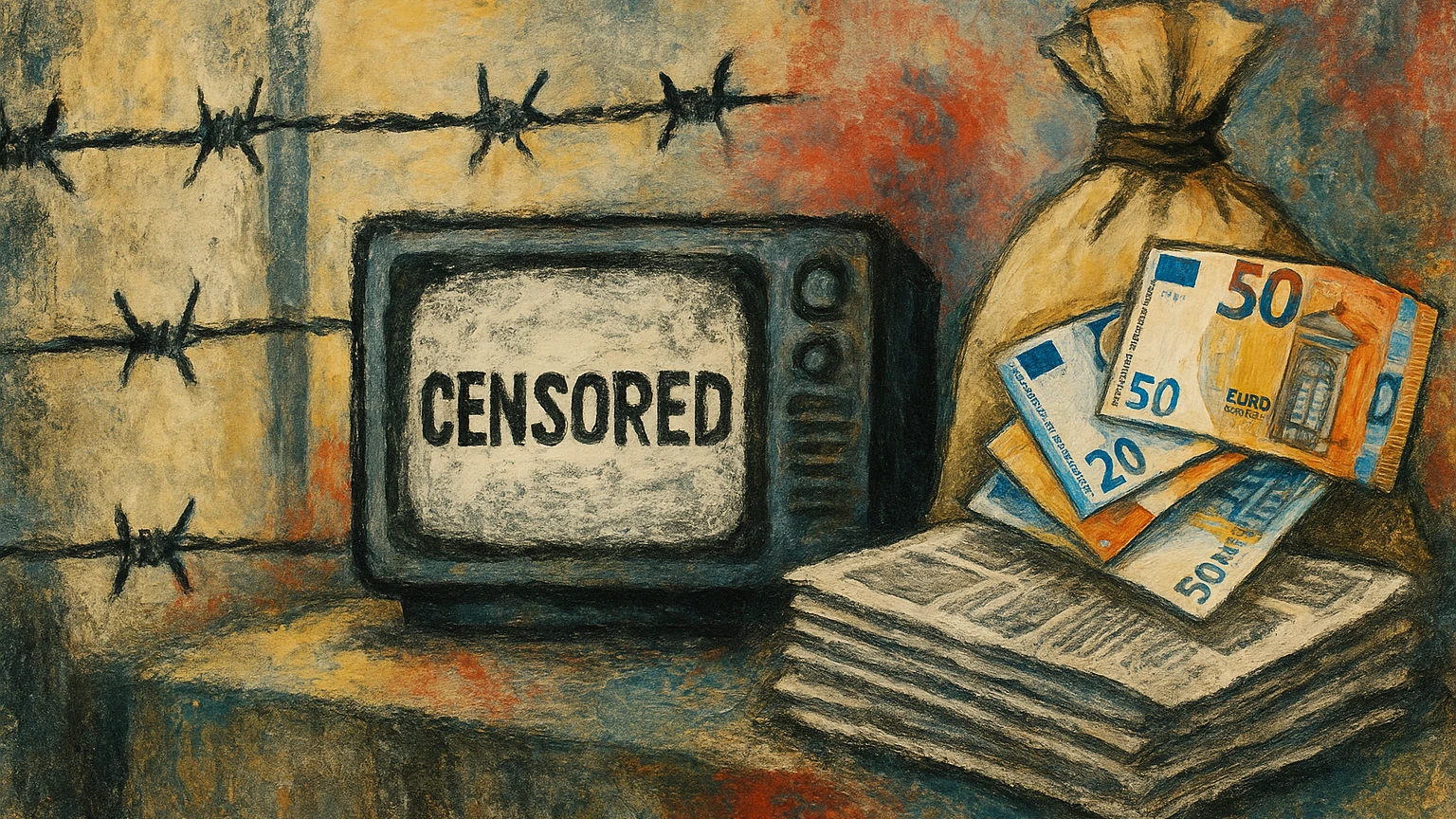

Freedom of expression and independent media are considered fundamental attributes of modern democratic societies. The ability of mass media to operate without direct or indirect pressure stimulates its essential role in shaping the political system. In democratic societies, the media plays an irreplaceable role in providing the public with professional information, exercising public oversight, and ensuring governmental accountability. However, in authoritarian or authoritarian-leaning regimes, this crucial role of the media is restricted by the administrative and law enforcement authorities in various forms. In this sense, control over the media is exercised not only through direct censorship but also through institutional mechanisms, economic instruments, administrative pressure, and selective “support” mechanisms.

Introduction

Over the past two years, under a special wave of attacks on the press, the Azerbaijani government has shut down outlets such as Abzas Media, Toplum TV, and Meydan TV, and either the majority or the entirety of their staff have been arrested (RSF, 2025). In addition, several independent journalists have been imprisoned, foreign media representatives have had their accreditations revoked, and their offices closed. Currently, around 30 journalists are in prison in Azerbaijan. As a result, the country ranks among the top five worldwide for the number of jailed journalists (Toplum TV, 2025). This process not only revives the discussion of Azerbaijan’s long-standing media problems but also makes it necessary to examine the severe condition of freedom of expression.

This analysis is structured around the research question: “Through what mechanisms does the government exercise control over the media?” amid the effective shutdown of independent media over the last two years.

The material reviews the decisive events of a process spanning more than 30 years, during which the Azerbaijani government, ignoring international and domestic protests, adopted the “Law on Media” and subsequently dealt a fatal blow to press freedom. It also examines how censorship—both formal and de facto—has been carried out since Azerbaijan regained independence, particularly from 1993 onward.

Moreover, the analysis illustrates how the government has employed various methods at different times to silence or co-opt the media and what specific outcomes were achieved in each case.

This topic is important for several reasons:

- When assessing the prospects for free media in Azerbaijan, it is vital to thoroughly study the current situation and its underlying causes and consequences.

- Revealing the synchronic connection between the deepening of authoritarianism and the suffocation of the media helps identify which authoritarian instruments must be resisted to revive a free press.

The article emphasizes that while tightening legislation, the government has also pursued a “carrot-and-stick” policy—offering housing and financial assistance to certain journalists and outlets, while at the same time imprisoning others and shutting down media organizations—to maintain psychological dominance.

The research is based on a qualitative analytical approach, referencing normative documents and international reports, and employs structural-institutional analysis to examine the mechanisms through which the Azerbaijani authorities control the media. It also draws on media reports and expert opinions.

Keywords: free media, independent media, repression, censorship, self-censorship, advertising market, authoritarianism

Limitations: The main limitation of the material is the lack of accessible electronic sources for the period prior to 2005.

Theoretical Framework

This article is developed within the framework of the theory of “Media Capture” in the context of the evolution of authoritarianism. “Media capture” is a well-established theoretical approach in the literature. In short, it is the application of the logic of “regulatory capture” to the media sector: state institutions, ruling political elites, or oligarchic groups establish systematic influence over the media through ownership structures, advertising and tender flows, legal and regulatory frameworks, oversight bodies, and editorial management, thereby “capturing” the media agenda in their favor. This process goes beyond classical censorship; through cooptation, economic dependence, and selective legal pressure, it institutionalizes self-censorship (Anya Schiffrin, 2017).

Legal and Institutional Regulation of the Press in Azerbaijan: From Freedom to Control (1992–2021)

The 1992 Law on Mass Media served for a time as the main legal act regulating press activity in Azerbaijan (E-qanun, July 1992). Remaining in force until 1999, the law was increasingly seen as incompatible with the government’s interests, prompting a series of restrictive amendments. While independent experts evaluated the law positively, government representatives repeatedly criticized it, arguing that it needed to be replaced. As a result, a new Law on Mass Media was adopted in 1999 (ICT, December 1999a).

What was the difference between these two laws? The 1992 law, passed under the Azerbaijan Popular Front (AXC) government, was one of the rare liberal examples in the post-Soviet space. It minimized state interference in media activities and allowed citizens and associations to freely establish newspapers, journals, and news agencies. In contrast, the 1999 law introduced broad and vague concepts such as “state secrets,” “extremism,” and “offenses against national and religious values,” restricting media activity. It also complicated the process of founding media outlets, introducing mandatory state registration with the Ministry of Justice—thus giving the government the power to intervene and limit media operations. Whereas the 1992 law explicitly restricted state interference in the press, the 1999 version legitimized the state’s “support and oversight” functions. Consequently, instead of fostering press freedom, the new law became a normative legal basis for restricting it (ICT, December 1999b).

The government did not stop there; it developed external mechanisms to further narrow the boundaries of press freedom, effectively testing the public’s and media’s adaptability to stricter regulation. One such mechanism was the continuation of official censorship—a remnant from the Soviet period—that persisted until 1998. Although the term “censorship” was not officially used, the function was carried out by an agency called the Main Department for the Protection of State Secrets in the Press under the Cabinet of Ministers.

During the one-year AXC rule, censorship was practically inactive, reintroduced only briefly under wartime conditions. However, when Heydar Aliyev came to power, censorship was reinstated (Refworld, 1998). Under the pretext of wartime necessity, critical materials contrary to government interests were censored without explanation—hundreds of such articles were removed from dozens of newspapers (CPJ, 1998). Although the law formally granted journalists professional freedom, in practice, censors edited or cut their materials. Despite public debate, censorship continued until 1998, when Heydar Aliyev officially abolished the Main Department for the Protection of State Secrets in the Press (Aliyev Heritage, 2010).

However, this move was soon replaced by another restrictive law—the Law on State Secrets (E-qanun, November 1996)—which became the new “Sword of Damocles” over the press. Although adopted in 1996, the law gained prominence only after censorship was abolished. Essentially, the same “state secrets” mechanism continued under a different name. The law’s vague and complex provisions allowed the government to target any media outlet or journalist at will.

Preparing to join the Council of Europe, Azerbaijan committed to reforms in human rights, the judiciary, and media between 1997 and 2001, and thus formally abolished censorship (PACE, 2000). Yet, this was only a symbolic gesture; censorship was merely replaced by legal self-censorship under the Law on State Secrets. Now, journalists were not having their articles cut, but the threat of prosecution compelled them to self-censor.

On January 25, 2001, Azerbaijan became a full member of the Council of Europe (CoE, 2001). Thereafter, normative pressure on the media partially eased. Nevertheless, the Editors’ Union—an informal but influential association of independent press leaders—worried the authorities. This body convened during crises, discussed the state of the media, raised issues before the government, and organized protests (Radio Liberty, 2007). The Editors’ Union, which did not include pro-government media leaders, continued operating until 2008.

In response, from early 2003 the government floated the idea of a Press Council. Debates began over how this body would function and whether it would ease the situation for the press. In March 2003, the founding congress of the Press Council (PC) was held (Fakt Yoxla, 2022). The Council’s first initiative was to draft a journalistic code of ethics. However, this non-governmental organization soon turned into a kind of media police. In many disputes, PC decisions rather than the Law on Mass Media became decisive. The Council failed to improve journalistic conditions and instead either supported or silently endorsed the government’s repressive policies, provoking resentment among independent media (Radio Liberty, 2008).

By creating the PC, the government neutralized the compact and independent Editors’ Union, while using the PC to tighten control more effectively. However, with time, the Press Council appeared powerless against the rise of electronic media. This was partly due to its lack of credibility as a civic institution and partly because the government preferred to strangle media freedom directly through legal mechanisms.

During the 44-day war in 2020, authorities effectively reintroduced censorship, testing the feasibility of stricter standards. Subsequently, in 2021, a draft of the new Law on Media was introduced. Public discussions followed, but the government justified the reform by claiming that despite 79 amendments, the existing Law on Mass Media no longer met “new challenges” (APA, 2021). International organizations, notably the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission, gave negative opinions (Voice of America, 2022). Independent journalists—many of whom are now either imprisoned or in exile—protested the bill outside parliament (Meydan TV, 2021). Despite all criticisms and protests, the government secured another regressive victory by adopting the law.

The New Law: Restrictions and Criticism

According to experts who compared the new Law on Media with the previous Law on Mass Media, the new act contains dozens of provisions sufficient to shut down any media outlet (Teref, 2021). The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission paid special attention to Article 26 of the law, noting that it should:

- Abolish Article 26, which imposes broad restrictions on the establishment of media, foreign ownership, and foreign financing;

- Eliminate the Media Registry or the excessive conditions required for registration;

- Remove accreditation requirements;

- Align content restrictions with Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights;

- Amend provisions related to the protection of journalistic sources;

- Clarify that platform broadcasters, on-demand service providers, and platform operators are not subject to licensing, but only to registration;

- Specify that the requirement to notify authorities before publishing or distributing printed and online media is purely informational (Caucasus Watch, 2022).

As can be seen, the Venice Commission focused mainly on two issues—media ownership and operational freedom. The law demonstrates that institutional and normative control over the media has now been fully consolidated. The government drafted the law in such a way that anyone it disapproves of can be legally prevented from engaging in journalism, or restricted at any time. Symbolically, the word “freedom” appears only once in the text of the law, whereas the term “executive power” appears 89 times—underscoring the triumph of executive authority over media independence.

Thus, it becomes evident that the government employs both legal and institutional means to establish complete control over the media—effectively “capturing” it. To this end, it changes or creates new laws as needed. This strategy aligns perfectly with the “Media Capture” theory, which posits that capture occurs when governments or politically connected networks establish direct or indirect control over media outlets to influence their agendas and content (Anya Schiffrin, 2021).

The chronology presented above highlights two main patterns:

- Strategic Legal Restriction: The government systematically reduces media freedom through legislation, narrowing the scope step by step. Its pace depends on both domestic conditions and its relations with international organizations—tightening control whenever the environment allows.

- Institutional Pressure: In parallel with legislative action, the government strengthens institutional control tools such as the Press Council and the Media Development Agency. These bodies, formed under the new legal regime, are designed to suffocate the media under stricter criteria.

Ultimately, all legal and structural mechanisms serve one purpose: to reassert full control over media content.

The Dual Strategy of Repression and Cooptation: The Formation of Journalist Imprisonment and Inducement Mechanisms as Tools of Authoritarian Control in Azerbaijan

Threats—Violence, Torture, Intimidation. In regimes dominated by competitive authoritarian systems, independent media are forced to operate under constant pressure. In fully authoritarian regimes, the media are either entirely state-owned, placed under strict censorship, or subjected to systematic repression. Major television and radio stations are controlled by the government (or its close allies), and large independent newspapers and journals may be banned by law… Journalists who incur the wrath of the authorities may face arrest, deportation, and even the risk of assassination (Levitsky & Way 2010).

Although in the early years of independence there were no recorded instances of intensive physical violence against the press in Azerbaijan, the beating of well-known journalist Zərdüşt Əlizadə by the country’s Minister of Internal Affairs during the AXC (APF) government remains a striking fact (CPJ, 1998). However, after Heydar Aliyev came to power, violence began to turn into a purposeful policy. One of the most notable incidents was the beating of Ekho-Zerkalo newspaper reporter Kamal Ali. While conducting an interview in front of the Milli Majlis (parliament) building, Kamal Ali was attacked by a security guard because, according to the guard, the interview “took too long” (Refworld, 1998). Another specific method of pressure was restricting journalists’ freedom of movement within the country. An example is the case of Azadlıq newspaper reporter Elçin Selcuk, who was detained at the airport on his way to Nakhchivan and was not allowed to enter Nakhchivan (CPJ, 1998).

After the abolition of censorship, a marked increase in physical violence was observed. To prevent the publication of articles deemed politically inconvenient or undesirable, their authors were targeted. The aim was to create an atmosphere of fear and to induce self-censorship. For instance, Zamin Hacı, who criticized Heydar Aliyev in a satirical genre in Azadlıq newspaper, was attacked by unknown persons on a dark street while walking home from work in the evening and suffered blunt-force blows to the head (CoE, 2001). After this, Zamin Hacı held a briefing and announced that he would no longer write about Heydar Aliyev. Following the incident, open criticism of Heydar Aliyev decreased.

The Murder of Elmar Huseynov. In March 2005, Elmar Huseynov, a fierce critic of the authorities and the editor-in-chief of the Russian-language magazine Monitor, was shot dead at the entrance to his home (OSCE, 2005). His killing was interpreted as a message to journalists who wrote about the ruling family. Huseynov’s articles targeted the ruling family and corruption within their activities. Moreover, Huseynov, known for his harsh style, emboldened others.

The Case of Bahaddin Heziyev. In May 2006, just 14 months after Huseynov’s murder, Bahaddin Heziyev, editor-in-chief of the independent newspaper Bizim yol, was stopped by unknown individuals while driving home late at night from work, taken to the outskirts of the city, and left in a near-fatal state. The assailants reportedly drove a car over him several times (Radio Liberty, 2006). It was said that he became a victim because of his writings on the corrupt activities of the government, particularly regarding events surrounding the export of black caviar. Having survived by chance, Heziyev underwent lengthy treatment, and after partially recovering and resuming his work, he began to attract attention for his loyalty to the authorities. In 2025, among those awarded by President Ilham Aliyev on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the press in Azerbaijan was Bahaddin Heziyev (Bizim Yol, 2025).

After the formal abolition of censorship, the methods devised by the authorities to implement it de facto were, of course, not limited to adopting new laws or amending existing ones. The facts presented above allow us to conclude that the authorities turned physical violence, murder, and torture into tools for this purpose. In this way, the government sends a message to the journalist that, if the law does not punish him, unknown persons who appear under cover of darkness can kill or maim him. Therefore, when writing about the authorities and issues sensitive to them, the journalist must take into account what might happen to him. If he does not, he could be the regime’s next victim. The situation in the media after each of the incidents involving Zamin Hacı, Elmar Huseynov, and Bahaddin Heziyev—especially Heziyev’s loyalty to the authorities and the fact that this was rewarded at the highest level—shows that the authorities’ plan works. On the other hand, such events do not have only a daily (short-term) effect; over time, as they are discussed, they form new circles of influence. Thus, this policy acquires a permanence effect aimed at the future. If, until 2005, short-term arrests, fines, and fear-driven physical injuries were considered pressure on the media, then from 2005 onward, long-term imprisonments and unresolved deaths or attempted murders turned into psychological pressure on media freedom. In short, the government did not refrain from harsh methods for more concrete results; indeed, it decided to systematize these methods.

Economic Pressures: Closing the Advertising Market. From the second half of the 1990s, one of the most discussed issues in the country was advertising in the press. Although editors repeatedly brought this issue up for discussion, the problem could not be solved because its source lay with the authorities. On the contrary, over time it became an overt instrument of pressure against the media (IREX, 2018). One of the foundations of independent financing is, of course, the ability to receive advertising. However, independent or relatively independent legal and natural persons, as well as businesspeople, were reluctant to place advertisements in critical media. The authorities regarded such actions as indirectly financing their critics and reacted harshly. As a result, independent media could not finance themselves through advertising. Consequently, some outlets that wanted to earn income from advertising felt compelled to be loyal in order to survive.

A second key method of economic pressure was that most companies engaged in newspaper sales were under government control. Among them, “Azərmətbuat yayımı” functioned as a state body, while “Qasid” operated in a pro-government manner. The kiosks of the independent company “Qaya” were removed from the city, and mobile newspaper sales were restricted (Voice of America, 2006). The aim was to ensure that financial resources either did not reach editorial offices, or reached them late, or reached them in the amount and at the time desired by the authorities. For example, when the opposition newspaper Azadlıq was shut down, the pro-government “Qasid” company refused to pay the editorial office revenues from newspaper sales amounting to 70,000 Azerbaijani manats (Index on Censorship, 2016). This is a serious sum for media outlets that cannot earn from advertising.

Arrests and Fines. One of the longest-standing mechanisms of pressure by the authorities on independent media is the imprisonment of journalists. In Azerbaijan, since Heydar Aliyev came to power, the imprisonment of journalists has been used as a permanent pressure tactic on the media.

In June 1995, the satirical newspaper Çeşmə was among the first to be targeted. Editor-in-chief Ayaz Ahmadov and other staff members, including Yadigar Mammadli of Cümhuriyyət newspaper, were arrested on charges of insulting the honor and dignity of the president. The real reason for the arrest was the publication of a caricature of Heydar Aliyev (Amnesty International, 1995). Subsequently, at various times, the editors-in-chief and writers of Yeni Müsavat and Azadlıq were sentenced to long prison terms.

Because information about state bodies closed to the press was usually published without obtaining their comments, these agencies could easily, and by political order, sue newspapers and demand damages in amounts considerable for those outlets. For example, Azadlıq newspaper was forced to close because it could not pay the debt arising from such a court ruling (Modern, 2012). The editor-in-chief of Yeni Müsavat, meanwhile, became “reformed” to the extent of being decorated by Ilham Aliyev (Musavat, 2024).

Inducement Methods: Apartments for Journalists, Money for Media Outlets, and Individual Incentives

On the one hand, the authorities imprison journalists, fine editorial offices, and shut down outlets; on the other hand, they openly seek to co-opt editorial offices and journalists through methods that clearly contradict international professional ethics, offering official support amounting to bribery. And naturally, they set their own conditions when granting this support. The Fund for the Support of Mass Media under the Presidential Administration, established for this purpose, engaged in open bargaining. Providing apartments to journalists was considered the main reward for loyalty. It even emerged that after the apartments were awarded, utility payments were collected from journalists by this organization (Ayna, 2019). Editorial offices were granted monthly financial support under various “project” labels. For outlets that accepted this support but continued to criticize the authorities, funding was soon cut. Not content with this, the Fund organized article contests on topics promoting the political leadership and promised high fees to the winners. Thus, individual “initiatives” that could not withstand competition in the media marketplace were given room to flourish. Such articles usually “researched” the “legacy” of Heydar Aliyev and linked it to the policies of Ilham Aliyev (Yeni Azərbaycan, 2020).

Control over Content as an Authoritarian Strategy

Looking at the path traversed by the Azerbaijani media as the authoritarian system perfected itself, the factual record reveals an important underlying thread. The system’s struggle is not about whether newspapers exist or not, or whether websites function or not. The government directs all its efforts—by both direct and indirect means—toward seizing control over media content. When it cannot completely neutralize a media outlet, it targets, co-opts, or intimidates specific individuals, and so on. All this is to dominate content: first to achieve a softening of criticism, and then to eliminate it entirely, ensuring the production of articles and topics favorable to the authorities.

Why is this so important? The political essence of freedom of expression lies in its discursive nature—unhindered, reciprocal expression. For a self-reinforcing authoritarian system, this poses a serious threat. Free discussion means competition of ideas and the circulation of information; in other words, it is the basis of political competition. This is inversely proportional to the rules by which authoritarian governance sustains itself. The war against free media content is a matter of life and death for authoritarianism. The most acute period of this war up to 2023—comprising arrests and economic pressure overall (2014–2016)—can be considered the collapse period of Azerbaijan’s traditional media. With the closure of the Azadlıq newspaper, the shutdown of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Baku bureau, the arrests of journalists Khadija Ismayil and Seymur Hezi, the mass emigration of journalists, and the de facto alignment of Yeni Müsavat with the government camp, this process concluded. Thus, for a time, the authorities considered their job with the free press done. With a few minor exceptions, the government took control of media content domestically.

The Crisis of Authoritarian Control in the Digital Space: The Rise and Repression of a New Generation of Independent Media in Azerbaijan (2015–2024)

At a time when the Azerbaijani authorities had fully neutralized traditional media, Meydan TV, which published content solely on internet platforms and social networks, began operating; a few years later, Abzas Media and Toplum TV also achieved significant success. Professional journalistic teams revived the media and political scene with content broadcast on YouTube, Facebook, and other social networks. Although all three media outlets tried to cover all topics, a certain specificity emerged in their activities. Meydan TV gave greater priority to social content and gained popularity in this direction. Abzas Media drew attention with its anti-corruption investigations and came under government attack precisely for this activity. Toplum TV broke the political silence with its morning and evening live broadcasts, analytical programs, and debates. Debates between government representatives and independent/opposition politicians and civil society activists sparked discussions across the country and increased civic engagement. This once again raised questions for the regime’s authoritarian essence. These organizations, functioning more as platform broadcasters than as classical media, brought the “content problem” back to the agenda. The plan to silence society and gain total control over content was clearly disrupted, and the control mechanisms the regime had built for deepening and prolonging authoritarianism failed to work. Legal and administrative frameworks such as the Law on Media and the Media Development Agency could not suffocate these outlets. The authorities faced a new situation. Therefore, the only recourse left was to rely on law enforcement agencies. For this purpose, in November 2023, the government launched a wave of arrests against Abzas Media (Pravda, 2023). First, the director of the outlet, Ulvi Hasanli, then editor-in-chief Sevinc Vagifgizi, and later staff members Elnara Gasimova and Nargiz Absalamova were arrested. Subsequently, in March 2024, an operation was initiated against Toplum TV: the editorial office was raided by police, a search was conducted, all employees present were taken to the Baku City Main Police Department, and the office was sealed (Abzas, 2024). Akif Qurbanov, Ruslan Izzatli, Alesger Mammadli, Ali Zeynalov, Mushfiq Jabbarov, Ramil Babayev, Ilkin Emrahov, and Farid Ismayilov were arrested. In the next wave of arrests at the end of 2024, Meydan TV’s employees were targeted: Aynur Elgunesh, Natig Javadli, Ramin Deko (Jabrayilzade), Aytaj Tapdiq, Khayala Aghayeva, Aysel Umudova, Fatima Movlamli, Ulvi Tahirov, and Ahmad Mukhtar were arrested. At the time this material was prepared, the Abzas Media team had been sent to penal institutions with harsh sentences of 7, 9, and 10 years handed down by a sham court; the first-instance trial in the Toplum TV case was ongoing; and the investigation in the Meydan TV case had still not been completed.

A Necessary Aside. There are striking arrests in both the Abzas Media and Meydan TV cases. For example, Ulviyya Ali, who works independently for Voice of America, and Shamshad Aga, editor-in-chief of the website Argument.az, were arrested in connection with the “Meydan case,” while Farid Mehralizade, an independent expert for Radio Liberty, was arrested in connection with the “Abzas Media case.” The reason for all three arrests was that these individuals produced independent content. Because they stood out individually, the government’s investigative strategy was simply to attach them to separate “cases.” This once again proves that the most important factor for the current regime is the issue of independent content, and that all these arrests and control tools are for this reason.

Conclusion

Both the factual record presented and the analytical conclusions show that the self-reinforcing political authoritarianism in Azerbaijan primarily aims to control media content. To this end, it applies several methods in hybrid fashion. For example, at the same time it rewards one editorial office and fines another. It makes one journalist a winner in a contest promoting the government and arrests or tortures another. It closes the advertising market, prevents revenue from sales from reaching editorial offices, and on the other hand creates the KİVDF (Mass Media Support Fund) to organize funding competitions. A second key conclusion is that the government does not treat this process as a series of isolated incidents or occasional actions tied to specific moments in time. On the contrary, control over the media is a systematic, purposeful, and organically daily process that perfects itself. The parallel and permanent use of inducement methods alongside arrests, torture, and threats is clear proof of this. In parallel, by creating new laws or legal instruments in different periods, it has continued to constantly update its normative mechanisms and to squeeze the media through these means. In other words, the Azerbaijani authorities have followed a typical authoritarian path to seize full control over the media.

Recommendations

Reviewing the current situation and the process up to this point, we can say that a number of steps are essential for the resuscitation of free media by domestic and international actors:

- Media outlets that continue their work, even with very limited means, should be supported;

- It must not be allowed for the authorities to close all windows; efforts should be made to launch new initiatives, or such efforts should be supported;

- International organizations and governments that believe in the importance of human rights should keep this issue in focus. Otherwise, the macro environment that is closing may close completely;

- Platforms should be established abroad to cover topics prepared in Azerbaijan in various areas, thereby demonstrating that the purpose of the ongoing repression has not been achieved;

- Solidarity should be achieved among independent news and content producers—excluding disinformation producers—which is of great moral and political significance.

Finally, this material concludes that the process of exercising control over the media in Azerbaijan is directly proportional to the exercise of control over the judiciary, the economy, and the market. Therefore, new research and approaches must be comprehensive to resolve the problem; these areas should be studied together. Issues of freedom of expression, a free market, and an independent judiciary must be addressed in an integrated manner, because the absence of any one of these elements creates risks for the existence of the other two.

References:

RSF, 2025 Flood them with fans

https://rsf.org/en/flood-them-fans-rsf-launches-solidarity-campaign-together-exiled-azerbaijani-organizations

Toplum tv, 2025 Azərbaycan jurnalist həbsinə görə ilk 5 ölkə arasındadır – İFJ

Anya Schiffrin, 2017. Media Capture and theThreat to Democracy. https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/CIMA_MediaCaptureBook_F1.pdf

E-qanun, İyul, 1992 “ KİV Haqqında Azərbaycan respublikasının qanunu”

https://e-qanun.az/framework/7512

İCT, Dekabr 1999 a. KİV Haqqında Azərbaycan respublikasının qanunu

İCT, Dekabr, 1999 b KİV Haqqında Azərbaycan respublikasının qanunu

Refworld, 1998 Mixed Signals: Press freedom in Armenia and Azerbaijan https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/cpj/1998/en/56344

CPJ, 1998 Censorship While You Wait: An Azerbaijani Newspaper Struggles to Stay Alive

https://cpj.org/reports/1998/03/caucasus-page7-15/?utm_

Aliyev-heritage, 2010 Heydar Aliyev Heritage Research Center Publications

https://aliyev-heritage.org/en/78817400.html

E-qanun, Noyabr, 1996 “Dövlət Sirri Haqqında Azərbaycan Respublikasının qanunu”

https://e-qanun.az/framework/3731

PACE, 2000 Azerbaijan’s application for membership of the Council of Europe

https://pace.coe.int/en/files/16816/html

COE 2001 Azerbaijan // 46 States, one Europe

https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/azerbaijan

Azadlıq radiosu, 2007 Redaktorlar piketi təxirə saldılar

https://www.azadliq.org/a/397178.html

Fakt Yoxla, 2022 Was the Press Council established in Azerbaijan for the first time in the CIS?

https://www.faktyoxla.info/en/media/was-the-press-council-established-in-azerbaijan-for-the-first-time-in-the-cis

Azadlıq Radiosu, 2008 Heç kim Mətbuat Şurasının fəaliyyətindən razı qala bilməz

https://www.azadliq.org/a/435591.html

APA, 2021 79 dəfə dəyişdirilən "KİV haqqında" qanun müasir çağırışlarla uzlaşmır

https://apa.az/media/79-defe-deyisdirilen-kiv-haqqinda-qanun-muasir-cagirislarla-uzlasmir-675064

Amerikanın səsi, 2022 Venesiya Komissiyası: “Media haqqında” qanunun bir sıra maddələri ifadə və media azadlığı ilə bağlı Avropa standartlarına uyğun deyil

https://www.amerikaninsesi.org/a/6624869.html

Meydan tv, 2021, Jurnalistlər Milli Məclisin qarşısında yeni media qanun layihəsinə etiraz edirlər

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn_-Nr7hiCo

Tərəf, 2021 Media eksperti iki qanunu müqayisə etdi: oxşarlıq yoxdur, təzad var

Caucasuswatch, 2022 Venice Commission criticizes new Media Law in Azerbaijan

Anya Schiffrin, 2021 Media Capture: How Money, Digital Platforms, and Governments Control the News. s. 3.

Levitsky & Way 2010 Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. s 5

CPJ, 1998 Censorship While You Wait: An Azerbaijani Newspaper Struggles to Stay Alive

https://cpj.org/reports/1998/03/caucasus-page7-15/

Refworld, 1998 Mixed Signals: Press freedom in Armenia and Azerbaijan

https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/cpj/1998/en/56344

CPJ, 1998 Cut It Out: Notes from An Azerbaijani Censor

https://cpj.org/reports/1998/03/caucasus-page6/

COE, 2001 Freedom of expression and information in the media in Europe

https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewHTML.asp?FileID=9222&lang=EN

OSCE, 2005 Murder of prominent Azerbaijani journalist appalls OSCE Office in Baku

https://www.osce.org/baku/57249

Azadlıq radiosu, 2006 Opposition Editor Beaten Up In Azerbaijan

https://www.rferl.org/a/1068514.html

Bizim Yol, 2025 Azərbaycan Respublikasının Prezidenti İlham Əliyevin fəxri diplomu laureatlara təqdim olunub

https://bizimyol.info/az/news/549046.html

İREX, 2018 Azerbaijan

www.irex.org/sites/default/files/pdf/media-sustainability-index-europe-eurasia-2018-azerbaijan.pdf?utm

Amerikanın səsi, 2006 “ Beynəlxalq Jurnalistləri Müdafiə Komitəsi Azərbaycanda mətbuat azadlığında ciddi problemlər olduğunu bildirir”

https://www.amerikaninsesi.org/a/a-56-aze-beyurtas-88604957/702110.html?utm

İndexoncensorship, 2016 Azadliq: “We are working under the dual threat of government harassment and financial insecurity”

https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/06/azerbaijan-azadliq/

Amnesty İnternational, 1995 AZERBAIJAN: UP TO SIX YEARS' IMPRISONMENT FOR "INSULTING THE PRESIDENT

https://www.amnesty.org/es/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/eur550061995en.pdf

Modern, 2012 Tağı Əhmədov “Azadlıq” qəzetini 30 min manat cərimələtdirdi

https://modern.az/tehsil/25319/tai-ehmedov-azadliq-qezetini-30-min-manat-cerimeletdirdi/

Musavat, 2024 Prezident İlham Əliyev Rauf Arifoğlunu təltif edib

https://musavat.com/mobile/news/prezident-ilham-eliyev-rauf-arifoglunu-teltif-edib-foto_1058069.html

Ayna, 2019 KİVDF böyük qalmaqal qoparıb: Bu, jurnalistləri Prezidentə qarşı qaldırmağa cəhddir

https://ayna.az/kivdf-boyuk-qalmaqal-qoparib-bu-jurnalistleri-prezidente-qarsi-qaldirmaga-cehddir

Yeni Azərbaycan, 2020 “Yeni Azərbaycan” qəzeti KİVDF-nin elan etdiyi müsabiqə üzrə növbəti onlayn “dəyirmi masa” keçirib

https://www.yeniazerbaycan.com/Sosial_e54260_az.html

Pravda, 2023 Ülvi Həsənli saxlanıldı

Abzas, 2024 “Toplum TV”-nin ofisi möhürləndi, əməkdaşları saxlanıldı

https://abzas.org/en/2024/3/toplum-tv-nin-ofisi-mohurlne7638ee5-d/