

- O’Donnell, G (1994). Delegative Democracy. Journal of Democracy, 5(1), 55–69.

- Kurban, D. (2021) Limits of Supranational Justice: The European Court of Human Rights and Turkey’s Kurdish Conflict. Cambridge University Press.

- Human Rights Watch. (2022). Turkey: Events of 2022. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org

- Howard, P. N & Bradshaw, S. (2019). The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. University of Oxford.

- Yeşil, B. (2016). Media in New Turkey: The Origins of an Authoritarian Neoliberal State. University of Illinois Press.

- Gramsci, A.(1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. (Q. Hoare & G. Nowell Smith, Eds. and Trans.). International Publishers.

- Human Rights Watch. World Report 2025: Events of 2024. New York, 2025.

- Esen, Berk, and Şebnem Gümüşçü. “How Erdogan’s Populism Works: The Case of Turkey.” Government and Opposition, vol. 56, no. 2, 2021, pp. 311–333. Cambridge University Press.

- Taş, Hakkı. “Authoritarian Neoliberalism in Turkey: A New Consensus.” South European Society and Politics, vol. 23, no. 2, 2018, pp. 123–146.

Gole, Nilüfer. “Populism and the Crisis of Democracy in Turkey.” Philosophy & Social Criticism, vol. 46, no. 2, 2020, pp. 223–235.